Whitewashed U.S. accounts and popular films versus the real origins of the Korean War and its consequences on a generation of Koreans | By Tim Shorrock (Summer 2025)

To mark the official start of the Korean War, I go deep with the historian Bob Buzzanco on the war’s origins in the enormous divide inside Korea after it was colonized by Japan from 1910 to 1945.

To most Americans, the official date of the Korean War’s beginning is June 25, 1950, when North Korean military forces crossed the 38th parallel and “invaded” the South. To commemorate the date, I was invited to appear on the Green and Red Podcast by host Bob Buzzanco and his producer, Scott Parkin (if you just prefer to listen, click here).

Here’s how Bob introduces the show:

It’s the 75th anniversary of the Korean War. Looking at the politics and history of the “Forgotten War,” we talk with journalist Tim Shorrock. We discuss the Open Door in Asia [during the late 1800s and early 20th century], the Japanese occupation of Korea, communist resistance to it, the rise of right wing South Korean forces, North Korea crossing the 38th parallel, the Cold War and more.

It was an excellent show, in part because of the probing questions from my hosts, and we go back all the way to the late 1800s, during the era of the Joseon Kingdom in Korea and its desperate attempt to keep the U.S., Japan, Russia, and the other imperialist powers out of the peninsula.

You will notice that I put the term “invaded” above in quotes. I do that because the so-called “Forgotten War” was in reality a civil war that began almost from the moment that the U.S. unilaterally divided the Korean Peninsula in two after dropping its second atomic bomb on Nagasaki. The Soviet Union quickly agreed to the proposal, and by early September, the U.S. Army had occupied the southern half with its troops.

Stalin’s Red Army, which was already in Korea by then, occupied the northern half, which shares a short border with Russia. By the summer of 1950, the U.S. and Soviet troops had withdrawn, leaving the two separate states in the once-unified country to fight it out. South Korean leader Syngman Rhee had threatened for months to “march north” and “liberate” the DPRK. But to the shock of his divided government and the U.S., which still had 500 military advisers in country, the DPRK crossed the line first in an attempt to overthrow Rhee and kick U.S. forces off the Korean Peninsula.

It was a desperate gamble on the part of Il Sung Kim, the DPRK leader who fought the Japanese throughout World War II in Manchuria. Noting that the U.S. had not intervened to prevent China’s communist revolution in 1949, he believed the Truman administration would stay out of Korea too. But he was dead wrong, as he quickly learned when President Truman, with Republican taunts of “who lost China?” ringing in his ears, ordered hundreds of thousands of American soldiers to the Korean front.

I’ve always wondered: how can we call Kim’s action an “invasion” when his army was one faction of Koreans fighting another across a temporary border that had been imposed on them by two powerful foreign nations? The truth is, we can’t. That so-called border was completely arbitrary and had nothing to do with the reality of Korea.

As I write in my story The Nagasaki Bomb and the Division of Korea about the U.S. decision to draw the line, “Not a single Korean was consulted, leaving this proud country with a 5,000-year history as a single nation out in the cold for this momentous decision.” Eighty years later, Korea remains bitterly divided and is still in a technical state of war.

In the book I’m writing about U.S. intervention in Japan and Korea after World War II, I make three key points about the war that I also discussed in the show.

- The all-out war between the U.S.-controlled UN forces and the North Korean Army that began in June 1950 was preceded by a vicious U.S.-led counterinsurgency war in the South against leftist anticolonial forces that killed thousands of people long before the “invasion” from the North.

By 1946, the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea and Syngman Rhee, a U.S.-educated independence activist, had created a South Korean state led by landlords, businessmen, right-wing nationalists and anti-communists. Many of them had collaborated with the Japanese during its 35 years of colonial rule. Their policies, dictated by the U.S. military, triggered a massive political struggle with the anticolonial and powerful South Korean left, which was demanding full independence and a single, unified Korean government.

The counterinsurgency campaign culminated on the island of Jeju, where the U.S.-led South Korean army crushed an uprising in the only province to vote against Rhee’s plan to create a separate state in South Korea (that atrocity is the subject of Nobel laureate Han Kang‘s latest novel, We Do Not Part). The internal struggle inside Korea caused over 100,000 deaths before the North Koreans crossed the demarcation line in June 1950, according to a senior U.S. diplomat who was stationed in Seoul during that time.

I conclude in my book that the people of southern Korea were the first to be subjected to the anti-communist death-squad repression chillingly described as the “Jakarta Method” by the journalist Vincent Bevins in his great book, Washington’s Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped our World.

- The war took place just as the “reverse course” in the U.S. occupation of Japan was coming to fruition. The shift from democratization to remilitarization greatly profited Japan, which saw its economy grow by leaps and bounds when the U.S. flooded Japanese industry with procurement orders to help it fight the unfolding war in Korea.

