Pachinko TV series unpacks the history of Zainichi in Japan through one family’s perspective

(Directed by Kogonada and Justin Chon, from the novel by Min Jin Lee)

Review by Bo Brown (Summer 2023)

The first television series of Pachinko enjoyed rave reviews. Producers have now finished the second series which is due for release in early 2024 on AppleTV+. Based on a 2017 epic novel by Korean American novelist Min Jin Lee, Pachinko follows four generations of a Korean Japanese family. Series 1, consisting of eight episodes, covers roughly the first half of the novel.

As we wait for Series 2, it is a good time to consider what makes this production so special. The story is unique; it is a seldom-told tale of the Korean diaspora. The script is engaging, the acting is top notch, and the production values are excellent. The direction and editing are expert, and the music production is subtle and well thought out.

The bedrock of the production, of course, is its source material. Korean American journalist and author Min Jin Lee’s book of the same name has received numerous accolades for Pachinko. Lee’s first novel Free Food for Millionaires was a national bestseller. Pachinko quickly became a New York Times Bestseller and was a 2017 finalist for the National Book Award for fiction.

Lee embraces the voice of an omniscient narrator in this story, following all points of view instead of just one. This rather old-fashioned style of storytelling is not very popular these days, but the advantage is that the reader gains multiple perspectives on what is happening in the moment. The TV screenwriters have done a pretty good job of emulating that aesthetic without following it exactly.

The novel follows the history of the Korean diaspora to Japan. This group — which in Japanese is known as the Zainichi — is complicated indeed. Prior to World War II, when Korea was occupied by the Japanese, Koreans were encouraged to become Japanese citizens and to assimilate into that society. After the war, when Japanese rule was eradicated, Koreans’ rights in Japan were revoked. Even children of Japanese mothers and Korean fathers were rendered stateless, while children of Korean mothers and Japanese fathers retained their Japanese citizenship.

The term Zainichi in Japanese literally means “residing in Japan” and refers to all resident non-Japanese, not just Koreans. But the term has specifically been applied to Korean people whose forbears arrived long ago. In most societies, descendants from many generations ago would have a sense of themselves as being of the culture that they and their parents and grandparents called home.

However, in Japan, where Koreans were forced to serve the long-term occupiers of their nation and whose contributions to Japanese society were dismissed and even reviled, the term Zainichi might as well translate to “those people.” Korean Japanese have lived a contradictory, permanently-impermanent existence for all their years in Japan. The easing of anti-Korean policies after the 1950s and ‘60s has not completely repaired the damage to relations between Zainichi Koreans, North and South Koreans, and the Japanese. Even today, the Japanese feelings about Korean residents and Koreans’ feelings about the Japanese citizens can sometimes run high.

Lee, however, maintains a light, easy handle on her very serious subject matter. As she explores the story of this family, she describes their journey as just one example of the many stories of the Japanese Koreans. In an interview by the Shanghai Review of Books, Lee revealed she first tried to write about the Zainichi historical experience while in her 20s, but she was “writing from anger” and the novel did not develop well. She notes she didn’t have the perspective to fully understand the situation until she actually lived in Japan, and met and interacted with Korean Japanese people. She could not understand their lives until she understood them as individual people.

Pachinko is the name of a uniquely Japanese gambling game, and the connection of the Korean Japanese people with the game can only be understood in the context of history. However, approximately 80 percent of pachinko parlors in Japan are owned and run by ethnic Koreans. In the story, the character Sunja and her family runs such a business.

Although the game looks simple, everything connected with it — right down to how bets are paid out — is enormously complicated. It is an appropriate name for an epic story of a family that seems straightforward on the surface but has a lot of internal complications. Not to mention, the sheer joy of saying the word “pachinko” makes for a good title. It has a satisfying ring to it.

Pachinko is not a Korean television series. It is an original U.S. production by AppleTV+. The main production company, Media Res, is based in Chicago. The directors, showrunner, producers, and book author are all members of the 100-year-old Korean American diaspora. As an ethnic community, Koreans in America have been ignored in U.S. popular culture until the recent past.

