The Interrogation Rooms of the Korean War: The Untold History ~ By Monica Kim

(Princeton University Press, Princeton (NJ), 2019, ISBN #978-0-6911-6622-3)

Review by Bill Drucker (Winter 2020 issue)

In 1950, 20-year-old Se-hui Oh was making his way back to Kyongsang province, after serving in the North Korean People’s Army (KPA). A voice shouted for him to raise his hands. Oh saw South Korean soldiers with guns aimed at him. Oh had encountered this situation before: He would often run into either another KPA soldier or a South Korean soldier, or a United Nations Command (UNC) soldier. Oh carried four sets of ID papers. They were essential survival tools of wartime. This time, however, he was not set free. Instead, he was taken into custody and became a prisoner of war.

During the Korean War, there were numerous U.S. and UN prisoner of war (POW) camps. There was one UN Custodian Camp under Indian forces outside of Panmunjom. The U.S.-UN POW camps were located in the southern provinces and the some of the southern islands.

Managing POW life was complicated by overcrowding (one camp swelled to over 170,000). It was like running a small city. There were the logistics of food and supplies, medicine, clothing, shelter, water and sanitation. There were also social, cultural and human rights problems; prisoner social strata, racism and related violence, a lack of Korean or Chinese interpreters, and prison policing issues, among others.

Well researched and written, this detailed war history highlights a forgotten aspect of the Korean War. The author examines the players, the political and military agendas, and the social dynamics of long-term prison life. She does not dwell on the gritty elements of prison life; the deprivation, torture and hunger. Rather, she provides a higher-level look that shows an agenda that is beyond the prisoners and their predicament, which delves into U.S. social and political policies of the time.

The author sets the context by explaining that one major issue after World War II was what to do with Korea. The U.S. and Russia took possession of the country via the military. Kim notes that “Military occupation of a liberated country is basically self-contradictory.” But, as Russian and U.S. leadership came to understand, strategic real estate holdings were very important. The U.S. was already occupying the Philippines and Japan, where it provided post-war aid, western technology and culture, and the example of U.S.-style democracy.

It was an uneasy time in 1945 when the U.S. military bivouacked in South Korea as both occupier and liberator. The period of liberation and self-rule was remarkably short, after which came another imperialistic colonization. General Hodge became the acting military governor of South Korea. It is no secret that Hodge hated his post, and the Koreans equally despised his inept handling of their country.

The tensions of a divided Korea, the occupation of foreigners, the rise of Communism, and other factors created a cauldron of resentment. Hardly a democratic transition, South Korea was a military-controlled state once again. General Hodge, the CIA, the U.S. military and the South Korean military established joint and separate spying networks. Prisons were filled with dissenters, political leftists, and critics of U.S.-Korea policies. Within the U.S. network, Koreans were being labeled friend or enemy. Hearsay could get a person arrested. People were encouraged to fink on their neighbors. The U.S. and South Korean militaries would arm forces to quell large opposition actions.

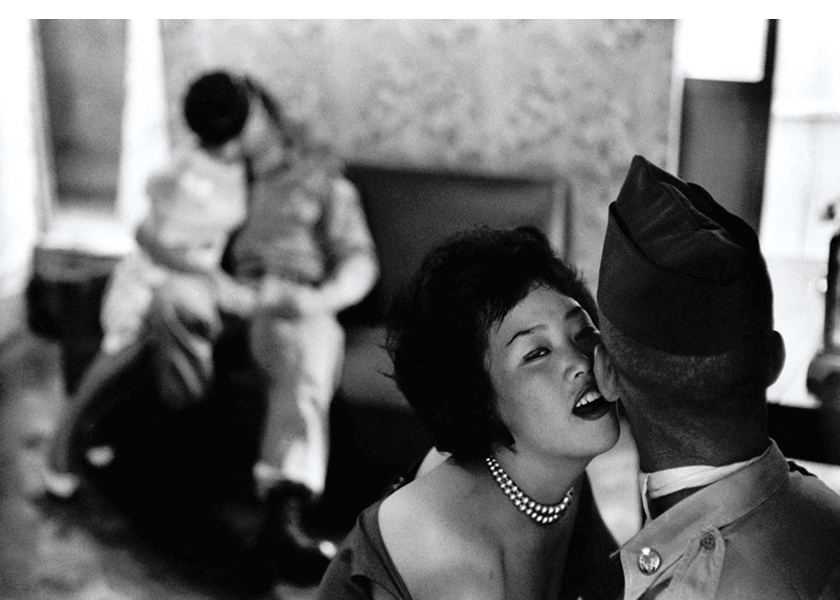

American occupiers were at odds with the Koreans due to social, cultural, and language barriers. The Americans reminded the Koreans that they were from a powerful nation and they were the self-proclaimed saviors of a powerless state. By Koreans, Americans were viewed as self-serving, bearing a superior attitude toward the poverty-stricken natives.

