Petition targets laws in both South Korea and the U.S. to enhance search for birth families and secure adoptees’ citizenship | By Martha Vickery (Spring 2025)

Restoring adoptees rights to citizenship in the U.S. and broadening adoptees’ access to birth family information in South Korea is the dual goal of a petition created by two Korean adoptees in partnership with several adoptee-led advocacy organizations.

Two women researched and wrote the petition – Anne Bertelsen and Alice Stephens. By asking Korean-adoptee-led organizations and reviewing past legal obstacles faced by Korean adoptees, they narrowed down and identified the most pressing issues affecting rights of Korean adoptees in both the U.S. and in South Korea.

The petition is now ready to be signed, and on a digital platform sponsored by partner organization Adoptees for Justice (A4J), a lobbying and advocacy program of the National Korean American Service and Education Consortium (NAKASEC) (see the petition here). The petitioners particularly want Korean adoptees and their (U.S. citizen) family members and allies to sign, however, the petition is open to anyone.

Bertelsen and Stephens also researched adoptee organizations that could help the cause. As much as it was important to write an effective petition, how to publicize and drive it forward was also key. “That is why we called on Adoptees for Justice to carry the citizenship piece. And we also contacted Adoptee Hub, which is working on the Hope Registry,” a virtual portal to link searching adoptees with searching birth families in Korea, she said.

In addition to A4J and Adoptee Hub (a Twin Cities-based non-profit), there are three other partner organizations: The International Korean Adoptee Associations (IKAA), a global network of adoptee-led, volunteer driven organizations focused on community building; the Inclusion Initiative, which advocates for adult adoptees and adult former foster care recipients; and Paperslip, which helps with birth searches by Korean adoptees who were adopted through Korean Social Services.

Three other individuals, A.D. Herzel, Jolene Olsen and Zhen E. Remmelsberg are also advocating for and disseminating the petition, according to Stephens.

Two governments to be targeted

Bertelsen said they eventually want tens of thousands of signers. In the U.S. the petition will signal the U.S. government of widespread support for inter-country adoptees’ right of citizenship and demand that citizenship be automatic and retroactive for all inter-country adoptees. A bill addressing automatic citizenship (the Adoptee Citizenship Act (ACA) ) has been introduced in consecutive Congressional sessions in recent years, but never brought to a vote.

In South Korea, the petition will demand expanded access for adoptees to their own birth family’s records. Bertelsen thinks the petition will get attention “The Korean government historically has responded best when it gets pressured, and particularly by the countries it is aligned with or influenced by,” Bertelsen explained.

With guidance from Korean adoptee advocacy organizations, Bertelsen and Stephens crafted a petition about law changes in both the U.S. and South Korea that Korean adoptees want to see.

Both petition creators are Korean adoptees. Bertelsen worked for the Accenture corporation as a managing director where she administered some large digital projects, and prior to that, in political organizing and advocacy. Stephens is a writer whose interest in Korean adoptee issues has led her to connections with a wide variety of organizations and individuals speaking out for adoptee rights.

Finding the key moment to act

The list of what Korean adoptees need most is “quite extensive,” Bertelsen said, “and there can be some disagreements in the community about what to focus on. So we wanted to concentrate on the most universally-desired items, and that would cause the least amount of controversy.”

The two discussed the petition and its possible content for a couple years. It was after the PBS Frontline documentary television news program South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning (in partnership with reporters Tong-hyung Kim and Claire Galofaro from the Associated Press) first aired on September 20, 2024 that Bertelsen and Stephens decided that such a petition would have additional traction among Korean adoptees and their allies because of the heightened community awareness catalyzed by the documentary.