The cast, crew, and locations in Pachinko are international. It was filmed in many Korean and Canadian locations, along with some scenes in New York City. Although the cast leans heavily on Korean nationals, Zainichi, Korean Americans, and other Americans, there are also some Japanese actors in the cast.

Three languages — Korean, English, and Japanese — are used throughout the series. The producers are careful not to deliver dialogue in heavily-accented English to try to indicate a character is speaking Japanese or Korean. Rather, the screenwriters scripted the language so that the characters behaved like the multi-lingual people they had to be in that era. For example, the Zainichi character Solomon moves easily from one language to another as the situation requires — speaking Korean to his family, English to his American coworkers, and Japanese to his Tokyo coworkers. Viewers see a color-coded subtitle translation to indicate which language is being spoken — yellow for Korean, blue for Japanese.

The language usage complicated the casting process. Aside from considerations of acting ability, actors had to already have good speaking skills in whatever languages they would be using. This worked to the production’s benefit. Commenting on this, showrunner Soo Hugh has noted that the most important people in the production were the translators, as everyone on set, cast or crew, at any one time might be a native speaker of one language or another. She felt working in this way helped bring the production together.

Central to the TV series is Korean actress Yuh-jung Youn. Virtually unknown in the U.S. before she starred in the U.S. movie Minari (2020), in which she portrayed a charmingly offbeat grandmother, Youn started her Korean TV career in 1967 and quickly became known as an up-and-coming talent in film and TV. She retired in the mid-1970s to follow her husband to the U.S., eventually divorcing and returning to Korea in the mid-‘80s. She started acting again as a way to support her two young sons. She overcame deep Korean prejudice against divorce, and gained the respect of audiences for her versatility and skill as a character actress. She took on a wide range of interesting roles. After her success in Minari, for which she won an Oscar and numerous other awards, she was already well known in the South Korean movie and television industries.

In Pachinko, Youn plays the oldest iteration of the main character, Sunja. She is not necessarily the cast member with the most screen time, but she undoubtedly sets the tone for the series. The narrative follows Sunja as played by three Korean actresses: As a child by Yu-na Jeon, as a young woman by Min-ha Kim, and as an old woman by Youn.

Although Youn portrays the elder Sunja with compelling dignity, and Jeon gives a lively performance as 11-year-old Sunja, it is really newcomer Kim who carries Series 1, playing Sunja as a teenager and young woman. Previously, Kim had had only about six relatively minor acting roles, but her ability is evident in Pachinko. She carries the role with innocence mixed with tough spirit and purpose. Although the two actresses bear a certain uncanny physical resemblance to one another, their ability to merge the two versions of Sunja shows their acting prowess. Their conforming of the younger and older Sunja into one character is a complete success.

The first episode begins in 1915 Busan, Korea, and describes events before and after Sunja’s birth. The action soon shifts abruptly to 1989 New York City, where Solomon Baek, a young American-educated, Zainichi man (soon revealed to be Sunja’s grandson), is a rising star at an investment bank.

The series continues to shift forward and backward in time, revealing the family’s history in large swaths, relating past to present. At first, this storytelling method can feel somewhat disorienting. But it soon settles into a rhythmic inevitability — one cannot imagine the story being told in any other manner.

Interestingly, in the source novel, the action unfolds in linear, past-to-present fashion. The world of the novel is astonishingly intimate. Even though outside forces shape the world it illuminates, and even though those forces are explored, they do not overwhelm the narrative. Each chapter feels like a private, extended family gathering where conversations about the family history take place in quiet corners. In the telling, the stories of relatives are revealed in all their limitations and glories.

But the TV series, a different animal, is necessarily bigger in scope. It is gorgeous, sweeping across landscapes and illuminating historical periods. One feels part of a thing outside everyday existence. As a whole, the series is a beautiful love letter to the old Korea and its people, Zainichi Koreans and others. It honors those who worked for freedom despite harrowing danger, as well as those who simply kept their heads down and took care of family and friends the best they could. The script pulls us in, inviting us to comprehend why they fought, ran away, or simply endured. More important, the storytellers clearly want us to feel what the people felt.

