Seoul adoptee group intervenes for travelers during pandemic upsurge | By Tom McCarthy (Summer 2021 issue)

“I just spoke to the Korean Consulate in Chicago who said that I may be able to get an ‘Isolation Exemption Certificate’ to mitigate the two-week quarantine.”

A staff member of Korean Quarterly, began an email with that sentence on June 3. He was in the midst of coordinating logistics for his editorial trip to Korea. At that point in time, he was vaccinated, we wanted him to be present for some specific office activities, and COVID cases had been stable at around 500 a day and were dropping steadily. Worth a try, surely? Well…

Among the myriad of rules to live by when traveling to Korea, there is a unique set reserved for dealing with the Korean government. Rule number one is that engaging with the bureaucratic apparatus of any given ministry or office can be a perilous endeavor, full of surprises. Our inquiry for KQ began simply enough. From the office of the Global Overseas Adoptees’ Link (GOA’L), we asked Korean Immigration for guidance. This went about as smoothly as we expected after a collective office tally of hundreds of calls to various government agencies this year alone.

Speaking to one immigration officer, we were informed that there is indeed a quarantine exemption for “business travel” or “public interest travel.” Good news. The first immigration officer I spoke to told me that for work-related travel, such as a reporter coming to do some coverage on GOA’L, that GOA’L must (he was certain) submit an application to the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy.

GOA’L is not known for trading or industrializing (nor energizing during this pandemic-plagued year, some might argue). Nonetheless, our overworked Korean staffer, Yoonjin, began looking into the process.

Being ever-diligent, she made her own inquiries. In a development that surprised no one, we were told we had the wrong Ministry; because we do none of the three things that the aforementioned ministry is named for. Therefore, we were told, we should submit an application to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, which our non-governmental organization (NGO) activity falls under.

Rule number two for dealing with bureaucracies is that information given can be official, or it can be an officer’s best guess. Have you heard the joke (by some derivative comedian in the U.S.) about waiting in line at the DMV? The eternity it takes, presumably, is because the staff make sure to check all the boxes and follow the right procedures, which of course takes time.

My experience with Korean bureaucracy, on the other hand, is relatively expedient. Every time I’ve gone to renew my F-4 visa, I spend less time waiting in a metropolis of 25 million than I did at the DMV in a city of 120,000, and the actual appointment takes no more than 10 minutes. When you go to trade your foreign driver’s license for a Korean one (if your country or state is permitted to do so), you could very well spend more time getting to the center than the time you spend to do your business in it. A consequence of Korea’s ppalli ppalli (quick-quick) culture bleeding into government agencies is that information you (perhaps naively) assume to be official may just be what some officer assumes is the correct information. Over and over, I’m reminded that it isn’t their fault; ddong (shit) rolls downhill.

After getting our information straight, we set to work getting documents in order. Filling out the exemption application required him to fill out his personal information as well as a detailed itinerary for every day he would have been quarantined, where he would be staying, and how he would get around (even for exemptees, public transit is prohibited). What did the government mean by “detailed itinerary”? Back on the phone with immigration, a kind officer explained that we needed to outline specific times and activity durations, list all individuals involved, and provide specific location and transportation details. Being wise to the system, our office staff made follow-up inquiries just to double check, and sure enough we were told by the application handlers that we just needed basic information like general time estimates, the main people or group that would be there, and roughly where it would occur.

Rule number three is that even though ddong rolls downhill, the individual officers have a lot of autonomy in deciding how much (or little) to rub in your face. This usually manifests itself in deadline leeway or fine reductions. In 2016, I confidently returned to immigration to renew my F-4 for the first time. Lo and behold, the date on my card had worn off and I had missed my renewal date by one day. I began sweating bullets as I recalled the stories of other adoptees and expats who had paid upwards of $1,000 for this infraction (for which the maximum fine is roughly $1,300).

“You are late. The fine is one hundred and fifty thousand won (about $130),” the immigration officer said. I was certain I misheard.

“150,000 won?” I asked skeptically, certain that the number was wrong.

“Yes, 150,000. You must go buy stamps and come back. I will wait,” the officer said. The faintest smile broke out across her face as she saw me begin to understand how big of a break she was cutting me.

With KQ, we weren’t so lucky. Conflicting information between the U.S. consulate and the relevant agencies here in Korea cost us several days. Eventually, we were able to get documents submitted in time for his departure, but in the end, it was irrelevant. Within a day of submitting the application, Yoonjin received a call informing us that the ministry was fairly confident that the application would be rejected because the nature of the business did not appear “urgent.”

This was no doubt compounded by the fact that by the end of June, Korea saw a 200-a-day jump in cases, averaging around 700 daily as a result of lax social distancing compliance by pandemic-fatigued citizens. The government was continuously warning that such an apathetic attitude would lead to a spike in cases. No one seemed to anticipate what was coming mere weeks later.

