Author Interview: Grace M. Cho honors the Korean diaspora, and her mother’s life, in Tastes Like War | By Martha Vickery (Winter 2023)

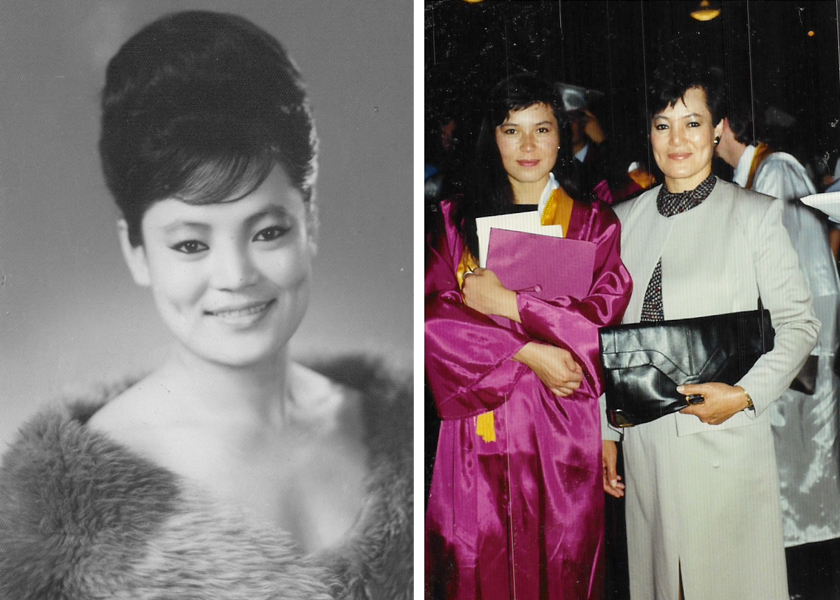

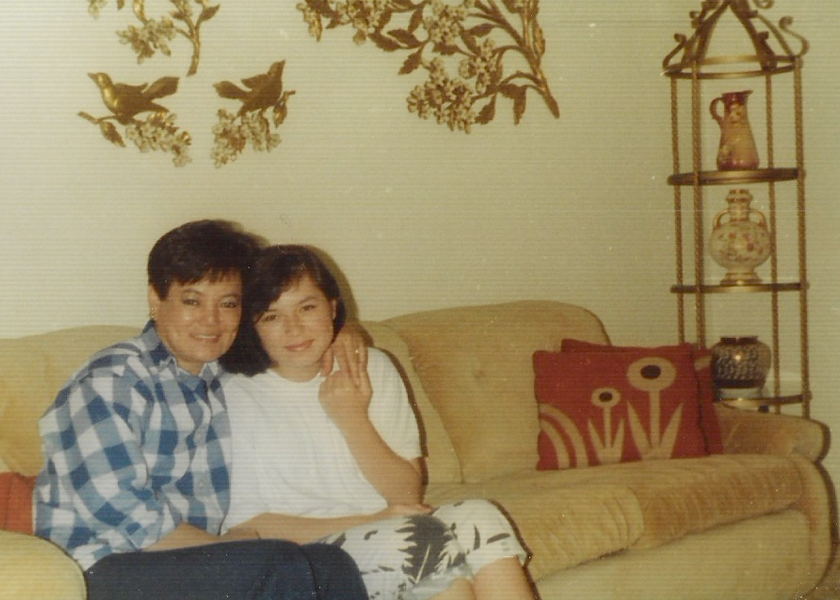

Author Grace M. Cho, like many who lose a family member after a long illness, had a period of grieving where she could remember only the sick and helpless mother she had been trying to help in the years leading up to her death. But this period was followed by a healing time during which she began to remember the healthy, gifted, energetic mother she knew through her childhood and teen years.

Writing down her memories was the beginning of a complex memoir, Tastes Like War, about her mother’s life, and her own life as her mother’s daughter. Intertwined in the stories and emotions of the memoir is the harsh backdrop of post-war Korea that her mother survived, the oppression of the U.S. forces in South Korea, the shock of immigration and the constant stress of surviving in a rural white society. She also links her mother’s early and continuous trauma, including being cut off from Korea, to her descent into schizophrenia, and her eventual death from that disease.

She also writes of her mother’s creativity, especially when it came to food, and how preparing and eating Korean food together was a healing force in their relationship.

