Team publishes 100-year-old eyewitness account of the Korean Independence Movement | By Jennifer Arndt-Johns (Fall 2021 issue)

The history of the Korean Independence Movement and the effort of the Korean people, through non-violent resistance, to rise up against Japanese colonial rule in the early 1900s, is one that remains relatively unfamiliar to most people.

Even among those who are familiar with the movement, many are not aware of the events leading up to March 1, 1919, the beginning of the peaceful uprising in which some 20 million Korean people participated, and for which many thousands sacrificed their lives.

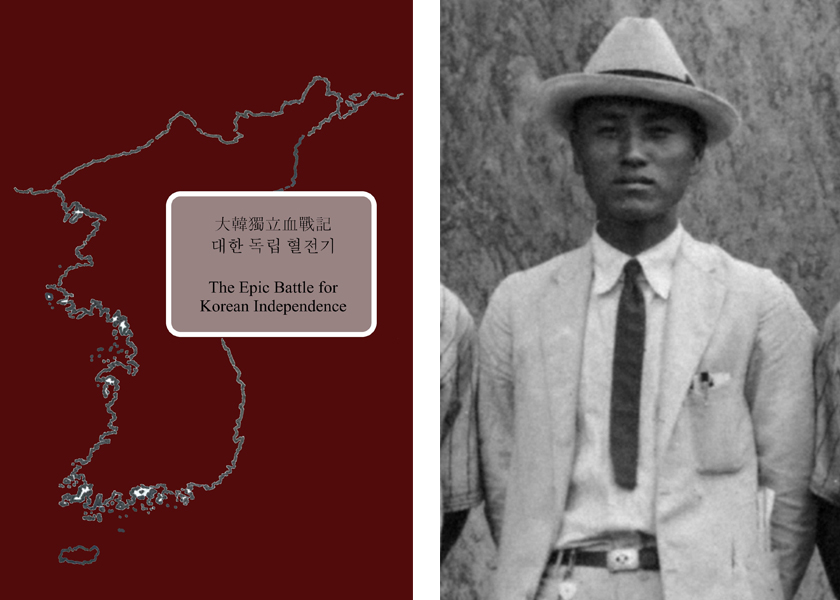

Eyewitness accounts of key moments in history are the rarest of all historical accounts, yet one such history is detailed in a first-time English language translation of The Epic Battle for Korean Independence. This is a newly-translated book, originally published in 1919 in Korean. The book’s English translation was stewarded and managed by University of Hawaii-Hilo Prof. Seri Luangphinith, who was invited by the author’s descendants in Hawaii to translate the account and publish the book online.

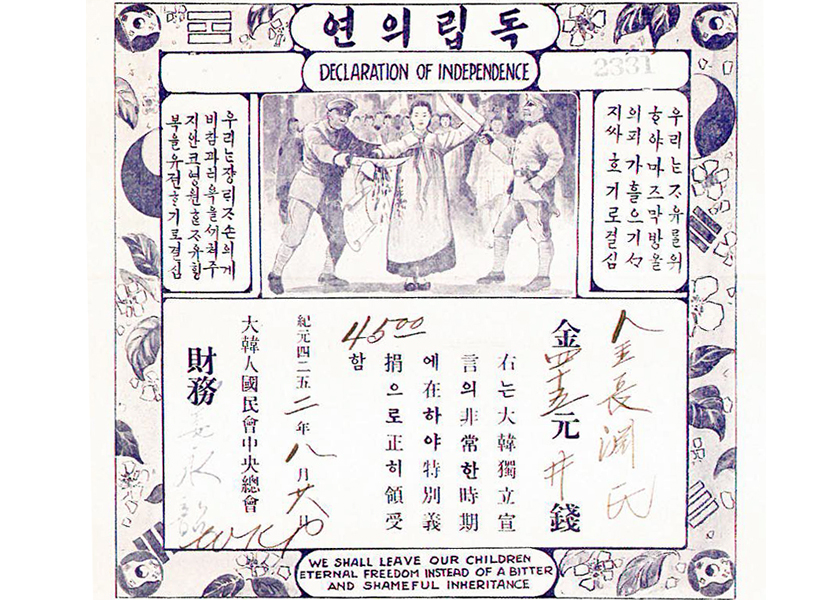

The author, Young Wo Kim, served as the chief financial officer and secretary of the Korean National Association in Honolulu. In this position, he managed and oversaw bond sales that helped fund the efforts of the independence movement in Korea. This book was his attempt to create a historical record of the time.