As he prepared to depart for Korea a week into July and braced himself for the two-week quarantine, daily cases exploded, approaching 1,400 by the time he landed. The Delta variant was spreading. Exacerbating this eruption was almost certainly the fact that a week prior, the government announced plans to lower the social distancing level in an attempt to restore normalcy in time for summer. People couldn’t wait and Korea experienced a nearly 250 percent increase in cases in two weeks. Two weeks after that, despite the government implementing the highest-ever social distancing rules, Korea reached an all-time record high of 1,784 cases.

How did this happen? Well, ddong rolls downhill…

When the government announced their vaccination rollout, it was abundantly clear that the upper echelons of federal and metropolitan logistics designed the plan from the top down; aim for nationwide vaccination as quickly as possible and then expect provinces, cities, and districts to figure out how to make it happen. The policies and plans seemed to change weekly in June and July as the government attempted to staunch the bleeding. The ever-changing directives resulted in administrative chaos and inevitable delays.

This became blatantly evident for many adoptees as Seoul attempted to get all people in certain economic sectors vaccinated, including expat language teachers. In the middle of July, the city announced that all instructors, Korean nationals and foreigners alike, would be signed up for vaccines by district. That was about all the city did, then left it up to the districts to sort out. As people attempted to comply, districts claimed to follow a unique set of guidelines. Some districts claimed that they didn’t have enough vaccines to accommodate both nationals and foreigners eligible for shots and referred inquirers to other districts. Others claimed that their list of applicants was lost and foreigners would have to reapply.

At the time of writing, the situation has still not been completely resolved, as foreigners online report the gamut of results after attempting to get vaccinated. All the anecdotes, however, share a singular connotation; while some administrative employees people dealt with were curt, others were very helpful, but no one had all the details. Everyone was just trying to do their job with the information they had.

Rule number four is to remember that almost all officers and bureaucrats you come into contact with are trying their best to do their job correctly and efficiently, often in a second language in their own country. While it may feel therapeutic to blame the front-line workers, it is evident time and again that they have been left to sort out the details on their own, as is often the case with ministries and agencies like the CDC, immigration, or district offices.

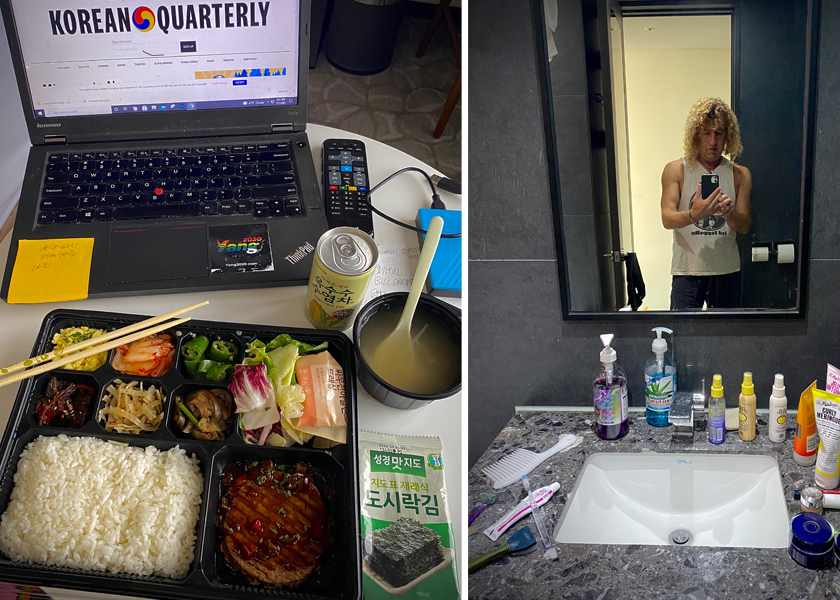

The KQ staff member successfully survived his quarantine. Currently, the quarantine policy is still in effect, and exemptions are hard to come by. The latest exemption policy piqued the interest of many adoptees as it permits “overseas Koreans” to visit parents or grandparents (yes, they are this specific) without quarantining. However, this policy requires specific proof of a familial relationship; the official family registry. The number of adoptees on their family’s registry could likely fill no more than a small charter plane, and it is very difficult to be added. For now, adoptees have to wait until this outbreak subsides for a policy change.

The intent of this piece is not to imbue anyone with crippling apprehension before they go toe to toe with a governmental department; rather, the intent is to provide you with a sense of understanding as you attempt to determine what is official and what is a recommendation, what is normal and what is an anomaly.

Ultimately, it all comes down to rule number five: Hope for the best, plan for the worst, but always look on the bright side… You’re in Korea.

.