The change in U.S. policy towards Japan began in the late 1940s, when the U.S. government, backed by a powerful coalition of American conservatives and businessmen with close ties to the Japanese elite, shifted its focus from democratizing and demilitarizing Japan to making the country the linchpin for the U.S. Cold War strategy in the Far East.

Almost overnight, U.S. policy shifted from punishing Japanese officials and industrialists responsible for World War II to enlisting them in a global war against the Soviet Union and China. Meanwhile, in a massive “red purge,” Japanese communists and radicals who had been freed from Japanese prisons in the initial days of the occupation were forced out of public life and thrown back in jail. Then, with Japan in deep recession, the Korean War began, and the country’s economy was saved.

Not only did Japan provide the bases the U.S. Air Force used to pummel Korea, but its industries supplied most of the jeeps, radios, and weapons used by the U.S. military in its fight to eradicate the communist threat. This is how the State Department described the economic transition in an official history that has remained on the web until 2009:

In 1950, “the most serious problem [in Japan] was the shortage of raw materials required to feed Japanese industries and markets for finished goods. The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 provided [U.S. Occupation forces] with just the opportunity it needed to address this problem, prompting some occupation officials to suggest that, “Korea came along and saved us.” After the UN (sic) entered the Korean War, Japan became the principal supply depot for [the U.S.-commanded] UN forces.

That’s quite a claim: A terrible war next door “saved” Japan and the U.S. occupation. In fact, the amount of procurements purchased by the Pentagon in Japan from 1950 to 1953 so rejuvenated its economy that historians there still call it the “Korean War boom.” As Chalmers Johnson, the late, great historian of postwar Japan often noted, the U.S. military spending during this period replicated in Japan what the Marshall Plan did in Europe.

The Korean War also laid the seeds for Japan’s remilitarization. At the outset of the fighting, with U.S. forces in Japan suddenly deployed to Korea, Gen. Douglas MacArthur ordered the Japanese government to establish a national police force. Despite the public support for the constitutional prohibition against a standing army, this force became the nucleus of Japan’s new “Self Defense Forces” that is today one of the largest militaries in the world.

The “reverse course” continued through the Korean War, which the U.S. used in 1951 as leverage to force Japan to sign a peace agreement that guaranteed the permanent stationing of U.S. bases on Japanese soil. Since 1955, Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party, created with the financial backing of the CIA, has been America’s closest and most subservient ally in Asia.

- Truman’s intervention in Korea transformed the civil war into a global struggle that almost triggered World War III. That happened when his administration (not Gen. MacArthur, as most U.S. historians claim) ordered the U.S.-led UN and South Korean forces to cross the 38th parallel and try to overthrow the North Korean State.

If the U.S.-run UN forces had stopped at the original border, Truman might have deserved credit for “saving” South Korea. But Cold War hubris got in the way. After MacArthur led the counterattack in his Inchon invasion, the administration sent U.S. and South Korean forces deep into North Korea in a brazen attempt to “roll back” communism and establish a permanent strategic beachhead on Korea’s borders with China and the USSR.

This sparked the Chinese intervention that sent the U.S. Marines, and the UN army back into South Korea. Millions died in one of the bloodiest conflicts of the 20th century. Most of those deaths came at the hands of the U.S., which – as President Trump boasted about the U.S. Air Force over Iran last week – seized control of Korea’s skies in the first days of the war.

As Korean American writer Grace Cho wrote in an excellent article in The Nation, “When we say ‘war,’ maybe what we really mean is ‘genocide.’” That’s exactly what it was.

Why the Korean War is not forgotten in Korea

During the Korean War, over three million Koreans were killed, the majority of them civilians. Nearly 40,000 Americans, about 4,000 foreign troops in the U.S.-run UN Command, and over 100,000 Chinese also died. Millions of Koreans were left homeless, their lives forever scarred by the fratricidal violence. Afterward, the entire country was left in cinders; in the North, every single city was destroyed.

Much of that destruction was caused by the U.S. Air Force, which wrested control of the skies early on and spent the war bombing, strafing, and splashing napalm everywhere it could find the communist enemy. In November, 1950, after China’s intervention in the battle shortened MacArthur’s vision on a short war in which the boys “would be home by Christmas,” the arrogant commander pronounced a death sentence on huge numbers of Koreans with a scorched-earth policy.

“Every installation, facility, and village in North Korea now becomes a military and tactical target,” he ordered. That inhumane directive was gleefully carried out by Gen.Curtis LeMay, the Air Force Chief of Staff who masterminded the firebombing of Japan just five years before. “Over a period of three years or so,” he said in an oral history for Princeton University, “we burned down every town in North Korea and South Korea too,” adding that “a lot of people can’t stomach it.”

