The Walker Art Center celebrates Parasite director’s Oscar win and reviews his body of work | Feature by Song Un Lee (Spring 2020 issue)

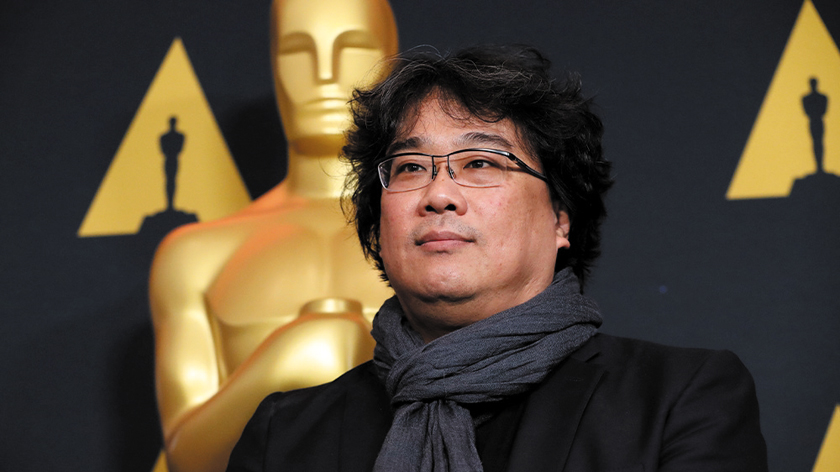

After the historic 2020 Oscar night in Los Angeles, where acclaimed film director Joon Ho Bong won for best original screenplay, best international feature film, best director and then the dizzyingly euphoric prize for best picture, he barely had time to drink and party with his Parasite posse before getting on a plane to Minneapolis a day or so later to attend a Parasite screening and Q and A interview event at the Walker Art Center, the last in a series events entitled Bong Joon Ho: Beyond Boundaries, which included screenings some of Bong’s work.

The event, held February 12, was moderated by Scott Foundas, former chief film critic for Variety and current Amazon Studio executive and, according to Bong, an old friend of his. Foundas wisely avoided asking too many Parasite questions as Bong was probably exhausted from the Parasite Oscar campaign that started in August and culminated in its Best Picture win in February.

Bong reveals key past experiences

Instead, the topics were mainly Bong’s previous films, his youth and his days as a young aspiring filmmaker. One memorable part of the interview was Bong’s recollection of his childhood as a third grader in Seoul. His class consisted of kids from all economic and social statuses. Bong grew up in a comfortable middle-class family and he noticed the poor kids had a distinct smell to them, due to the barely makeshift homes they came from. He befriended one of them and, as a friendly gesture, decided to include him in an activity with his other middle-class friends. These friends made it clear to the poor kid that he did not belong there and Bong felt terrible for putting his friend in that situation.

That experience prompted Bong to think about the lines that divide the economic classes and the whys and hows that create class boundaries. This recollection was very telling, as Bong’s films either subtly or explicitly depict economic class spectrums, and especially the gradations within the classes. The story illuminated the reasons for Bong’s frequent portrayals of mentally-challenged characters who are often exploited by people in a lower-class environment.

Bong has made seven films including his debut Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000). His career trajectory aligns with the general rise of Korean cinema both domestically and internationally. Shiri (1999), directed by Je-gyu Kang, was Korea’s first home-grown blockbuster. Prior to Shiri, American or other foreign films always topped the box office in Korea. Then came JSA (2000) (directed by Chan-wook Park) and My Sassy Girl (2001) (directed by Jae-yong Kwak). These and few other Korean films kicked off the rise of Korean cinema in the greater global film audience.

Bong’s debut feature bombed at the box office at the time, so it’s ironic that among his Korean colleagues, he would be the one to rise to the top, 20 years later. Below are some thoughts on Bong’s films and how his themes and styles have developed over the years.

