Adoptees for Justice calls on supporters in key states, more constituent support | by Martha Vickery (Fall 2022)

In the waning months of 2022, at the end of a long year of lobbying and visiting constituents, supporters of the Adoptee Citizenship Act (ACA) are hoping their bill will finally get over the finish line in the Senate, during the session that continued as of September 6, after a summer break. (See KQ last update on the ACA that ran in the Fall 2020 edition)

The ACA, a proposed law which would confer automatic citizenship to all international adoptees, was passed in the House of Representatives in February as part of a large trade-centered bill, the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act (nicknamed “the Competes Act”), which is designed to increase U.S. semi-conductor manufacturing, and deal with supply chain issues of manufacturers in Asia.

All bills must be passed by both houses of Congress, so after that passage, the bill went to a conference committee before being sent to the Senate. After going through the conference committee process, ideally when two versions of the bill are reconciled, a version of it was passed in the Senate, and eventually made law in late July, as the so-called CHIPS-Plus Act (the long form of the CHIPS-Plus Act is the “Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semi-conductors for America” Act).

However, in the process of the compromise, the ACA was stripped from the bill, along with other added provisions. Since July, the strategy has changed, but the fight is still on to ensure citizenship for all adoptees, with help from Asian American organizations and Korean adoptee groups in several key states.

Adoptees for Justice (A4J), the national education and lobbying organization sponsored by the National Korean American Service and Education Consortium (NAKASEC), has used the last few months to re-boot, and lobby for the ACA to be passed in another form, either as a stand-alone bill, or as part of another bill.

If passed, the law would cover all international adoptees. It would confer citizenship on all children who will be adopted internationally in the future; it would also confer citizenship on any international adoptees who currently do not have U.S. citizenship.

Taneka Jennings, the A4J campaign director until recently, has tracked and lobbied the bill for the last few years. After it passed the House in February, she said, the bill had made the most progress it has ever made to becoming law since its inception nearly seven years ago.

There is still a chance that the ACA bill will make it through the 2022 Congress before the session closes in December. A lot rides on how much constituency support it will get from now until the end of 2022 when the session closes, Jennings said.

Gathering support from states

A4J has been lobbying in key states to get more support for the bill. According to the A4J website, supportive resolutions have been passed in six states (California, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Kentucky and Utah) and six cities (Los Angeles, New York City, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and Seattle).

The ACA bill was first introduced in Congress in 2015. Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota was the first to propose the sweeping bill to ensure automatic citizenship for all international adoptees, irrespective of their age or year of adoption. Other legislative fixes, such as the Child Citizenship Act of 2000, covered only international adoptees who were age 18 or younger at the time the law was adopted. This left a lot of older adoptees out.

Issues associated with lack of citizenship, such as lack of access to medical care and other citizen benefits like Social Security, inability to get student loans, passports, and secure employment, have plagued an estimated tens of thousands of these older international adoptees over their lifetimes. Jennings said that it is not known how many international adoptees are living without citizenship.

South Korea, one of the few governments that tracks the U.S. citizenship of its international adoptees, has reported that there are 18,603 Korean adoptees to the U.S. whose U.S. citizenship was never recorded, Jennings said.

According to Jennings, international adoptees have also reported they have been living with an old “order of deportation.” That is when the country of origin does not accept the deported person because it considers the deportation to be a violation of the person’s human rights, so the adoptee continues to live in the U.S. without citizenship.

“There are people who have been living in the shadows for upwards of 20 years, unable to work legally or to get benefits,” Jennings said, due to orders of deportation, or other irregularities that prevented them from obtaining citizenshiip. The inability to get work and proper medical care cause major problems for adult adoptees when they have been unable to obtain citizenship, she added. “Conditions like diabetes and congenital spinal issues – those are a couple of the examples we know of that folks in our community are dealing with.”

In extreme cases, some adoptees have been deported for felony convictions, such as certain drug charges. Others have been impoverished because they are unable to access crucial support benefits, such as Social Security. As written, the ACA would solve these issues, and bring all the deportees home.

Jang Kim’s dream of citizenship

Jang Kim, 44, of Utah, is one such Korean adoptee for whom the passage of the ACA would mean a significant and immediate improvement for his life. Through connections, he met Korean adoptee Sara Jones last year and joined the campaign in Utah to pass a supporting resolution. As part of the campaign, Jang testified before the Utah legislature during the 2022 session.