The genocidal nature of the war was carefully hidden from the American people by Hollywood, which produced dozens of movies that were sheer propaganda and served to cover up U.S. war crimes. “When the war erupted in June 1950, Hollywood was still busy cranking out World War II epics,” the reporter Ki-Hoon Moon wrote in a brilliant article in The Korea Herald on June 24.

That conflict had a clear narrative arc: good versus evil, and a victory that made all the sacrifice feel earned. Korea, by contrast, offered no such closure — no victory to justify suffering, no heroes to welcome home. What eventually took shape was a cinematic trend scholar Daniel Kim terms ‘humanitarian Orientalism’: A wave of films that presented white Americans as benevolent saviors while reducing Koreans to infantile objects in need of rescue and moral guidance from the West.

One Minute to Zero (1952) channeled this notion through its central moral dilemma. Robert Mitchum’s Col. Janowski orders artillery strikes on refugee columns suspected of harboring North Korean infiltrators. While the scenes unfold with unflinching brutality, with set pieces intercut with real footage of fleeing civilians, the film’s ultimate drama rests squarely on Mitchum’s inner turmoil and his girlfriend’s gradual acceptance of the war’s harsh imperatives. As such, Korean civilian deaths are framed as unfortunate but justifiable collateral damage in the white protagonists’ deeply personal humanitarian quest.

Battle Hymn (1957) followed a similar formula. Here, Rock Hudson’s Col. Dean Hess takes in Korean orphans even as he carries out deadly bombing missions. The film blurs the line between humanitarian rescue and military strategy, portraying the act of saving orphans as a way to keep them away from communism. In so doing, it reveals the biopolitical logic of American intervention: Some Korean lives deserve protection, while others constitute acceptable losses.

Still, word about the war got out. In May 1951, the Women’s International Democratic Federation (WIDF), a private organization created during World War I, sent an international delegation of 21 women from 17 countries to North Korea to investigate atrocities committed by U.S. and South Korean troops during and after their occupation of the DPRK. MacArthur’s directive, they said in a report for the United Nations, “meant the revival of the fearful military tactic that had reduced considerable parts of civilian areas in Germany and Japan to ashes during World War II.”

The report, which was completely ignored by the American press, described in gruesome detail the impact of U.S. firepower. “The people of Korea,” it began, are subjected to “a merciless and methodical campaign of extermination which is in contradiction not only with the principles of humanity but also with the rules of warfare as laid down, for instance, in the Hague and Geneva conventions.”

The U.S. Air Force bombing, it said, was marked by “the systematic destruction of food, food-stores and food-factories” and “the systematic destruction of town after town, of village after village, many of which by no stretch of imagination could be considered to be military objectives.”

The Truman administration denounced the report and launched a vitriolic campaign of red-baiting to discredit the women, leading “to the labelling of the WIDF as a communist organization and its subsequent removal from the UN as a consultative organization,” wrote Suzy Kim, a professor of Korean studies at Rutgers University.

Yet despite the denunciations, some American generals involved in the bombing campaign were genuinely were shocked at what they had done, inadvertently confirming what was in the report. “I would say that the entire, almost the entire Korean Peninsula is a terrible mess,” Air Force four-star Gen. Emmett E. “Rosie” O’Donnell, Jr. a decorated World War II veteran, said afterwards. “Everything is destroyed. There is nothing left standing worthy of the name.”

Even MacArthur was shocked. “I shrink — I shrink with a horror that I cannot express in words — at this continuous slaughter of men in Korea,” he lamented during his famous Senate hearings in May 1951. “The war in Korea has almost destroyed that nation.” If the war continues, he warned, “you are perpetuating a slaughter such as I have never heard of in the history of mankind.”

Incredibly, nobody in Korea was spared the wrath of the American armada, so the damage was terrible in the South as well.