Black comedy reveals Bong themes

Bong’s first film was Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000, or Dog of Flanders). I remember watching the Japanese-animated TV series of the same name growing up in Korea. I mostly remember the cheery, catchy theme song, so seeing the title brought back childhood nostalgia. Alas it’s an ironic title as the movie depicts characters who despise and attempt to kill and/or eat dogs and a young woman’s mission to rescue these canines.

It’s set in a large apartment complex in Seoul where technically dogs are not allowed, but the rule is not enforced. Those who want to enforce it are mainly driven by the annoyance of the constant, high-pitch yelping.

This black comedy stars perhaps my favorite Korean actress, Doona Bae (who later appears in Bong’s The Host). She plays a lovable loser, the first in a series of loser characters who appear in Bong’s films. Although she is none too bright, she is driven to find and rescue these missing dogs. This is contrasted with a young couple in the apartment complex where the out-of-work graduate student husband (the dog killer) also feels like a loser because all his contemporaries are leaping over him professionally and he is unable to provide for his pregnant wife. His only potential solution is to scrounge up $10,000 to bribe the school’s dean in hopes of obtaining a professorship.

From Bong’s interview at the Walker Art Center, he outright instructs the audience to avoid this film (half-jokingly of course), and the movie does feel like a rough draft. One of Bong’s strengths is his tight, finely-tuned screenplays, and this film does display some nice twists and turns but it also has meandering tangential asides (like Godard and Scorsese’s early works). More than any of his other films, including Parasite, this film feels most Korean, for lack of a better word, in its vivid depiction of contemporary urban anxiety and the sense of longing to step off the hustle of the dog-eat-dog world to take in the beauty of the motherland’s nature. It also features a wonderfully kooky performance by Bae.

A police drama – Bong’s best work?

Memories of Murder (2003) is Bong’s first film with Kang Ho Song, who will become his favorite go-to leading man. Based on a true story from the ‘80s, Song plays a none-too-bright country detective burdened with finding a serial rapist/killer in his town. His captain, realizing Song might need someone smarter to assist him, calls on a cop from Seoul to help with the case. It is the uneasy, sometimes volatile relationship between the two detectives that is at the heart of the film.

In terms of craftmanship, Memories is definitely an improvement over the rough draft feel of Barking Dogs Never Bite. Yet, unlike Barking, which seems wholly original in concept, this is a police procedural genre film. Song plays Bong’s lovable loser character with humor and humanity. At the same time, Bong isn’t afraid to depict cops brutalizing their suspects in the interrogation room. Bong also introduces a mentally-challenged character who becomes one of the murder suspects. The theme of how the powerless are made society’s scapegoats will appear again in Bong’s later film, The Mother. This film demonstrates Bong’s growing confidence and skill as a filmmaker and storyteller, and many have claimed this to be his best work.

When the monster is us

In The Host (2006), Bong mines the Han River and comes up with his first monster movie. It became the number one box office film of 2006 in Korea and also found success in the U.S. as well. Kang Ho Song once again plays a lazy, loser father of a daughter who has been captured by the monster. Doona Bae shows up again as Song’s aspiring Olympic archer sister.

The monster is a result of the American military dumping chemical waste into the Han River. The U.S. dumping of poisonous waste into the river is unfortunately a real incident that happened in 2000, when the U.S. military dumped formaldehyde into the river. As in other creature films, the villain is not only the monster, but also the U.S. military that has spawned the creature.

Bong never lets the scope of the film get out of hand, and is able to find humor and goofiness amidst drama and action. There are also scenes of citizens in quarantine as they fear the monster may be spreading a deadly virus. This was few years after the SARS epidemic was still fresh in everyone’s mind. These days, it is a reminder to Americans that the current COVID-19 spread is not the first viral pandemic Korea has had to live through. The film is at its best when the rag-tag family risk their lives to confront the monster head on. It’s funny and exciting and the daughter turns out to be more than just a helpless damsel in distress.