It is be impossible to mention all the fine acting work in Pachinko, the two male leads really stand out. Solomon is portrayed by Korean American indie actor Jin Ha, who tackled some challenging roles on television and also on Broadway, including the lead in M. Butterfly and Aaron Burr in the juggernaut Hamilton. Ha’s portrayal of Solomon is not immediately likeable, but he is somehow irresistible, a train wreck that we cannot look away from.

Born a Zainichi and educated in the U.S., Solomon switches between being an arrogant jerk and a vulnerable little boy. Ironically, although popular culture assures us that freedom from self-doubt will solve all internal issues, once Solomon allows himself to be free, it brings out his darkest impulses. Ha adroitly handles the character’s flips and turns.

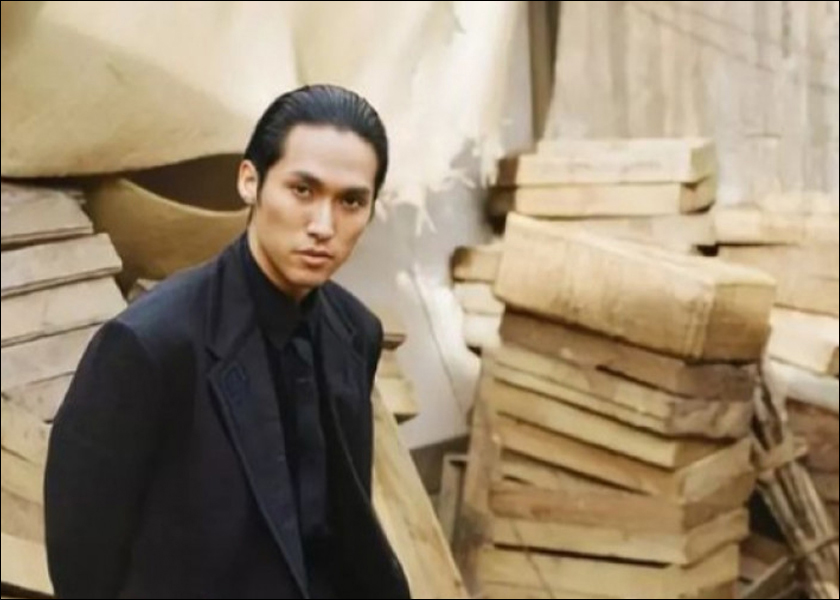

Like Solomon, the character Hansu (Sunja’s first love, played throughout by Korean heartthrob Min-ho Lee) is a complex fellow. His character is formed out of circumstances that are incomprehensible to more modern people, his behavior leans into nihilism and frightening practicality. In understanding the character, the story unravels important history that assists the viewer, but it is difficult to view him as anything but a charming monster. Lee rises to this complicated character’s role with no trouble at all.

The showrunner and developer, Soo Hugh, leaned into portraying multiple points of view by employing two indie Korean American directors, Justin Chon (born in Garden Grove, California) and Kogonada (born in Seoul). The two each directed four episodes in Series 1, bringing their own viewpoints to the storytelling. This seems to have been an excellent production decision.

Music is integral to the series, starting with a brilliant opening dance sequence featuring Let’s Live for Today by The Grass Roots. The last episode instead features pansori pop (traditional Korean folk song styles melded to modern rock) by the band Leenalchi singing its version of the same song.

In a nod to the time-traveling aesthetic, the opening sequence features cast members who don’t interact in the series (because they are from different timelines) performing a line dance together. It’s joyful, it’s fun, and it demonstrates what the viewer is about to witness: That while we all come from our own eras, we are all connected, although those connections may not be literal or obvious..

The novel Pachinko tells a story of many people, but it is the work of one person. A TV series is very different: It is, of necessity, the work of many, and it is strengthened by the cooperative work and diversity of all involved. Perhaps it succeeds because it emphasizes some universal themes, primarily, that finding a place to belong, striving and having hope for the future are necessary for us all.

Observing how the screenwriters respected these principles in the first series, we can trust the high bar set by Series 1 will follow through in the story of the second half of the novel in Series 2, which means, or fans of Korean popular culture and good television, that 2024 cannot come fast enough.

.