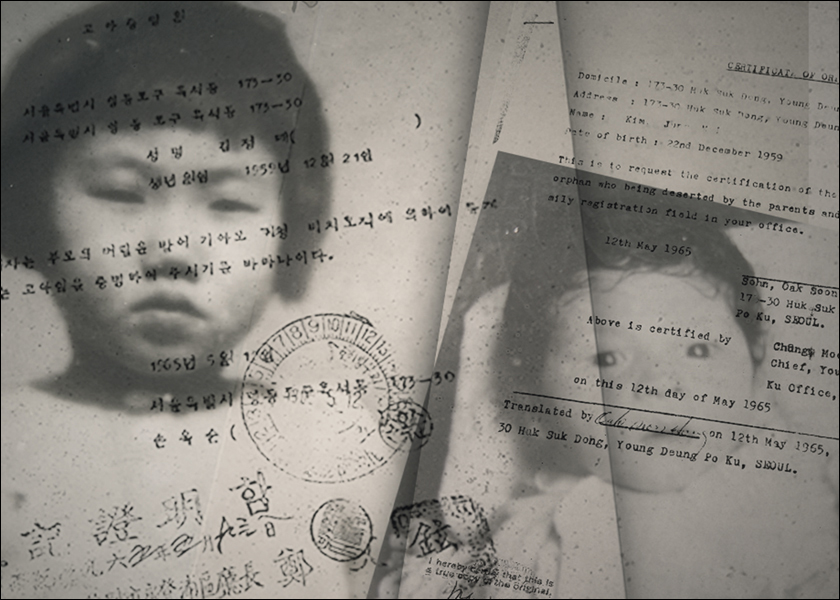

The documentary describes how falsified records were used by South Korean adoption agencies to speed up adoptions in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s, during an era of military dictatorship in South Korea. It suggests that (U.S. and South Korean) regulatory authorities suspected fraud or knew about it, but looked the other way. False records cut off the paper trail, and make it very difficult or impossible for adult adoptees and birth parents to find one another.

Several Korean American adoptees and adoptees from Scandinavian and European countries were interviewed for the documentary, some of whom found family members despite useless records. One of the interviewees was Alice Stephens.

The role of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

The documentary also describes how a group of 53 Danish Korean adoptees filed an application in 2022 to begin an investigation of the apparent fraud through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), an independent body established to investigate human rights abuses (See AP’s 2022 reporting by Tong-hyung Kim here).

Past investigations by the TRC have included offenses by the Japanese Imperial government against the Korean independence movement, mass atrocities of the Korean War and human rights violations during the era of South Korea’s authoritarian rule, according to its website.

The documentary, and previous AP investigative reports by Kim, suggest that there is a widespread incidence of falsified adoption records. Although there is awareness about falsified records among Korean adoptees and their families and Korean international adoption professionals, there has been no official study to investigate the frequency of records falsification. TRC will be the first to formally report on this issue.

The Commission expanded the investigation of the 53 Danish Korean adoptees to 367 adoptees’ cases. Of those, 32 files (or about eight percent) belong to Americans, Bertelsen said, while more than 60 percent of all Korean adoptees are Americans. One of the files belongs to Alice Stephens. The due date for TRC’s final report has been pushed forward a few times. A preliminary report was published in late March.

The TRC report – what to expect

If the final TRC report does turn up widespread fraud in the history of Korean international adoption, will it be a shocker? Not for those most affected, Bertelsen guessed.

“For many of us who have been trying to find our records for a long time, that documentary did not disclose anything new,” Bertelsen said. “Nor will the TRC report drop any bombshells of information on the adoptee community. What I will say about the documentary is that it did raise awareness, particularly for the U.S.-received adoptees, about the fraud.”

Concerning any official response to the TRC report by the South Korean government, Bertelsen said that “based on other work they’ve done, I’m skeptical that they will announce any concrete policy recommendations that will remove the barriers for adoptees to get their information. I think they will respond that ‘there was fraud and we are responsible for that,’ but in terms of what happens after that, I think it will be very little.”

Stories from searching birth parents

Ami Nafzger, director of the Twin Cities-based Adoptee Hub, and founder of the Global Overseas Adoptees’ Link (GOAL) in Seoul in 1997, was called on by the petition organizers to be a subject matter expert about birth family search in Korea. Adoptee Hub is a partner organization in the petition campaign. Nafzger has been working with searching Korean adoptees and searching birth parents since GOAL’s founding.