With this film, Bong flexes his action adventure, sci-fi muscle and firmly established himself as a successful commercial filmmaker who can tackle big-budget action films without losing his humanity and humor. The size and scope of the action will be even greater in Bong’s later film, Snowpiercer.

Devoted mom turns ruthless fixer

The Mother (2009) was released three years after the special-effects-heavy monster film The Host. Smaller in scope, this film explores the dark recess of the human psyche by examining a mother-son relationship set in a small village in Korea. Hye-ja Kim plays the title character. Bong made the film specifically for Kim, because she is considered “The Nation’s Mother,” by Koreans, having played many nurturing mother characters in films and K-dramas.

In the film, Kim, as the mother, lives in a constant state of anxiety over her son’s well-being. He is age 27, but appears to have a mental capacity of a child. Bong masterfully conveys this anxiety in a tunnel vision point-of-view shot of the mother looking out her door to keep an eye on her son. As the camera slowly zooms in, we wait in fear until the mother’s anxiety is realized.

By this point in his career, Bong’s staging of actors and his fluid camera movements are in top form. Interestingly, the director decides to move the camera less and use widescreen camera to express this personal story full of close-up shots. There are certain similarities of this film with Bong’s earlier Memories of Murder. Both films are about murder of young women and the subsequent small-town hysteria. Both films also suggest that finding a scapegoat to alleviate the hysteria is more important than seeking the truth. The story points out how the weak and the powerless are often scapegoated since they are unable to defend themselves.

Bong’s trademark humor is toned down here but the main laughs come from the town’s sought-after criminal attorney. His arrogance and affectations are hilarious. But ultimately the film is about the mother’s love for her son and how that love can turn twisted and obsessive when taken to its dark extreme. It is a testament to the film’s greatness that Bong doesn’t resort to voice-overs when conveying the mother’s thoughts. This is his most emotionally powerful and assured film because of his brilliance at visually conveying the psychological turmoil that burns within the heart of the mother.

With the success of The Host and critical acclaim of The Mother, Bong had the budget and the international cast to make Snowpiercer (2013), a legitimate action/sci-fi film. Based on a French graphic novel, it is an apocalyptic film about the last remaining survivors on earth, travelling in a high-speed train that endlessly loops the earth, similar to the earth’s annual rotation around the sun. The tail of the train is made up of the poor and the wretched, and the head of the train houses the wealthy and the elite. Chris Evans lives at the tail and is the second in command of a resistance movement, biding his time to make a move and spark a violent revolution to topple the head. John Hurt and Octavia Spencer also appear as resistance fighters.

On paper this all sounds far-fetched and ridiculous. It’s a credit to Bong’s mastery of his craft that he’s able to create a fully-realized train universe/society given the absurd scenario. He makes bold, expressionistic choices and most of them pay off beautifully. Because it is a graphic novel, he does not strive for realism in the film’s style.

Tilda Swinton plays the klutzy, sniveling villain and her over-the-top performance is great fun. Kang Ho Song appears again in the film but his trademark humor and looseness are missing. Once the revolution gets underway, the film moves with a kinetic force from one train car to the next, and Bong’s dream-like, Lynchian imagery is unlike anything he has done in his previous films.

Admittedly, this is Bong’s first film using previous source material for the screenplay so the credit should be given to Jacques Lob and Jean-Marc Rochette for creating their novel, Le Transperceneige. Bong enlisted Kelly Masterson to help with the screenplay and especially the English-speaking characters. This film is in some ways a precursor to Parasite, because some of the cars toward the head of the train contain visual elements which are like the Parks’ wealthy home in Parasite.

Okja spins the moral compass

Bong returned to original storytelling with Okja, in 2017, a wonderful and hard-to-categorize film about a near-future world where a large agrichemical corporation develops a new breed of farm animals to be slaughtered for mass consumption. A young farm girl who lives with her grandfather (Hee-bong Byun, grandfather from The Host and a Bong regular), develops a beautiful friendship with Okja, one of the genetically-bred animals. When the corporation comes and takes Okja away, she goes on a mission to bring him back to her farm.

