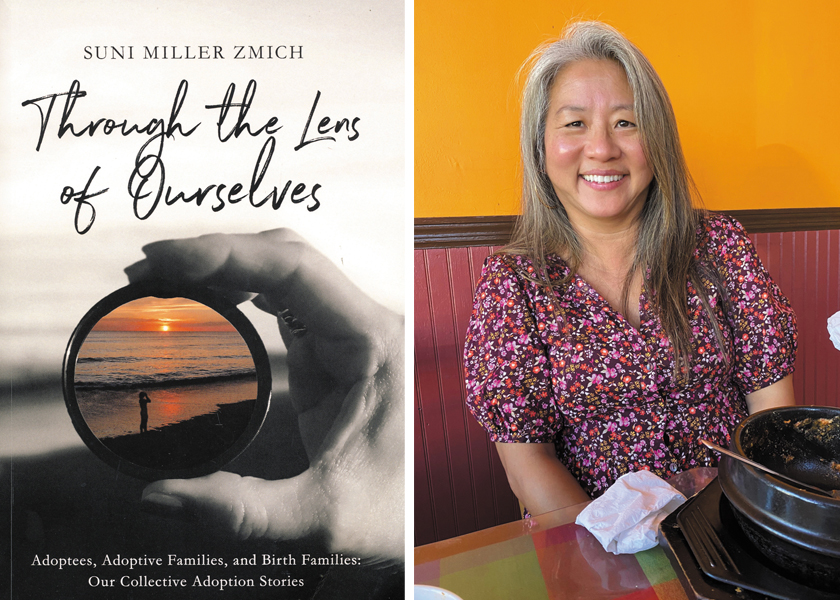

Author interview: Suni Miller Zmich captures perspectives from people connected with adoption in new oral history | By Martha Vickery (Fall 2021 issue)

Suni Miller Zmich has never published a book before, but she could feel a book brewing long before she quit her corporate accounting job in January 2020 to do research in the form of interviews of people who were directly connected to adoption – the adoptees, birth parents and adoptive parents.

She did the first interview in January 2021, and the project progressed quickly from there. She has since completed the editing with the help of two editors, and recently self-published it in e-book and printed form. It is a diverse collection of 34 stories: Seven from international adoptees; eight from domestic adoptees; 12 from adoptive families; and seven from birth families. The collection of oral histories are interwoven with a memoir about her own life journey as a Korean adoptee, and entitled Through the Lens of Ourselves.

Through the Lens is not only this Twin Cities author’s first book, it is her first writing project. It was a big career shift from working in corporate finance to being a researcher, writer and editor. A cascade of events pushed her to start the project.

Zmich, a Korean adoptee, said she was driven by a desire for a more meaningful pursuit. She had thought about talking to adoptees about their lives for a long time, and wanted to formalize it into a project. Initially, she said, “I felt relief I was doing something I could believe in, and that I could be my own boss.”

She liked certain things about her corporate job, such as the orderliness of accounting, she said. “I was contributing to bottom line, which is fine. I just didn’t want to spend the rest of my life doing that. I didn’t want to be on that hamster wheel. That continuous cycle of meeting deadlines, then closing the books. Then doing it again.”

Beyond that, and her curiosity about other adoptees and their families, she had no immediate thoughts about the book, other than to see where the project would take her. Her search for interviewees began with a Facebook post requesting help. Friends and family members responded, and they asked their friends and family members. Soon there were people she did not know contacting her and volunteering to be interviewed.

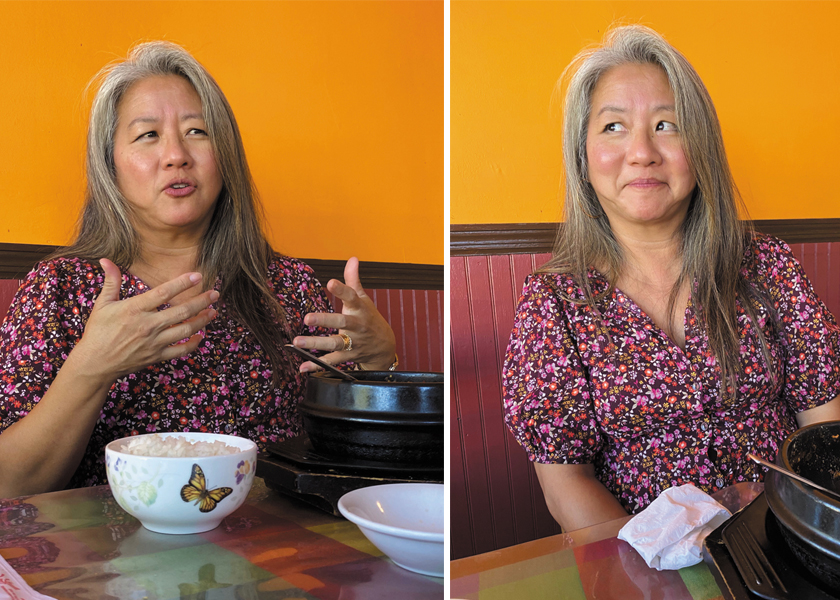

Zmich gives off a vibe of cheerful self-confidence. But she said she had many doubts while writing these oral histories. Each story took a lot of time, and some of the stories were hard to hear. As she got into some of the more tedious or emotionally taxing aspects of the project, she had moments where she thought “’What the heck am I doing and why am I doing this?’” Zmich said. However, she said, there were some encouraging “nudges” along the way, enough to persuade her that every story was being told to her for a reason.

She had no notion, while in the process of research and interviewing, about the project changing her life, but it did. She said she just tried to be open to whatever story she heard. She feels “more evolved and more settled now” she said, and she thinks the feeling came from talking to so many birth mothers who placed their children for adoption. “I was always angry about my adoption, and walking through each story, hearing and feeling what these birthparents felt, completely just transformed me.”