Tastes Like War was the winner of the 2022 Asian Pacific American Literature Award for Adult Nonfiction. It was also a finalist for the 2021 National Book Award for Nonfiction. Beyond those honors, Cho has toured widely to discuss her memoir and her research into immigration and war trauma, and its effects on survivors’ long-term mental health. She has heard many stories from readers whose experiences were similar to her mother’s; connecting with others’ stories has been validating.

Cho is a professor of sociology and anthropology at City University of New York (CUNY) at Staten Island. Her writing style is engaging in that she writes about psychological/sociological principles at a micro-level, through people’s lives; as well at a macro-level, in analyzing the effects of the U.S. military presence on the Korean people during and after the Korean War.

Understanding the Korean War through survivors’ stories was also written into her breakthrough study, entitled Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War (2008), for which Cho received an American Sociological Society book award in 2010. At CUNY, Cho teaches on topics having to do with war survival, immigration and trauma.

Although it is a memoir, and more personal than her previous works, Tastes Like War continues the same strategy as her first book, Cho said. She explained that she tries to find “creative methodologies for exploring social issues; prior to publishing my first book, I even did some performance artwork related to the themes I was exploring academically.”

In graduate school, she recalled, one of her advisors, a proponent of experimental writing as it relates to trauma, got her thinking on how to better communicate the effects of trauma. How past life experiences reverberate into the present and future was apparent to her – how to talk and write effectively about the topic became her cipher to crack. The puzzle, she said, was “how to communicate something that is more on the level of the affective, or more on the level of the unconscious.”

One of the author’s first experiments on alternative ways to teach about war trauma was as a performance artist in the touring art/video/audio exhibit Still Present Pasts: Korean Americans and the “Forgotten War,” The exhibit was once co-sponsored by University of Minnesota Institute for Advanced Study and several Twin Cities Korean American organizations in 2007. Cho and co-collaborators Hosu Kim and Hyun Lee did a performance piece for that exhibit.

That the exhibit was built around not only survivor experiences but also the memories of children of survivors resonated with her, she said. She remembers that she “really related to what some of the second-generation children said about feeling haunted by what their parents didn’t talk about, so that’s sort of how I started doing more creative work on this within academia.”

Cho writes in Tastes Like War how she received news of her mother’s death just before publication of her first book, Haunting the Korean Diaspora. In that study, Cho describes the dominating presence of U.S. military in South Korea, and its effect on the impoverished and powerless Korean people during the post-war years.

Exploring this cultural and sociological milieu became her way to understand her mother’s life, her illness, and her sudden death. “I imagined her in every scenario I wrote about,” Cho relates in Tastes Like War. “My mother was the figurative ghost of my book, and she began haunting me in a new way once she was actually dead.”

What sparked Tastes Like War was writing “just as a way of remembering all the little things about my childhood that were coming back to me,” Cho said. During her young adulthood, she said, “my mind was consumed by dealing with the trauma of my mother’s mental illness and trying to understand her past in Korea, and of uncovering a history that was just really heavy.”

Remembering her mother’s life was “joyful,” she said. From the perspective of her childhood, her mother was bright, energetic, capable and creative. Despite the weight of grief “I was able to recover those memories, and I realized I had forgotten so much about her because of the heaviness of her schizophrenia.”

She writes of her mother as a clever forager, who was able to find the best places to pick fiddlehead ferns (gosari), burdock and seaweed – all common wild greens for Korean tables. Later, she discovered she could make good money foraging for wild produce that was in greater demand – mainly mushrooms and wild blackberries. She also made and sold blackberry pies and jam. During the height of foraging seasons, she seemed driven – walking the woods by day, and working at a part-time job by night. Her father, who had been a merchant marine, was older than her mother, and had several heart attacks during her teen years. As he slowed down, her mother sped up, and provided income and other support for the family.

Although her mother was known and liked in the community through her foraging business, her skillful cooking, and other work, she was not truly accepted, the author writes. The cultural divide was wide and the systemic racism deep in rural Washington state. It affected Cho and her brother as well.

Cho described herself writing in a state fueled by grief. She penned bits and pieces of memory. A common interest in Korean food bound their mother-daughter relationship. Her mother’s energy for cooking and feeding people was always extravagant. Cho relates craving her mother’s flavorful food after her death. Food was part of the grief, but also part of the solace and healing.

Cho relates that she was also hungry for her mother’s stories of home, which her mother parceled out sparingly. Sometimes she revealed shocking facts, for example, when her mother talked about her sister – an aunt who Cho had never heard of. Cho writes that her mother told her about her one day, that she had suddenly disappeared during post-war confusion, and she never found out what happened. Cho knew that there was many more stories her mother left untold. She pieced fragments together as well as she could over the years.

