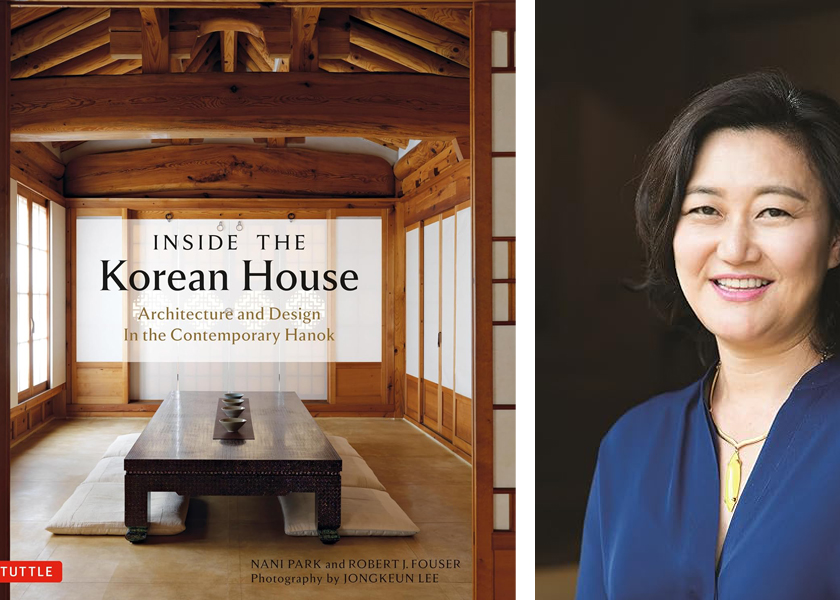

Inside the Korean House: Architecture and Design in the Contemporary Hanok ~ By Nani Park and Robert J. Fouser

(Tuttle Press, North Clarendon (VT), 2023, ISBN #978-0804-85046-9)

Review by Bill Drucker (Fall 2024)

Although Korea’s urban landscape is constantly changing, traditional architecture persists among the tall glass-and-steel structures. The aesthetics of harmony between man and nature still thrive. The best examples of simplicity, functionality and beauty by design are reflected in the Korean hanoks,or traditional homes.

This architectural study examines the hanok’s uniquely Korean history, design, and structure. The first hanok or chosonjip (both literally mean “Korean house”) were built in 14th century Korea and Manchuria.

Hanok designers apply the principles of fengshui (in Chinese) or pungsu (in Korean) in the design of each house and its location to ensure it is aligned with nature and the earth’s energy. The right location is scouted using geomancy; ideally, mountains are at the rear of the home, and a river or stream is to the front. Hanoks are usually made from local natural materials such as wood and stone.

The designs of these houses vary, but there are many common elements. In the colder northern regions, the hanok is a created in a square design with a center courtyard to retain heat better in the winter. In the southern regions, the hanok is generally made in an L-shaped design to be more open for optimum airflow and light.

The authors have made liberal use of interesting photos and a large format to allow the houses to speak for themselves. The reader/viewer is able to see how modern designers have kept the design principles and spirit of the Korean house, while adapting the design to modern living.

Because of the colonial Japanese occupation (1910-1945), Korean War (1951-1953), and the era of post-war poverty, the construction of hanoks stopped for a long period of time. Many of the remaining homes fell to ruin. After the nation began to recover economically, there was a trend to preserve traditional Korean arts, including performing arts, visual arts, design, and even traditional agricultural products and cooking. In the obsession to its national identity, hanoks were also revived and renovated, and new hanoks were built.

These hanoks, most of which were new or newly-renovated in the post-war era, are frequently studied by scholars and historians. The structures have been renovated and maintained by designers and architects. Today, it is rare for new hanoks to be built, due to the high cost of and urban real estate and custom building. There is also the matter of practicality of hanoks compared with more cost-effective and efficient modern home designs.

As with the Buddhist temples, hanoks possess a spiritual quality. They invite, they welcome, they offer the very best of shelter for the mind, body and soul. This book offers a tour of 12 of the best Seoul hanoks.

There are several grander hanoks in Seoul, and many more that are more humble. One fancier Seoul-area hanok, Oidong Pyulchang, was due to be destroyed in the 1950s during a movement to tear down big estates in order to replace them with smaller and more-efficient housing. The house was saved by moving it to a remote site outside the city. This hanok reflects the grandeur of pre-war upper-class estates. The current owner is a Swedish woman, whose family has lived there since the 1960s. There are European accoutrements, however, this hanok has retained many harmonious Korean design elements.

Another Seoul residence with a grander history is in the Anguk Dong neighborhood. The Yun Posun Residence was the home of South Korea’s second president, and was later occupied by his son. Its common rooms, used to entertain important guests, reflect an upper-class opulence. Other rooms reflect a more traditional simplicity and its outside gardens encourage rest and quietude.

Several hanoks are known for their thematic designs. Known as “the house of emptiness,” the hanok known as Mumuheon is designed to reflect the austerity of the Zen Buddhist tradition. The principle of mu/wu or emptiness is everywhere, yet the design is also pleasing and inviting. The house has no chairs or beds. Instead, there are wood floors with cushions. The floors are heated using the traditional ondol method, with pipes running under the floor. In tradition, the smoke from a fire on one side of the house would be routed underneath the floor. This house is now heated by hot water running in the ondol piping system.

Another unusual hanok is Bansongjae, which has a living pine tree incorporated into its structure. Situated on a hill in Samcheong-dong, the home has an upper and lower level. Because of its elevation, this hanok has splendid views of the city and Inwangsan (Inwang Mountain).

There are several houses described that are a combination of traditional ideas and modern design elements. A hanok in the Gahoe-dong area, Janyeongseosil, is known for its wooden lattice work that captures the lights of the city at night and the sun’s warmth during the day. The house is designed with a southern exposure intended to be cool in the summer and warm in the winter. A long, open terrace of wood connects the house to the courtyard.

A more modern hanok, called Moto Hanok, is also located in Samcheong-dong. Modest and small, it is designed to be modern and comfortable for a family. Most rooms have views of Inwangsan and the city. The design exploits every space for an innovative feel. Bicycles hang from the wooden beams. Ceiling windows allow natural light to flow into the rooms.

Hwadongjae or the “house of becoming one with others” is in the village of Joanni, and the only hanok in a rural setting. The hanok is notable for exercising contrasts; traditional versus modern, formal versus casual, and urban versus rustic. Its design is minimalistic, with functional living space incorporated harmoniously with outdoor space.

This is a beautifully-produced coffee table-style book. The large format allows for some inspiring and detailed images that reflect the Korean ideals of harmony, tranquility, and resilience. The authors follow the rules of hanok style by design by letting the houses speak for themselves. Just a one-page description of each hanok is all that is required for the reader to learn about and appreciate the unique Korean structures that stand up to, and may possibly outlast, Seoul’s many cold, concrete towers.