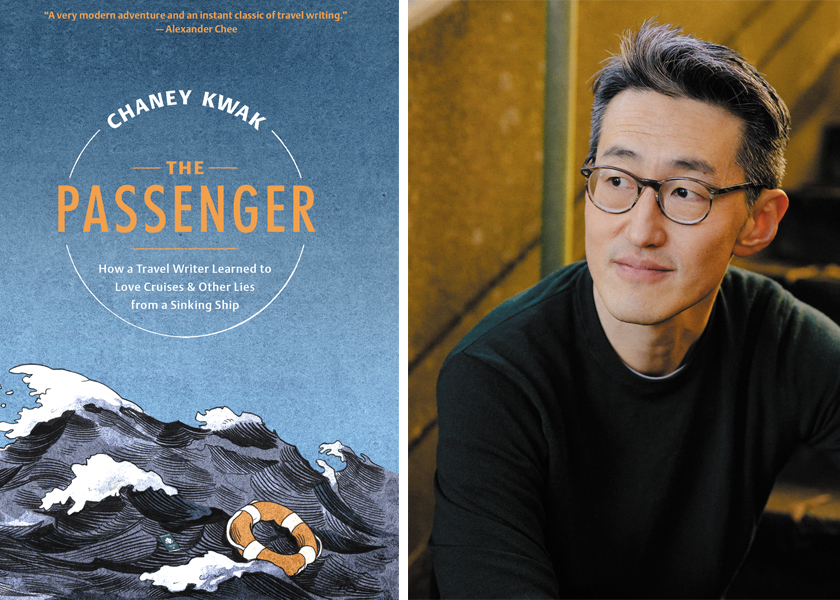

Author Interview: Memoir meets news reporting in Chaney Kwak’s premier book The Passenger | By Martha Vickery (Spring 2021 issue)

There is a moment between the thought that an accident is about to happen and the moment of impact, like the fraction of a second in mid-air after a spectacular trip over a laundry basket at the top of a stairway, or the flash of time between a swerve on a snowy road and the tumble off into a ditch, where time slows to a crawl and the mind thinks some long thoughts like “should’ve moved that laundry yesterday,” or “why did I go this way to work?”

In Chaney Kwak’s The Passenger, that in-between moment stretches into more than 24 hours as the cruise ship on which he is travelling loses its engines in stormy seas and drifts slowly toward a rocky shoal. The passengers are gathered in a central room of the vessel, avoiding the odd flying bottle or dislodged piece of furniture as they wait for evacuation by helicopter. The hours drag on.

As he waits, Kwak thinks some long thoughts, like “How did I get here?”

The result is part disaster story and part memoir (subtitled How a Travel Writer Learned to Love Cruises and Other Lies from a Sinking Ship), as Kwak tells the story of the rescue, while reflecting on travel writing, on being a son of Korean American immigrants and on letting go of a longstanding, but failing romantic relationship with a man who has been his partner since age 22.

Kwak has been a prolific travel journalist, has ghostwritten for others, contributed to others’ books over the years and produced some fictional short stories, but has never written his own book until now. The book launch is June 10 with a Minneapolis bookstore, Magers and Quinn, sponsoring a virtual launch party. Kwak lives in San Francisco, and will attend from there.

Social media is anathema to Kwak. He describes in the story his chilling revelation of how social media really operates as he searches for news online about the ongoing ship disaster he is experiencing. “I was so morbidly fascinated as well as repulsed at the rate speculation spread at the same time as actual facts,” he said. He read the words of people squabbling over what they thought must be happening, untroubled that they were broadcasting to the world information with no documentation to back it up. The lightning-fast proliferation of these lies, he said, was scary.

Lately, he has been in the self-promotion business for the new book, which requires social media savvy. To him, becoming proficient in social media has been “nerve-wracking.”

Built around the memoir component is the unfolding rescue of 1,393 people from the ship Viking Sky, which started with an engine failure on March 23, 2019, in a very unpredictable piece of water off the coast of Norway. The story comes from Kwak’s viewpoint, but with research and interviews, he also adds the point of view of the captain, the rescue guy on the helicopter, the tugboat captain who tried but could not attach to the ship for many hours, and a few crew members who, on a normal cruise, are invisible and silent.

At one point early in the disaster, there was a frightening moment when the ship almost tipped over, then righted itself, after being hit broadside by a gigantic wave. The force of the water broke through the door to the upper deck where Kwak was standing at the time, washing furniture and people around and giving him a sideways view of the horizon. It happened too fast for him to understand what was happening. Crewmen who were outside preparing lifeboats for deployment are called in. The deck was too dangerous for the crew to be working outside. Thereafter, the frightened passengers began their long wait for helicopter rescue.

The reality of an impending disaster lays waste to the façade of cruises. There are the upper decks where the magic happens, and below decks, where the real work goes on. The ship may seem luxurious, but as Kwak finds out, the side tables are stuck into the walls, and the legs are made of cheap particleboard.