“Originally, when I started developing those memories into memoir pieces, I wasn’t thinking I was going to write a memoir,” the author reflected. She thought she might “develop it into something.” Feeling unfamiliar with the genre of memoir, she signed up for workshops with other writers who were doing memoirs.

The workshops were encouraging, as the writers’ cohort swapped stories and shared their challenges. “I kept getting this feedback that it seemed like I was holding back on something, and that there was a bigger story,” she said. “I was sort of reluctant to put that in, because I had already written a book [Haunting the Korean Diaspora] about the back story.” But because her group told her the back story needed telling, she incorporated some of the research described in her first book. “Once I made the decision to make this another hybrid text mixing research and memoir, then I started to research other areas as well, and more specifically, around schizophrenia.”

Cho’s instincts always told her that her mother’s schizophrenia was, in part, caused by her traumatic past. A war survivor, Cho’s parents met when her father was a merchant marine and was visiting Korea. After they married, Cho’s mother and father along with her older brother settled in his hometown in rural Washington in the late ‘60s. After that, Cho’s mother was isolated from anyone who could relate to her experiences.

In her research, Cho theorizes that the mental health issues of many immigrants are linked to their past, particularly those who fled their home countries due to traumatic events like war, and landed in a vastly different culture, where their experiences were not recognized or validated. These characteristics, called social risk factors by the psychology community, are increasingly recognized as contributors to schizophrenia. But when Cho’s mother was first suffering, social circumstances were not seen as risks.

Her mother’s behavior began to change when Cho was a young teenager and got progressively worse. As a child, she recalled “it did not sink in for me that it was a real struggle for her to make it in that community.” As a teenager, Cho tried in vain to understand her mother’s behavior but was often terrified, mystified or embarrassed by it.

As she got older, her need to understand only deepened. “My mother was a mystery I was trying to solve, and it was what drove me for much of my adult life, because of my own traumas of witnessing her mental health unravel when I was a teenager and being so helpless, and not finding any sort of support for her.”

As a researcher, Cho explained, her curiosity also sent her to the scholarship around her mother’s illness. She started reading the work of experts who theorized that schizophrenia is not an isolated pathology, but is wholistically related to one’s past, particularly to past unaddressed trauma. She concentrated on “the social risk factors for schizophrenia that were linked to immigration and to being a person of color in a white neighborhood.”

Cho said she also found that in other cultures, schizophrenia is not thought to be an irreversible condition; other cultures view it as a condition that sufferers can recover from. That Western experts today still treat it as chronic could be one of the factors that makes it worse for patients in the mainstream U.S. health system, Cho said. It is also the most stigmatized mental illness, she added, “which does not bode well for recovery and also changes the dynamic of the family.”

In cultures where schizophrenic patients are expected to recover, Cho said, “families and communities do a much better job of integrating their person and keeping them connected to day-to-day activities, whereas in the U.S., we tend to ostracize and separate those patients.”

Hearing voices is a symptom of schizophrenia; Cho’s mother also heard voices. The traditional Western medical model is to think of this symptom as “purely biological,” Cho said. Therefore the patient gets medicated until the voices go away. This requires some powerful drugs that are unsafe in many ways.

Western psychiatry is only lately beginning to look at factors such as the patient’s social context and life history, the author explained. “Hearing a voice was automatically grounds for diagnosing someone with a serious mental illness, whereas in some other contexts hearing a voice could have a different meaning.”

When Cho was 23, just starting her Ph.D. program, her mother separated from her father and moved to New Jersey, near Cho’s older brother’s home. Cho’s sister-in-law told her, while Cho was visiting at her mother’s new home, that her mother was getting worse. She also eventually told her the part of her mother’s past she did not know, that her own brother remembered but never told her. “Grace, your mother used to be a prostitute.”

In time, her brother and father both confirmed it to be true. She experienced the shock of finally knowing the family secret, followed by sadness and shame. In dealing with it, she writes that the shame was something “that I would later come to interrogate and beat into submission through my research.”

After learning that her mother had a past as a sex worker, and in watching her mental health decline further, Cho said, “it sort of became a life mission for me to want to understand her in a deeper way and through a lens of compassion because I started to realize how stigmatized she was because of her association both with the U.S. military bases in Korea and because of the label of being schizophrenic.”