In January, in cooperation with GOA’L, Adoptee Hub launched its Hope Registry, a confidential digital portal designed to allow Korean adoptees and their birth families in South Korea to search for and connect with one another. The registry began accepting birth family applicants and adoptee applicants in January.

Based on her on-the-ground experience, Nafzger believes the TRC report will turn up a high incidence of falsified records. Working for GOA’L back in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, she explained, birth parents came to her for help searching for an adoptee birth child. Some came to GOA’L because they did not trust the agencies; others came because the adoption agencies turned them away.

From some of these parents, Nafzger said, she heard claims that the adoption agencies took their child against their will – that they had never formally relinquished their child for adoption. She said that some birth parents told her various versions of the same story – leaving a child in an orphanage for a short period of time (because there were no daycare centers) due to some kind of family emergency, and returning to find their child had disappeared, and the agency had some excuse for it. Some parents even went to media with their stories, she said.

According to Nafzger, adoption agencies always had their own policies concerning birth search when either birth parents or adoptees showed up, which makes records searching even more frustrating. “They didn’t have any laws,” she said. “Adoption agencies have said ‘well there are no laws so we can do whatever we want,’ and they did do whatever they wanted. And the Korean government should be blamed for it because they didn’t do anything about it.”

A three-pillar approach

The petition is built on “three pillars” according to Bertelsen. Two of the demands are directed to the South Korean government. One demand is to make birth family searching less cumbersome for adoptees by removing the legal or policy barriers to obtaining their own adoption records, and by expanding access to an adoptee’s records to siblings, cousins, uncles, aunts and grandparents of the adoptee as well as to the U.S.-born children of the adoptee, instead of restricting access to the adoptee and their birth parents.

It also asks the government to make the South Korean DNA database compatible and collaborative with commercial DNA systems Americans use (such as AncestryDNA, My Heritage, 23andMe and FTDNA), which would make DNA matching less expensive and easier.

The second of the three pillars is the demand to appoint Korean adoptees to a board concerning policy about Korean adoptees – the National Commission on the Rights of Children (NCRC). Among other adoption-related matters, the NCRC advises on privacy laws applicable to adopted persons’ birth records, Bertelsen said. The petition also asks for monitoring of and more transparency by the NCRC about its activities.

There have never been any adoptee members of that advisory board, Bertelsen added. The membership at present includes only representatives of adoption agencies. “There’s an organization in Korea for domestic adoption that has applied and also been denied access.”

Pushing for automatic citizenship

The third pillar of the petition, directed at the U.S. government, is to finally make citizenship automatic for the roughly 20,000 Korean adoptees who were not made citizens by their adoptive parents (or guardians) — the figure of 20,000 just a rough estimate because it is from a report from the South Korean government of the number of Korean American adoptees for whom citizenship could not be verified, according to information from the Adoptees for Justice organization.

A law passed in 2000, known as the Child Citizenship Act, created automatic citizenship for international adoptees who were age 18 or younger when the law was passed. According to the Q and A section of the petition, that law excluded about 20,000 Korean adoptees who were older than age 18 when the law was passed. A large group of Vietnamese adoptees who came mainly in the mid-1970s at the end of the Vietnam War were also excluded, Bertelsen said.

A4J has been advocating and lobbying for a bill (the Adoptee Citizenship Act (ACA) ), which has been introduced for consecutive years in Congress since 2015 but never brought to a vote. Upon passage, the law would make citizenship automatic for all international adoptees, therefore it would cover adoptees who are older than the cut-off date of the Child Citizenship Act. It would also cover deportees, and allow them to return as citizens to the U.S.

Notably, the petition also calls on South Korea to refuse to accept Korean adoptees from the U.S. as deportees, since U.S. citizenship was promised to them as a part of the international adoption process.

Not having citizenship robs adoptees of necessary rights, including key forms of identification, such as drivers’ licenses and passports. It also prevents them from accessing crucial federal benefits, including federal student loans, medical assistance, Medicare, and Social Security, among others.