These days, Zmich lives and breathes adoption stories, and talks to people about them often. However, not so long ago, she did not talk about adoption at all. Part of the change in her own thinking was about the people she talked to, and how their perspectives changed her.

Zmich refers to herself as “an Army brat.” She was adopted from Korea while her father was stationed in Korea, and lived in many places; 34 moves from birth to the present, she wrote. Travelling and always going to new schools, she had little sense of home or stability as a kid; she confronted racism at school and elsewhere. Doing the interviews and engaging in so many conversations with people involved in adoption was the first time she reviewed her own past, and the emotional fallout of her upbringing as an adoptee, she said.

Zmich and her husband moved with their two daughters to the Twin Cities area in 2002 due to her husband’s job change. She had not been involved any the local Korean adoptee community organizations until recently. After reaching out because of the interviewing, and more recently in promoting the book, that changed too.

The interviews also showed her that she was not alone in having unresolved emotional trauma. Fellow adoptees, she said, all deal with the trauma differently. “Some get depressed, some become workaholics. Some, like me, just stay angry.” Her anger was “a tool,” she said. “It kept me from drowning in depression. But it also kept me from being free. If you are mad about something, you have control. You can push it to the side, so you can function.”

Staying in that state, however, is exhausting, she said. Her recent sense of freedom has come from being able to finally leave the anger behind, and move on to other steps in her emotional life, toward a sense of compassion for everyone involved in adoption.

The author said she did not pick and choose what stories would make it into the book. Instead, she felt responsible to every person who told their story and decided to include all of them. She treated the people who came to her carefully, worried that they would be nervous. She did much of the interviewing on Zoom during the pandemic lockdown, typing furiously while the person told their story. She sent the interviewee a draft to review before it was final. On the advice of her lawyer, she used pseudonyms names for everyone, to protect them and any family member who might read the stories, as well as herself.

Because of how she found the interviewees, all of the adoptive parents and all of the birth parents who were interviewed are Americans. There is, however, a good representation of inter-country adoptees who grew up in the U.S., in addition to domestic adoptees.

There was a spectrum among interviewees in their readiness to tell their story and degree of openness they were willing to have about it. “Some had told the story before, and some had not,” she said. “There were a few moments when people would say ‘oh, I never said that before to anybody or really thought about it from that angle.’ Some people are very in tune with their emotions,” while others are shut down and cannot articulate how they were feeling at a particular moment, she said.

The author discovered that “some people are very fearful of their stories,” she said. “One story in the book is very short, but that’s because it was cut. When the person read her [final] draft …she couldn’t agree to it, it was too painful and too much for her. I had to take most of the story out.”

Other interviewees were very proud of their story. “They would put it on Facebook and say it was them.”

Some interviews reveal that when birthparents seek out their birth child, an emotionally-harmful situation can result; others describe reunions with birth families that are a benefit to the adoptee and the adoptive family.

One story, from the perspective of adoptive parents Emma and Art, reveals how an adoptive family promises to have an open relationship with a domestic birth family, only to regret it when finding out how dysfunctional the birth family is, and how harmful the relationship is to their children.

Similarly, the narratives describe adoptees who reach out to birth family only to be rejected, while others do the same and are welcomed. The story of Nicholas L. is one such story with a joyful ending. Born in Greece in 1954, Nicholas was adopted as a toddler. In 2008, at age 54, he is contacted by the adoption service and told birth family is looking for him. After receiving a big package of translated letters and photos of his Greek family, Nicholas returned with his wife to Greece later in 2008 to meet his birthmother and a very large family, and a warm and wonderful relationship was the result.

In addition to their story, each interviewee got a chance to give some observations or advice they have gleaned from their own lives, targeted to others who are involved with adoption. There is a wide range of experience represented in the collection. Some of the advice is contradictory.

Zmich said the advice offerings at the end of each narrative were not meant to be anything but a chance for an interviewee to reflect. Whether it is good advice or not is up to the reader. In any topic involving adoption, she said. “You’re not going to find a roadmap. If only there was one!” Growing up adopted or parenting an adoptee is as individualistic as the people themselves, she reflected. “I just wanted to give a sampling, to perhaps give prospective adoptive parents an idea of what could happen.”

She also thought it was a useful exercise for the interviewees to do, and for the reader to have as part of the narrative. “Everybody has an opinion of how things should be done. Everyone has regrets of things they believe they could have done better,” she remarked. “And regrets are very useful – you can try to help somebody else. The whole cliché of don’t reinvent the wheel? I think that’s what I wanted to do with that part.”

Although the author is involved in the publicity-generating phase of book publication right now, what she really wants to do is write, and she has a new book idea percolating. “In the next book, I want to go even deeper, and really explore motivations and reasons behind why people want to look for their birth parents, or why birthparents want to look for their offspring, or how adoptive parents feel,” she said.

Her next book topic, Zmich said, will focus on the search for birth family. She wants to capture interviewees accounts of their searches while they are in the process of doing it. Parallel to that, Zmich said she will be renewing her own search for birth family, which she began but then suspended, in the early 2000s.

Her international adoption was not typical, she said, because her father was stationed there and he dealt directly with the Korean agency. She was told that her documentation had been lost, she said, “but I am not sure if I quite believe that. I think I am going to dig into that.”

Zmich’s website has a call for participants, stating “I am specifically looking for adult adoptees and birth parents who have not previously searched for their biological families or offspring, but are ready to begin the process. My hope is that we can work throughout your journey together, as an adoptee, I am also ready to embark on that intimidating personal quest.”

The author’s website, with a blog, quotations from the book, and information on how to connect is at: sunimillerzmich.com