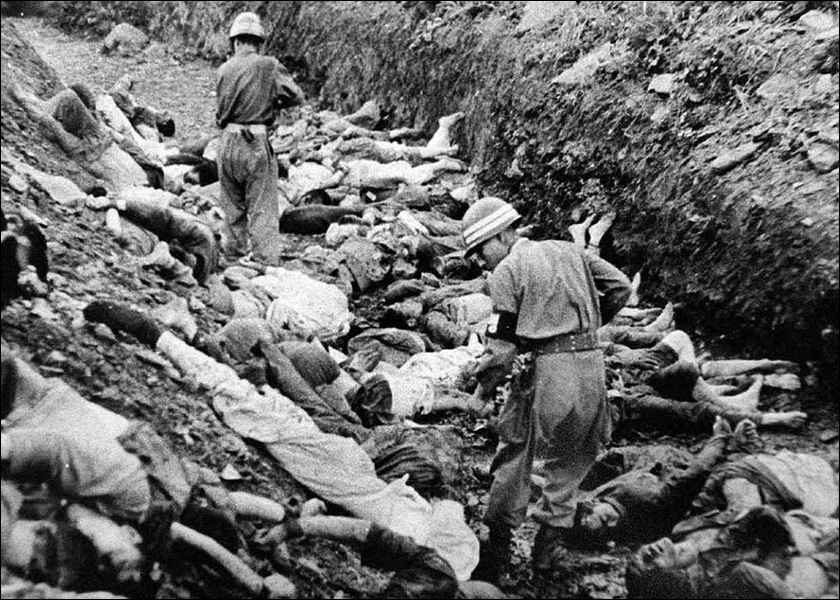

MacArthur’s forces began bombing runs south of the 38th parallel immediately after the North Korean invasion. In July 1950, a phalanx of B-29s attacked the Yongsan area of Seoul in a raid designed to kill North Korean forces billeted there; over 1,300 civilians died and were buried in mass graves. U.S. bombing and shelling elsewhere in the south killed many more.

“We even burned down Pusan,” LeMay boasted in an interview. “That was an accident, but we burned it down anyway.” Even MacArthur’s daring invasion at Inchon, considered to be one of the proudest moments in U.S. military history, was equally violent and preceded by a vicious attack that killed many Korean civilians. On September 10, 1950, according to a 2008 report by the South Korean government’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, U.S. Marine aircraft attacked the nearby island of Wolmi-do to “eliminate all possible threats” to the Inchon landing.

The result was an atrocity. The U.S. forces “saturated the populated east side of Wolmi-do with napalm bombing, rocketing and strafing of houses and inhabitants” and hit “children, women and the elderly,” the commission found. “There is a strong likelihood that U.S. forces were aware of the numerous civilians living in Wolmi-do, but there was no evidence” that they gave any prior warnings of their attack.

The South Korean commission (which did its work from 2004 to 2008 and was heavily criticized by the U.S. government) concluded that the devastation wrought by the Marines “cannot be justified under the principle of discrimination or the principle of proportionality.” At least 10 victims were verified killed, but casualties were likely much higher.

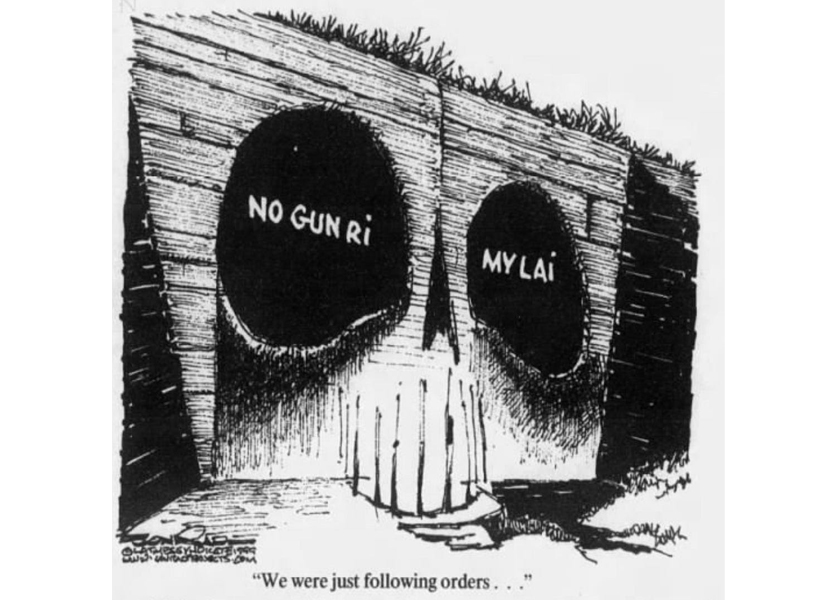

The commission also determined that U.S. forces were directly responsible for at least 300 dead at the infamous massacre at the No Gun Ri Bridge in the early days of the Korean War that was first uncovered by the Associated Press. The AP won a Pulitzer prize for its investigation (the U.S. expressed “regret” but never formally apologized).

In its final report, the Korean commission concluded that 86 percent of 14,373 executions in the south in 1950 were committed by security forces operating under U.S. control, Dong Choon Kim, a member of the commission, wrote that of the 1,222 incidents classified as massacres, “215 were found to have been committed by the United States military,” Kim added.

Sadly, the survivors of those massacres and the bereaved families had to hide their grief for decades because South Korea’s U.S.-backed authoritarian leaders, Syngman Rhee and Chung Hee Park, forbid any public acknowledgement of the deaths of anyone considered a communist or a subversive. It was only after South Korea established its democracy in 1987 that Koreans could learn their true history.

By supporting these authoritarian governments and denying its own role in the Korean War genocide, the U.S. participated in one of the largest cover-ups in history. The time is long due for a full reevaluation of the war and a national dialogue about its costs and consequences.