AdopteeHub in Minnesota and GOA’L in Korea launch collaboration for search and post-reunion services | By Martha Vickery (Summer 2024)

July will be the launch of a new birth search portal by the Twin Cities-based, adoptee-run organization AdopteeHub. The portal will be a key part of a birth search service that is the first of its kind in the 60-plus year history of international adoption. It will blend technology with expert research, counseling and translation to achieve reunifications of Korean family members with their birth children across the miles and cultures.

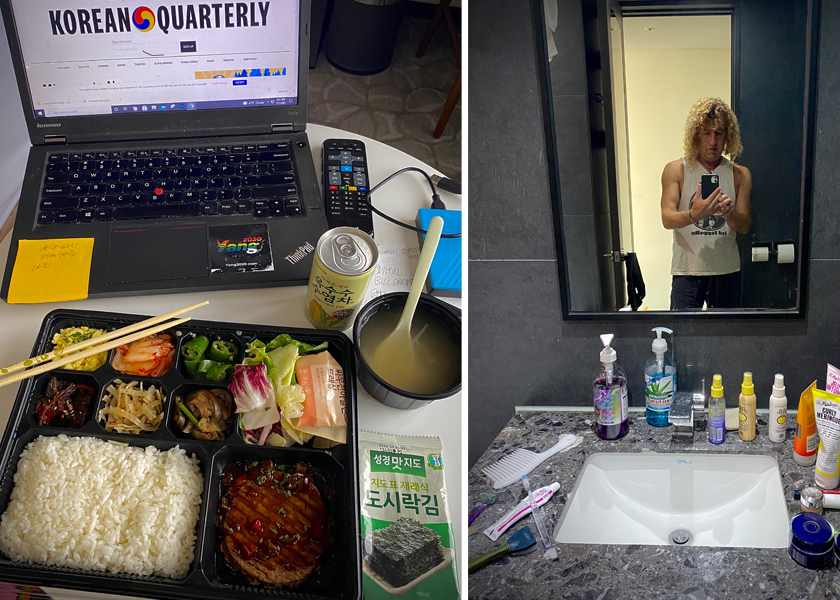

The new database, called the Hope Registry, will be a confidential way for both birth parents in Korea and adult Korean adoptees to enter their personal information as a first step in a birth family search or birth child search. Korean families searching for children they placed for adoption and adult adoptees searching for their original families will get expert assistance to help them in subsequent steps, ideally (but not always) culminating with a family reunion that will be permanent and meaningful.

A bilingual and bicultural approach

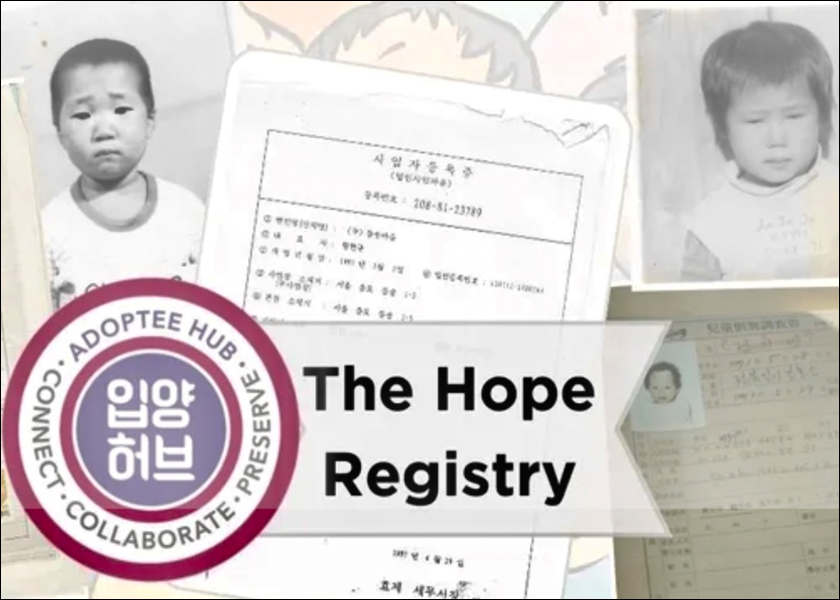

Ami Nafzger, executive director and founder of AdopteeHub, said that their organization is partnering with the Seoul-based non-profit Global Overseas Adoptees’ Link (GOA’L), which she also founded in Korea (in 1998). The two organizations will administer the program in two languages and in two cultures. This joint, bi-cultural approach will allow both native Koreans and Korean adoptees to voluntarily post their own information on the new data base as the first step in the often-complex process of finding birth relatives.