Estranged from his adoptive family at age 10 due to his adoptive mother’s severe mental illness, Kim was 18 or 19 when he began to realize that he did not have the correct paperwork to get a driver’s license or to be hired in the conventional way. His asked his adoptive parents for help, but they could not or would not produce the original adoption paperwork. Working with U.S. immigration as a young adult, he determined through Korean Social Services that he had indeed been adopted in Korea by his adoptive parents, but that they had never finalized the adoption in the U.S. Legally, he was stateless.

Jang has made a living in the Salt Lake City area by working for friends and family, and also at conventional jobs by getting paid “under the table,” he explained. It was a situation that led to employers taking advantage of his predicament by underpaying and overworking him. Employed at a custom furniture-making company, he learned carpentry skills over time, and worked his way to the level of a master carpenter but never was paid more than $12/hour. The employers would sometimes announce that the staff was required to do an “all-nighter” to get jobs finished on deadline, he added.

On his own, he worked with federal immigration officials, and eventually achieved permanent residency status. There were a lot of process complications – sometimes the officials did not even know how to handle his situation, he said.

Kim eventually obtained a green card, but lost it when his wallet was stolen. That resulted in his having to begin the permanent residency process all over again. It was incredibly frustrating, he said. “As a green card holder, you can get things like a Social Security card and a [driver’s] license. But if you lose it, you can’t just get replacements of all your credentials like citizens can. …Even if you have a record of it and lose the physical green card, they will make you go through the entire permanent residency application process all over again. That put me in a tough spot because when lost my green card, I was really back to square one.”

The main advantage to citizenship would be simply a practical one – to be able to have all his documents, and never have to worry about things getting lost and having to start the process all over again. He would have a status that could never be taken away.

So far in his life, Jang said, he has not been able to think beyond the practical very often. Making a living and affording a place to live took up nearly all his time and energy. Recently, the idea of life as a citizen is beginning to fuel his imagination. He has never left the country, and has only been outside Utah twice in his life. Citizenship would mean not only access to jobs at a liveable wage, but a passport, and possibly the chance to travel to foreign countries for the first time.

Jang is a photographer, and likes to take photos of street life. Doing photography on the streets of Seoul and Tokyo is a dream that could be within reach soon. Citizenship would “give me the motivation and self-worth to strive for some other things too,” he said.

Sara Jones and the Korean adoptee-led Utah campaign

Sara Jones said she got fired up to do her part for the ACA in her home state of Utah when she heard through NAKASEC that the bill had passed the house but was having trouble with conservatives in the Senate. Utah bills itself as conservative, but also as family-friendly. Jones led a coalition of state leaders and community advocates to successfully pass a concurrent resolution (passed by House and Senate, and signed by the governor) in favor of the ACA.

In her career of leading workforce development projects, Jones, a Korean adoptee, has met and worked with many of the industry leaders in the state, as well as with many Korean adoptee leaders. In gathering her coalition, she strategized that the ACA could be framed as a way to support families and also the future workforce of the state.

One of the co-sponsors was Sen. Jani Iwamoto (D) the first Asian American woman elected to public office in the state, now retired; the other was Rep. Robert Spendlove (R), who also works for Zions Bank and approached the citizenship campaign as a way to cure a workforce issue for the state. She also asked for and got support from some prominent Korean adoptee community leaders in Utah.

Jones said their group’s strategy was that the adoptee citizenship issue is an economic one. “That was something I really pressed on,” she said. “A lot of people assign it as a family or immigration issue, and some people have asked me ‘well why is it an economic issue?’ And I just asked ‘have you ever led your life without citizenship in America?’ It affects everything. It’s a limit to resources, and access to capital and your livelihood… It was so interesting how many policy makers did not understand that. It’s because they take their citizenship for granted.”