This feature story marks the official launch of this unprecedented historical account in its online form, an honor conferred to Korean Quarterly by editor Luangphinith of Ka Noio ʻAʻe ʻAle Press at the University of Hawaii-Hilo.

Luangphinith’s interest in the Korean history on the Big Island goes back to before 2017, when she worked with colleagues to host an exhibition by Hye Kyung Seo, a South Korean calligrapher. Luangphinith was responsible for the research related to Korean history on the Big Island to provide in a short handout for the exhibition, she said. “But little did we know that research would turn up so much archival material and personal stories that we were ultimately able to publish a book in 2018,” she said. That book was The Paths We Cross: The Lives and Legacies of Koreans on the Big Island (review in KQ, Summer 2021 issue)

The Paths We Cross attracted a lot of local attention, the editor explained, “and that’s when the family of Young Wo Kim stepped forward with his [The Epic Battle for Korean Independence] manuscript from 1919. No one in the family could read the book since it’s [written] in very, very old Hangul, and no one had a clue how important the book was,” she related.

Luangphinith said that the book was entrusted to her with caution, as the family had heartfelt concerns. In a recent exchange, they acknowledged the book is a very “important record of history” but shared “…given the complexity of the local community to which we belong [in Hawaii], we didn’t want this to simply demonize Japan and the Japanese people because that is not what [the author] would have wanted…”

“[Young Wo Kim] may have been passionate about independence but he never resorted to ethnocentrism or outright race hate. In fact, his business [in Hawaii] thrived because of local Japanese customers from the plantation, and for that he was always grateful.”

Luangphinith stated the choice was made to share the book “in the hope that I could make it accessible to the newer generations of Korean Americans to ensure the importance of their presence on the Big Island is never lost or forgotten,” she said. She also credits the local Korean American community for being supportive of the project from the beginning.

The editor explained that she initially wanted to do a direct translation of the book, and contacted a colleague Soojung Kim, a professor at Changwon National University in South Korea, for assistance. Digging into the project, the two discovered that the author had used many English language sources in composing his historical account, including newspaper articles, Congressional testimonies, cablegrams, diplomatic memoranda and other contemporaneous sources.

After receiving advice from a researcher, Luangphinith decided to transcribe the sources to the book as originally published, rather than the edited version used by the author. “This way, our readers in the local community and English-speaking regions could see the originals as they appeared in 1919,” she said.

Luangphinith said that the description and historical context of the many events leading up to the movement, which are documented in The Epic Battle for Korean Independence will be of “the most value to Western scholars,” since much of the scholarship about the Korean Independence Movement focuses upon the March First Movement in the region and the Provisional Government created in Shanghai. According to Luangphinith, there were “many different groups calling themselves the ‘de facto’ government of Korea, and it is important not to forget the ideas and ideals they stood for.”

Also included are “the first direct English translations of Kim Young Wo’s Preface, the Manifesto from Siberia, and two key eyewitness reports by women.” She pointed out that often the contributions and roles that women played in this history are overlooked.

Luangphinith said that the book is significant because it “captured a specific moment in time, when the fight for independence was just beginning, and there was so much promise with the potential collaboration among a wide group of remarkable individuals… because the book includes all of these individuals, one can see that the Korean Independence Movement was a transnational endeavor initially spurred on by groups operating in Northern China, Southern Siberia, and Japan.”

She said the book reveals the “tensions between thinkers — whether open armed resistance to Japan was going to succeed, or if pursuing a global public media campaign and foreign diplomacy was the better option.”

When asked what she hoped readers of the book would learn, she mentioned the Joseon-United States Treaty of 1882 and the internal American debate that emerged around how and whether to follow through on the terms of that treaty amidst other world events. The Joseon-United States Treaty of 1882 (also called the Shufeldt Treaty) is recognized as Korea’s first treaty with a Western nation and set in place an understanding between the two nations of mutual friendship and mutual assistance in case of attack. History shows clearly that Korea was not well served by that treaty.