Nafzger visited the GOA’L organization in late May to meet with and train staff who will administer the Hope Registry, the database part of a larger program that will include post-reunion support. Prior to the July launch, she said, she will also train two Minnesota-based staff to help register adult adoptees for the new program. At launch time, set for July, she said, only U.S. Korean adoptees can register. The program will be expanded later to include Korean adoptees living in other countries.

Kara Rickmers, GOA’L’s secretary general since February, met with Nafzger several times during her May trip to GOA’L headquarters. GOA’L welcomed the partnership, Rickmers said, which has been in process for about a year. Right now, she said, adoption agencies do not have a legal way to share information with birth parents about adoptees, and there is no service available to help birth parents search.

The Korean government’s National Center for the Rights of the Child (NCRC) runs a database on which anyone can enter their information, but that database is public, therefore many birth parents and some adoptees are reluctant to use it. The data on it is not actively managed, so it does not work as a staffed search service like the Hope Registry, according to Rickmers.

Under a recent law, adoption agencies were supposed to consolidate adoption records under one service, however, that project was never accomplished, due in part to the agencies’ reluctance to follow the new law. Agencies retain their own information and release adoptees’ files according to their own policies, Nafzger said.

Having lived in Korea and worked with searching adoptees through GOA’L starting in the late ‘90s, Nafzger sees the birth search challenge from both sides. The situation for birth families is unchanged from the situation she observed when she began to do searches in Korea nearly 27 years ago, she noted. In terms of search services, she said, “I’ve talked to a few adoption agencies, and they’ve said there is still nothing for birth families.”

Korean adoptees have had a few more resources available, but there are many deficiencies in search options for adoptees as well, Nafzger observed. Typically, adoptees might put birth search information on social media such as Facebook, which is problematic. She said of Facebook “All the viewers can see it, it’s not specifically going to the Korean community, and it’s all in English.”

A key ingredient – privacy

Since the mid-1990s, when a large group of Korean adoptees reached adulthood, many have tried to find their birth families in various ways. They have used newspaper advertising, appeared on popular morning TV shows in Korea that feature people looking for lost friends and family, employed detectives, and used a DNA database maintained by South Korea law enforcement. Sometimes, adoption agencies or other organizations offering homeland tours to Korean adoptees supply staff who assist in birth searches while tour participants are in South Korea.

The disadvantage of many of these methods is that birth families and adoptees must be willing to go public with their search, which can be a negative and intimidating experience. None supply follow-up for adoptees in the important post-reunion phase of the journey.

In contrast, she explained, the Hope Registry database will be in both English and Korean, and the information entered by the users is confidential. Only basic information, approved by the user, such as a name and a photo, will be available for viewing by other registered users on the portal. Each participant will enter more details, however, that information will be only for viewing and use by the staff working confidentially to match participants with family members.

Funding a labor-intensive project

Entering information on the database is only the initial step in part of an overall program that combines technology, data and guidance. The researchers find key information or ask the participant for more information “because the more information we can gather, the better a chance for a match,” Nafzger said.

Many adoptees have already entered their names and information on GOA’L’s database. GOA’L database enrollees will need to separately enroll with the Hope Registry, although information on the GOA’L database will be used by staff as one of the search resources, Nafzger said.

Because of one anonymous major donor, the start-up costs for the program are covered. Participants will be able to register for $30. Another donor, the Thomas and Wonsoon Foundation, funded by Korean adoptee and entrepreneurial inventor Thomas Park Clement and his wife, artist Wonsoon Kim, will supply the funding for DNA matching of birth parents and adoptees, and will also support the post-reunification program. This grant will make the DNA test free for program participants.

Success of the program will depend on sourcing more funding and getting ongoing support from donors who are on board.

Preparing for anything to happen

As a social worker with years of experience in birth search, Nafzger said she favors doing an initial “readiness assessment” for Hope Registry enrollees, possibly a counseling session paired with a questionnaire for all participants, so that adoptees and birth families will be prepared to deal with all the possible outcomes of a search.

