How a peace treaty would change the focus to reducing climate risks on the peninsula | By John Eperjesi (Fall 2025)

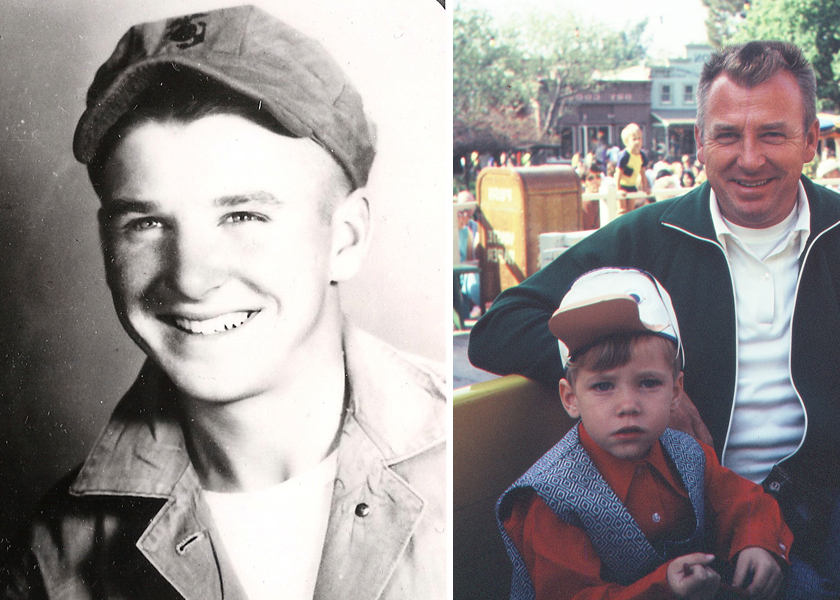

In the summer of 1952, my 18-year-old father entered the Korean War. After reading the Second Battalion, First Marines Command Diary and histories of the Marines in western Korea at the time, I think he was probably involved in one of the many battles over Bunker Hill (Hill 122). When I saw Jang Hoon’s amazing film The Front Line (2011), I got a rough sense of what my father experienced during the war, and why, according to my mother, he never talked about it.

Shortly after arriving in South Korea for his tour of duty on September 5, 1952, my father was hit by missile fragments and received wounds to his thigh, buttocks, Achilles tendon, scalp, and face. He lost one of his testicles but gained a Purple Heart.

Because of his wounds, my father could not have children the old-fashioned way, so I was adopted, which means my destiny began to take shape the moment he was wounded in the Korean mountains.

My father died of a heart attack when I was eight, so I never got to ask him about the war, but I often think his spirit guided me here to South Korea 18 years ago to learn more about Korea and the Korean War. He helped me find a wonderful home, both in Seoul and in the mountains.

President Jae Myung Lee recently emphasized in his Liberation Day address the importance of dialogue with North Korea to reduce military tensions in the hope that peace-building can lead to eventual reunification. We need to end the Korean War and stop the New Cold War. This region doesn’t need any more wars, cold or hot. As Lee said, “We need to move beyond Cold War mentalities.”

In addition to urgent humanitarian reasons for replacing the Armistice Agreement with a peace treaty, such as the reunification of millions of divided families who want to embrace each other before they die, a formal end to the Korean War would be an opportunity to move away from the carbon-burning militarization of the peninsula, and toward combating the most urgent threat to life in Korea and on this planet: Climate breakdown.

This is a critical moment in the history of the climate crisis. The extreme weather events we are experiencing now in South Korea — wildfires, flooding, heat waves, drought — are going to get worse in the coming years, and it is going to be expensive. Reducing military tensions means more resources can be directed toward protecting vulnerable communities during heat waves, such as the elderly, around 40 percent of whom live in poverty.

Reducing military tensions means more funding for a just energy transition that supports the dignity of workers and the health of working-class communities. During the transition process, people living in coal mining towns like Dogye in Samcheok cannot simply be abandoned but need to be included as the country tries to meet climate goals, in the form of job training and free education. They need to know that their lives, experiences and struggles matter.

Reducing military expenditures means more funding for weapons to fight the “heat island effect,” such as “cool pavement,” which involves painting streets white to reflect the sun’s heat, and for the planting of and caring for millions of trees, the best weapon to counter mass carbon destruction and promote urban cooling.

Instead of preparing for combat with North Korea, we should wage an all-out war on drought by building the groundwater reservoir dams which were proposed by the Ministry of Environment to provide “water insurance” for places like Gangneung. Local governments, particularly those in rural areas, have tight budgets and aging populations, and desperately need financial and planning assistance to deal with climate disasters.

“Ending war and genocide” was one of the six fundamental demands of the 927 Climate Justice March which took place on Saturday, September 27 in Seoul. The other five demands include: Climate justice-based goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and conversion; a just energy transition; a stop to one-sided growth policies and harmful development projects; strong public services for safe and dignified lives; and farmers’ rights and the right to healthy food.

The climate justice marches in Seoul began in 2019 and were inspired by Fridays for Future and global climate strikes. Every September, the demonstrations for the planet and against climate breakdown get bigger and louder and angrier. But they are also celebrations of all life on this planet, of multispecies entanglements amidst biological annihilation and mass extinction.

In Korea, reducing military tensions as a step toward ending the unending Korean War will provide some of the resources needed to meet the demands of the climate justice movement in South Korea. Decarbonization and demilitarization need to go hand in hand as the country works to mitigate and adapt to the climate crisis.

As the crisis intensifies, everyone on the Korean peninsula needs to fight climate breakdown together. The climate crisis is a portal, an opportunity to break with Cold War mentalities and imagine new ways of living and flourishing together on a damaged planet.

I often imagine attending a ceremony to celebrate the official end of the Korean War. Veterans and their families probably experience a spectrum of conflicted emotions about the war and the prospect of a peace treaty. Even though I’ve been very critical of the U.S. involvement in the war in my academic work, I would proudly display my father’s Purple Heart at a peace treaty ceremony, which would give all of us a moment to express how we feel, both about the past and the future.

I look forward to the day when I can shake the hand of North Korean and Chinese veterans of the war, show them my father’s medals, and throw back a shot of soju with them.