Building ACA support in Iowa

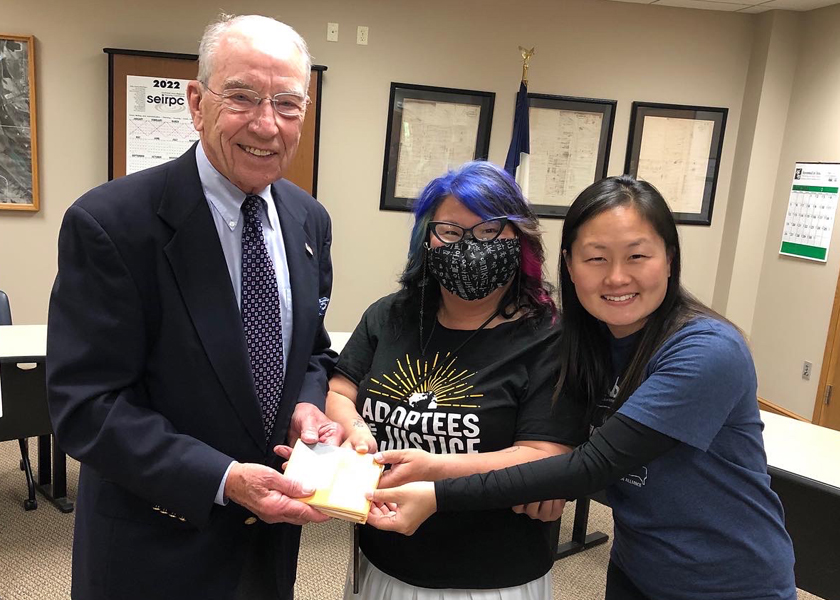

Jennings said she participated in three trips this spring and early summer to build constituent support in favor of the ACA. The idea was to send a message to U.S. Sen. Charles Grassley, ranking member of the Senate, that his state favors citizenship for all adoptees. During the summer Iowa actions, more than 300 postcards were hand-delivered at one meeting with the senator. Nine Asian American immigrants along with faith leaders wrote a coalition letter of support to Grassley. A public meeting was held with the sponsorship of the Iowa Asian American-Pacific Islander Commission, and A4J supporters also talked to participants in the Asian American Festival, CelebrAsian, held in Des Moines in late May. Iowans were overwhelmingly positive and in favor of the bill, Jennings said.

An Iowa Korean adoptee group held constituent meetings with Grassley’s office and, members wrote two op-eds about the topic, Jennings said. One Iowa Korean adoptee went to the town hall constituents’ meeting sponsored by the Asian American commission, and talked to Grassley directly about it, she added.

As a group, Republicans have been in favor of stricter immigration. The lobbying trips in the name of A4J, with support and sponsorship from local organizations, was to persuade Iowans, and through them, to persuade Sen. Grassley, that adoptees were always intended to be citizens, and that their lack of citizenship is due to a legislative oversight. Although Iowans have been receptive “the reality is that there is a conservative camp of the Senate that simply do not want to expand citizenship rights to anyone,” Jennings said.

Facing up to the injustice to adoptees

To fix the citizenship issue for the adult adoptees who were left out of the poorly-conceived Child Citizenship Act is also “an admission that adoptees were wronged, and to face up to the fact that laws on the books are unjust to a whole age group of international adoptees,” Jennings said.

There are still some legislators, among them Sen. Grassley, Jennings explained, who voted for the existing Child Citizenship Act (passed in 2000). A4J has been pushing the agenda that Congress now has an opportunity to repair this legislative oversight that has been a source of hardship for thousands of international adoptees.

“It is not super surprising that we would be facing a lot of barriers,” Jennings observed. “From our perspective, it’s not anything our community has done. It’s the brokenness baked into our adoption and immigration systems, and we’re asking for it to be fixed, and that there’s a level of taking ownership at a systemic level that is kind of hard [for some legislators] to do.”

Although the Adoptee Citizenship legislation has the potential to improve the lives of tens of thousands of international adoptees, it is considered a small bill when compared to many others in terms of the numbers of people affected, she explained. The bill will be in the Senate to be voted on this fall, possibly as a stand-alone bill, and possibly as a part of another bill. It is standard practice to make the smaller bills parts of larger bills, according to Jennings.

“Our bill has wide bipartisan support, and we think it has the best chance in these broader bill packages of passing.” In the end, Jennings said “It does not matter if it is passed as a stand-alone or part of a larger bill – we only want to see it pass.”

Constituency support for the Adoptee Citizenship Act is crucial right now. Adoptees for Justice has a form to fill in for a letter of support to national elected officials at this link https://www.adopteesforjustice.org/take-action/