Cho’s mother never told her directly that her past included sex work – and Cho never directly asked. She learned in her research about the era, that in Korea, “from the time the U.S. troops arrived until pretty much until the present day, there has been sort of a stigma attached to women who fraternize with American soldiers …a woman could be a bar hostess, or a cocktail waitress, or a singer in one of these establishments, and even if she is not explicitly a sex worker the assumption is always there.” The way the stereotype affected the women psychologically at that time, and during their lives, is much the same, she said.

Cho said she wanted to honor her mother’s truth in living bravely and authentically despite the constant stressors her mother experienced as an immigrant of color, and despite the crushing weight of her past trauma. She also wants to honor the women of her mother’s era, whose hidden labor in the camptown neighborhoods near U.S. military bases lifted up South Korea’s economy from very dark times.

Cho said she also wants to honor her with the witness of her own memories of her mother’s life “as this person who was, in a way, so powerful in the community even though she wasn’t respected by that many people …that she was somebody who fed and nurtured people even if they didn’t see her as an equal citizen.”

The author sees her mother as typifying so many immigrant women in the U.S. “They have to work all of these really difficult jobs that no one else wants, and sort of bear the brunt of misplaced anger and racism.”

Cho knows her mother’s life goal was to be an educated person. “That was denied her, but the second-best thing would be for her children to become educated.” There is a through-line in the story, Cho said, “about how much she emphasized education being really important for me, and that it would somehow redeem her and it would allow her to sort of let go of some of the traumas from her past that made her feel ashamed.”

It is a Korean ethos, that if a child grows up to be successful, that the parent can feel that they did something right. “She pushed me to get my Ph.D.,” she said. The energy Cho needed to get through a Ph.D. program was a combination of “her making it so apparent that she wanted me to do it, and also my desire to give her something to look forward to during her darkest moments.”

Her mother died many years before the author thought of writing a memoir, but Cho reflected, “I imagine my mom seeing the success of my memoir as her success.”

In contrast, she added, her family members, particularly her brother and his wife, made it clear they did not want her publishing anything related to their family’s history, and were opposed to her writing her first book. She did not let their feelings deter her. “My mom actually was supportive of my first book, and she was the only person whose opinion really mattered to me.”

Cho said in a more recent interview that she has continued to be asked to speak about her research and her memoir during 2022, and it looks like 2023 will include many appearances on college and university campuses. “My head is still very much in Tastes Like War. I haven’t really been able to move on to anything new since then, which is fine, and I’m happy to do that.”

The book is in the process of being translated into Korean, and her next small project is to write a preface to the Korean translation for a Korean audience. “It is something that will be very emotional to me, because I will be speaking to the society I felt my family was exiled from. I will frame it around questions of exile, and homecoming,” she said. She will also visit Korea next year with her nine-year-old son, a trip that was postponed due to the pandemic. She expects to do one book launch event there.

Cho said she is also working on a children’s book of a story of a little girl and her mother. The mother hears voices, and the child tries to understand how her mother hears things she cannot hear.

During this academic year, she has been teaching a course on the sociology of mental illness, and some of the ideas concerning possible links between socio-cultural conditions and risks of mental illness (explained in a book she quotes in Tastes Like War entitled Our Most Troubling Madness by T.M. Luhrmann and Jocelyn Marrow).

Now, more than a year after publication of Tastes Like War, Cho has benefited from the supportive comments from a wide and diverse readership. Many are readers who “have had someone in their family who has been diagnosed with a mental illness, or who themselves have been diagnosed with one.”

Another group of supporters, surprisingly, have been from her hometown of Chehalis, Washington. “I don’t hold back at all in my critique of that town, yet I’ve had a lot of people from the town either reach out to me to say they also experienced it the way that I did, or maybe they didn’t experience it that way, and they are sorry and apologized for being complicit with a lot of the things that I described in the book.”

More broadly, Cho said, “what I hope it can do is to give more people the courage to speak about things that were told we’re not supposed to speak about, and I think, particularly around those experiences that we call mental illness, or around [experiences] like sex work or war trauma that are supposed to be so shameful, that we should never talk about them again.”

Delving into the research for the original thesis that became Haunting the Diaspora, which was then incorporated into Tastes Like War, was also something she personally needed, Cho said, “for my own sanity and to understand my family history.” In psychoanalytic language, Cho said, bringing up a topic that has been shrouded in silence is like “releasing the ghost in a public arena” she said, “so that’s exactly how I have thought about my writing, as carrying the legacy of the trauma and wanting to, I guess, escape the grip of the ghost so that it’s not so powerful, by making it public.”