Luangphinith shared that the circumstances of the times were “a heartbreaking reminder of how international politics is not always moral or ethical. She went on, “The book symbolizes the diplomatic attempt to persuade larger nations to intervene against Japan’s incursion into the Peninsula and China, namely via a direct plea to President Wilson to support what he himself proposed in his famous Fourteen Points Declaration, about respecting ‘mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.’ Japan was obviously pursuing its sense of self-interest by the early 1900s.

At that time, Luangphinith said, “with Siberia ceded to the Russians and much of Liaodong Peninsula handed over to the Germans, Japan viewed its actions as a defense against Anglo-European parceling of China, and Japanese diplomats aggressively pursued this line of argument by demanding from the United States and other major Allies (France, England, Italy) those territories in exchange for their official sanctioning of the Treaty of Versailles to formally end World War I.”

Documents included in the book from this time show that the colonization by the Japanese was intended to exploit and subjugate. “President Wilson’s decisions in the face of these circumstances say much about American leadership; the same quandary has since played out time and time again — most recently with the withdrawal from Afghanistan. What we do or, more often, what we choose not to do in the face of ethical and moral dilemma is what we should always try to remember, because the human cost is always huge.”

She also pointed out the book documents how the Japanese operated a system of sexual slavery across Asia at that time. This was the historical origin of the Japanese government’s system of military sexual slavery before and during World War II, which has been decried globally as a war crime.

The book contains graphic accounts of the violence, abuse and torture, as well as graphic images relating to the treatment of the Koreans during this period. It is not for the faint of heart.

Luangphinith and her team went to great lengths to ensure the images were from “verified sources” and stated “even at the time there was a lot of controversy over the authenticity of some of these photos.” There is evidence, she said, that the fact of these atrocities led to the beginning arguments for the League of Nations, which would be tasked to address human rights at a global scale. Unfortunately, it took until after World War II, another sad chapter in history, until this manifested.

The Korean Independence movement occurred in a geopolitical context of the end of World War I, and it is necessary to have knowledge of that history to understand the Independence Movement. Luangphinith wrote protracted introductions and used footnotes to provide that context. Working with constructive criticism from their proofreader and a technical assistant who both had little knowledge of the Korean Independence Movement helped add key historical information into the supporting text, Luangphinith said.

The book is available online free. Luangphinith said “The promise I made to the family of Kim Young Wo is that we would abide by his mantra that politics or political undertakings should never be about personal financial gain. In his time, cults of personality and the use of authority or knowledge for personal gain are what helped to unravel a more unified movement. So to honor his memory, I decided to publish the book online as completely open access so that it could not be sold for profit.” The book is available via the University of Hawai’i-Hilo website for Kanoio ‘A‘e ‘Ale Press. The original Korean manuscript and printed copies are archived at the University of Hawai’i-Hilo.

Writer’s note: In reading the book, it’s not hard to understand the potential it has to be emotionally polarizing. Admittedly, I was overwhelmed and filled with sorrow and shock many times as I read each page. I wondered what lead human beings to be so barbaric, heartless and without conscience. I wept as I read the stories of countless human beings whose lives were violated, destroyed and even ended, simply because they had a desire to be free of oppression. I felt helpless and angry regarding the past wrongs that had been committed. But I also marveled at the courage of the individuals who chose to stand up and speak up in the name of freedom, equity, humanity and decency, even at great risk to their own lives.

The Epic Battle for Korean Independence brought things full circle from my own visit to Seodaemun Prison Hall in Seoul in 2017 (KQ, Fall 2020). The book is like a stone that has been raised and thrown forward once again so that the next generation can connect, learn and understand what our predecessors sacrificed and endured with the hopes of ensuring our freedoms so that we may thrive together.

While this history may be filled with pain, it is a commanding historical testament to the strength and resilience of the Korean people. May we honor the spirit of Young Wo Kim and the lives of all our predecessors. May we have the wisdom to embrace “compassion, forgiveness and fraternity” for each other moving forward in time, as his descendants have done. May the past be acknowledged, respected and understood, but remain in the past so that we may as a people, flourish together in the present.

The Epic Battle for Korean Independence by Young Wo Kim (1919)

English translation published by Ka Noio ʻAʻe ʻAle Press

Hilo (HI), 2021