“If you think about it, cruises are such a bizarre concept, right? Build a city that can float, and then go charge into these elements where humans can’t really survive. And when that surface breaches, that’s when things get super interesting,” he said.

The crew cannot be faulted, he said. They did their best to keep the façade going. “It is admirable that they were bound to that sense of duty. And also, it makes you wonder. No social hierarchy ever changed through the whole process. Even in the midst of a disaster, an old-world order remains intact.” It was, he said, a “kind of microcosm of how the world functions.”

Kwak crafts his memoir in the form of self-reflection during the 27 long hours of simply sitting around, thinking of how to go on with his life, should he survive, after such a defining event. In intervening chapters, he weaves in accounts of the rescue story as it unfolds.

The result is not only interesting journalism and sociology, but the predicament also invites some interesting dark humor. It’s a reminder how people are equal in a crisis, the low-ranking ship’s crew snapping into brand new emergency roles at the captain’s command. It is a reminder that bravery is a real thing, and there are some people who specialize in running toward disaster with little thought of their own safety. It is also a reminder about mortality; to appreciate life’s moments, because we never know when we may need to jump ship.

Kwak was driven by the desire to tell the disaster story with accuracy and integrity, particularly after suffering through so many social media nonsense accounts. “It was also really important for me to see the event from different vantage points,” he said, “and it was even more important for me to go back to people like the rescue workers, and just to see how things looked from their perspective.”

The author conducted interviews months after the event was over. Hearing experts’ opinions made him realize how close the rescue was to an all-out tragedy. A helicopter captain told him “he had never seen a ship do that —- this veteran of the Danish navy,” Kwak said. A passenger who was an early evacuee said she heard, while ashore waiting, that “authorities had said that they expected heavy casualties, due to the conditions of the sea,” he said.

As a person who is “morbidly curious, and having made a living working for newspapers and magazines, I was fascinated to get that kind of 360-degree view,” he said.

Writing the book at the outset of the pandemic, Kwak contacted former staffers of the Viking Sky who never got any credit for their heroic actions, and who suddenly had nothing to do, because all cruises were cancelled. Some, abruptly unemployed and financially strapped, even asked him about jobs, or whether they could be paid for an interview.

In the months of staying home, his own travel writing set aside due to the pandemic, Kwak worked on piecing the story together, and even writes out his thinking process, and how, in his post-disaster life, another kind of sea change is taking place. A year after the defining event he writes of how “traveling with hundreds or thousands of passengers aboard a cruise ship sounds like a relic of another era.”

Finally, he struggled with how vulnerable he should be in the memoir story, in which he reflects how to right the foundering ship of his life, and how he has been acting like a helpless passenger, not a responsible crew member with the agency to save it from disaster. In the end, he tells a lot.

In that respect, the writing of The Passenger became a “strange hybrid project,” he said. Although the memoir portion takes up less than 10 percent of the book in terms of words, it is a key component of the story. It makes it “a super-deeply personal story, with some really painful parts that I haven’t even really discussed with my own family —- like my ex’s infidelity,” he said.

The book is a debut in the sense that it is the first book wholly written by him with his name on the cover, Kwak said. “It is also a debut because it is my first book of something personal,” he said. “When you are writing travel, you get to choose how much you want to share. Certainly, I’ve written kind of personal pieces, but nothing like this level of personal, and it feels really scary,” he said. “I’ve realized it takes a lot of courage to be weak in public.” He realizes that with a book of non-fiction, what’s also bound to be critiqued “is your life itself.”

Kwak also reflects on the privilege that put him on the Viking Sky in the first place. “For me to pretend I didn’t have that kind of privilege thanks to my immigrant parents who worked so hard for that would be very disingenuous. I can’t refute that.”

He was in a small minority as a non-white passenger. The brave Tagalog-speaking Filipino crewmen who were nearly washed overboard trying to prep the lifeboats looked more like him than the passengers. “Being Korean is a really strange place because you are really neither/nor. …I’d like to think I made a lot of social observations precisely because I am not part of any group. But that can be a very lonely place as well.”

As he explored his own truth, Kwak said, the cruise became “an interesting metaphor that I never thought of —- the bubble of the relationship I was living in. Because I think we all trick ourselves into living in one. I was sort of living a cruise life, trying not to see what was happening.” In fact, the Viking Sky cruise was the second cruise he had accepted for an assignment in two months. More than a year later, he was understanding why.

“In many ways I went on that cruise trying to escape,” he said. “I thought it was going to be a fluff piece, and it ended up changing my life.”

A book launch event for The Passenger entitled Chaney Kwak in conversation with Lori Ostlund, will be held on Zoom June 10, at 7 p.m. The event is sponsored by Magers and Quinn Booksellers in Minneapolis. Lori Ostlund is an award-winning author and Minnesota native. For more info: magersandquinn.com.

Chaney Kwak has a website at: www.chaneykwak.com