Because non-citizens with felony convictions can be deported, a small number of Korean adoptees have been either deported or are at risk of deportation, due to being non-citizens in combination with a past felony conviction (See KQ coverage of the pardon campaign for Emily Warneke and Judy Van Arsdale here).

Other goals besides better laws

Bertelsen said there are a couple strategies for doing the petition in this way, and at this time. In addition to changing laws, the petitioners want to increase awareness of the legal barriers for Korean adoptees – to U.S. citizenship, and to records access in South Korea.

Bertelsen pointed out that the U.S. crafted the system of international adoption, and bears some responsibility for its flaws that plague searching adoptees today. Part of the petition campaign is to increase awareness of those flaws as experienced by Korean adoptees, and ask for legal relief from them, she explained.

The petitioners also want to make adoptees and allies aware that the NCRC has been directed to consolidate adoption records from all the adoption agencies into one system. How the government will do that is a big unknown.

Item six of the FAQs on the petition states that the records transfer will happen in July 2025, and states that “there has been little public communication about how adoptees will be able to access these records after that transfer.” Adoptees fear that they “could face even greater barriers than they do today,” according to the petition FAQs, and it calls on the government to ensure “transparency and accountability” throughout the records transfer.

Building greater pressure for the Adoptee Citizenship Act (ACA) is another crucial goal. A large quantity of signatures will indicate the support of the electorate. The ACA needs more push – it has never had enough support to bring the bill to a vote. It came closest in 2022, when it was added to the Chips Act, but the ACA portion was stripped from the bill before the vote. A4J had worked for months, lobbying individual states for support, and visiting key conservative states that year to garner support resolutions (see KQ’s coverage of the 2022 lobbying effort here).

A coalition in a big wide country

Although the numbers of adoptees who arrived in the U.S. between the mid-‘50s to mid-‘90s is large (110,000 to 120,000), Bertelsen said, that amount is “a needle in a haystack” compared to the population of the U.S. “In a place like Denmark, the percentage of adoptees compared to the whole population – that number is quite large. So, there’s a bit more awareness and cohesion in that country,” Bertelsen said. Danish adoptees were able to leverage the pressure for a TRC investigation because of better recognition and support for their cause by their country’s government, Bertelsen suggested.

Bertelsen said the petition is designed to get Korean adoptees to speak with one voice about the issues of greatest need to them, she said. “So our work here is also to focus on U.S. adoptees and coalesce them.”

Pushing for the long haul

In addition to building a coalition of support, sustaining the push for the petition is also a key concept. Making law changes is characteristically slow. Therefore, the petition campaign will need sustained energy to be successful.

In the U.S., it is hard for a relatively small population group to get Congressional attention, as A4J has experienced repeatedly with the Adoptee Citizenship Act. With the distractions due to upheaval by the new Trump administration, getting that attention could be even harder in the near term.

To make matters more complicated, no South Korean ambassador has been appointed yet in the new administration, and some State Department officials have been fired, Bertelsen said.

In South Korea, meeting Korean American adoptees’ petition demands could also take some time. Bertelsen said that both modifying privacy laws and requiring representation by adoptees on the NCRC board will require legislation. There is no such bill proposed right now in South Korea – it will need to be written and get support by South Koreans first.

Bertelsen has visited South Korea often in recent years, in part to find allies for better birth records access. There are sympathetic legislators there who would take an interest in the cause, she said. But even with a legislative sponsor, new legislation is a long process.

“Nothing with diplomacy is quick,” she said, “but this is time to act, due to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission investigation, and because of the documentary coming out.”

Although there is no one organization of U.S. Korean adoptees, she said, she is confident in the expertise and reach of their U.S. organizations and IKAA, the one international partner organization. “There are some amazing organizations that are trying to make a difference and focusing on issues they have expertise in and the resources for. That’s terrific and we need that kind of sustained push to do that.”

In addition to the link to the petition, the petition will be introduced and linked on the websites and social media sites of the petition partner organizations. A link for the Frontline documentary “South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning” is here. KQ will update this story for any outreach events or further developments.