Early idyllic scenes of the girl playing with Okja in the lush green mountainside are truly gorgeous. Bong conveys a natural world of innocence and beauty between the two. This natural life was what the characters in Barking Dogs Never Bite were longing and aching for. Tilda Swinton appears again as a self-doubting, neurotic head of the corporation, and again her unique characterization is overacting at its finest.

In this film, the dim-witted, loser characters, staples in almost all Bong’s films, are the villains like Swinton. Jake Gyllenhaal is unrecognizable as a hot-headed sell-out spokesperson for the corporation, who was once an animal lover. Paul Dano and Steve Yeun show up as animal rights activists who form an unlikely allegiance with the farm girl to rescue Okja.

As opposed to The Host, this is a whimsical monster movie, similar to My Neighbor Totoro, except in this case Totoro is bred and slaughtered for his delicious pork chops. The reunion between the girl and Okja towards the end is extremely heartwarming. With Okja and Snowpiercer, Bong has successfully made a leap from domestic to international filmmaking with the skilled and talented help of Swinton and his English writing partner Jon Ronson.

Parasite weaves a tale of class warfare

Finally, after two consecutive international production films, Bong returned home to make this smaller scale comedy/thriller Parasite, released in 2019. Kang Ho Song once again plays Bong’s quintessential lovable loser who cannot seem to get anything going financially. His wife, once a silver medalist hammer thrower, is losing patience, and their daughter and son have practically given up any hope of entering a university due to the family’s poverty and their individual failures to earn sufficient scores on standardized college entrance exams.

Through connection, charm, and deceit, the son lands a home tutoring job for a wealthy family, the Parks. Soon he is able to convince the good-natured but gullible Parks to hire the rest of his family members, the Kims, to work in their home, without revealing that they are all related.

The daughter, played by So-dam Park is a rarity in a Bong film. She doesn’t display typical loser traits. She is clever and calculating. She probably would have found success if she had not been born into poverty. There is a telling scene when the family is getting drunk in the Parks’ home, celebrating their infiltration into the Park family, when the father character expresses sympathy toward the former maid and the former chauffeur. They were both fired after the Kims made up lies about them in order to take their places in the household. The daughter quickly rebukes her father for even entertaining those feelings. We’re the ones who need the help, she tells her father, “Worry about us, okay? Come on, dad! Just focus on us, okay? On us! Not driver Yoon but me, please!”

The mother observes that rich people have the luxury of being nice and kind-hearted, while the poor must fight for whatever scarce crumbs of resources that are thrown their way. Bong realizes that it would be dishonest to portray his lovable losers as being able to overcome adversity and succeed by staying lovable. The story points out that the harsh world doesn’t reward the poor for their honesty and integrity.

Bong shows in Barking Dogs Never Bite, you have to bribe the school dean, and in the case of Parasite, lie to the wealthy family and concoct elaborate false pretenses to get the other house workers fired. And (spoiler alert) in the film The Mother, the main character must commit murder and cover up the evidence so that her son can maintain his freedom and not return to prison. Only when the lovable loser stops being lovable, ignores her moral compass and does whatever it takes to succeed, can she be a winner in the eyes of society.

Parasite is a smart, supremely entertaining film with hilarious set pieces and a screenplay that reveals one delightful surprise after another. Yet ultimately, it is a melancholy film about unbreakable lines that divide economic classes, and, in the words of Mason (Swinton’s villainous bureaucratic character in Snowpiercer) “When the foot seeks the place of the head, the sacred line is crossed. Know your place. Keep your place. Be a shoe.”

Bong’s films can be found on DVD or online: Barking Dogs Never Bite (Amazon Prime); Memories of Murder (itunes); The Host (Amazon Prime and Youtube); The Mother (Amazon Prime); Snowpiercer (Netflix and Amazon Prime); Okja (Netflix); Parasite (Amazon Prime and Youtube).

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.