Other readiness resources for adoptees, still to be developed, may include examples of stories and/or videos about adoptees who searched and were reunited, or not reunited, or those who searched but were rejected by their birth families, Nafzger said. Through GOA’L, similar resources in Korean will eventually be available for Korean nationals who enroll, she said.

There are no models for AdopteeHub to follow on how to help after a family is reunified -– post-reunion support services will be a new invention. Nafzger observed that “Post-reunion resources are missing. They just don’t exist. And we need to start doing something around those things. Too many adoptees have found families, but then lose contact with them.”

Managing expectations across cultures

Rickmers, who has lived in Korea for six years, and worked with GOA’L for the last four years, noted that there are many search resources available for adoptees, compared to almost none to help a family that is newly in reunion. Beyond the language barrier, she said, there are the larger problems of “the expectations on both sides -– the point of view of the birth family and the adoptee are often very different in terms of what a reunion means to them,” she said. Such expectations “can often lead to miscommunication and suddenly they are no longer speaking and no longer in reunion.”

Back in the ‘90s and early 2000s when Nafzger was finding birth family matches for adoptees who came to her through GOA’L, the organization got a publicity boost through a story in the newspaper Kyung An Ilbo and after that, through a KBS network TV documentary. As a result, several hundred Korean nationals volunteered with GOA’L, mainly to help with birth searches. Because of those native speakers, hundreds of parent-child reunions were achieved, she said. Native Korean volunteers are still essential to GOA’Ls program today.

The GOA’L staff who will work with the Hope Registry are two native Koreans “who have both worked overseas for many years,” Rickmers said, “and they can understand the Korean perspective but can also advocate for the perspective of the adoptee.” Over time, she said, GOA’L will “build up its post-reunion program in a more nuanced way, and work towards a formal reunion support program, with AdopteeHub, including the steps of how to prepare for the reunion, how to negotiate issues, and how to follow-up over time with birth families and adoptees, she added.

GOA’L can also work with birth family members and adoptees when an in-person search is impossible due to either party’s work commitments or financial issues. Services will include translation/interpretation and help in initial meetings and follow-up virtual family meetings.

Rickmers noted that GOA’L has had success in posting printed flyers on bulletin boards and in community centers and marketplaces in a neighborhood where an adoptee was known to have been found. The flyers include a photo and list any relevant information about the adoptee, asking for those with knowledge of that adoptee or their family to come forward.

However, she added, there is a limit to what GOA’L can do by proxy when the adoptee is not in Korea. Also, she said, the response is much more enthusiastic in a community when the adoptee personally shows up with a GOA’L staffer. “When people see this person who has come so far to do this thing, then we can see how the community oftentimes opens up and people will almost bend over backwards to help this person,” she said.

Walking neighborhoods to do birth searches is also a good way to inform Korean nationals about how the Hope Registry works for birth parents. Because some birth parents they search for are elderly, GOA’L will produce information on paper, and allow prospective enrollees to pick up a form in someplace like a community center and mail it into GOA’L, she said.

Nafzger said that use of technology, including virtual calls and social media, along with translation services, counseling and guidance, is another way to enhance and support reunions and for enrollees across the world work on their relationship over time.

Building participation among birth families

Rickmers said another part of GOA’L’s role will be to announce the opening of the registry to the Korean public at the right time, and campaign for it through its own contacts and through the media. It’s essential for the success of the program, she said, that Korean birth parents trust the program and come forward to add their information to it.

Nafzger said she will be discussing the new program with adoption agencies with the objective of achieving their support and will agree to refer birth families to the program when they walk into the agencies seeking information about their adult birth child.

A larger but related issue to persuading the public to use the Hope Registry, Rickmers said, is for Koreans to accept Korean adoptees as members of Korean society. She wonders how best to promote this idea, whether it is getting Korean adoptees to volunteer for causes in the community, to campaign through media, or just break down cultural barriers through people-to-people exchanges. It is a long-term objective, and a societal issue “that goes beyond GOA’L and even beyond adoption,” she said.

Searching for birth family is a personal decision. Nafzger said she expects the energy for the new birth search service and post-reunion support service to build slowly. “I think once some adoptees have done it, others will learn about it and want to do it,” she said. “Other people may need [a birth search] but maybe not now. We want to provide that safe, comfortable environment. We want the resources to be there when they are ready.”