Under President Harry Truman, a new war of ideology was seeded. The Nazism and Fascism that were the enemy ideas during World War II were destroyed. Communism and the fear of totalitarianism were on the horizon of geopolitics. Korea would become the testing ground of new world order ideologies and opportunities. No one could have foreseen the dismal failures to come from 1950 to 1953.

One UN Command Camp #1, POW Koje-do, on an island off the coast of Pusan, was established in 1951. That camp would eventually be the largest camp under the Geneva Convention regulations, housing as many as 170,000 POWs.

Top of the priority list for the use of this camp was as a source of military intelligence, to be gathered through prisoner interrogation. The U.S. set up a Psychological Strategy Board (PSB). Japanese, Korean and Chinese translators were present in the interrogation, but the POWs resented them.

U.S. security also had issues with these translators. Of note were the Japanese Americans recruited as translators, which made for an unusual social dynamic. The Japanese faces were those of the enemy nation for both the Americans and the Koreans. All parties, including the translators themselves had war resentments toward the other, since the Japanese American translators had been incarcerated in their own country during the war because of their race. The U.S. military fought the Japanese, and Koreans saw the faces of their former colonizers.

The interrogation rooms overflowed with mistrust and hatred. It was a challenge to establish the level of trust needed for military intelligence. Outside the camp, the U.S. military trained South Korean men to be guards around the burgeoning camps.

The POW camps soon filled with civilians as well as suspected spies, leftists, Communists, and dissenters. The PSB decided to test psychological warfare among the huge population of prisoners. The political rationale was to hold totalitarianism at bay. The new Cold War proved useful for contrasting democracy to communism, and converting Koreans to the superior American way.

Also at the frontier of psywars at that time, there were rumors of Russian and Chinese brainwashing programs on U.S. POWs. This new kind of warfare both tantalized and frightened the American military.

The larger POW camps also developed their own internal, social stratification. A facility might house civilians, defectors, pro-Communists, anti-Communists, Chinese and Korean POWs. The prisoners quickly organized, and insults led to physical assaults and shootings. Ruling over such huge populations presented another kind of battlefield.

One of the most embarrassing events to occur in the Koje Island POW camp was the hostage taking of the camp military commander, U.S. Army Brigadeer General Francis Dodd on May 7, 1952. A Korean POW of sizable strength caught Dodd off guard and literally carried the general into one of the POW compounds. The prisoners unfurled a large banner, with a message printed in English and Korean: We have captured Dodd. He will not be harmed if PW problems are resolved. If you shoot, his life will be in danger.

The incident took over the U.S. media, which played it up a a kidnapping by the Korean Communists. On May 10, U.S. tanks rolled in to the prison island and parked on the road outside Camp 76 where Dodd was held. The prisoner complaints were largely about issues of humane treatment. Dodd was released unharmed on May 10, 1952 after he and another officer, General Colson signed statements drafted by the POWs. Both were relieved of their Korean commands, demoted, and sent home. Their signatures on an enemy statement were viewed as an act of transgression.

The POWs had seized the moment to redefine their status. There were larger issues of recognition and sovereignty by the POWs. The U.S. military initiated a long investigation, identified the prisoners, but could do little in terms of retaliation without opening other POW issues. The war was still active, and POW populations were growing. The U.S. military draft of The Handling of Prisoners of War During the Korean War was published to impose some policies and consistency on the handling of prisoners. A new commander, Brigadeer General Haydon Boatner, arrived.

The author also describes some dynamics of camps run by UN-Indian forces, and the conflicted repatriation process when POWs were released and a certain number did not want to return to their home states. In other wars, prisoners were tagged and shipped home. The Korean War had the participation of multiple nations, each insisting a say and vote in the POW process. India persisted in the enforcement of POW rights, offering prisoners the option of returning home or choosing a new country.

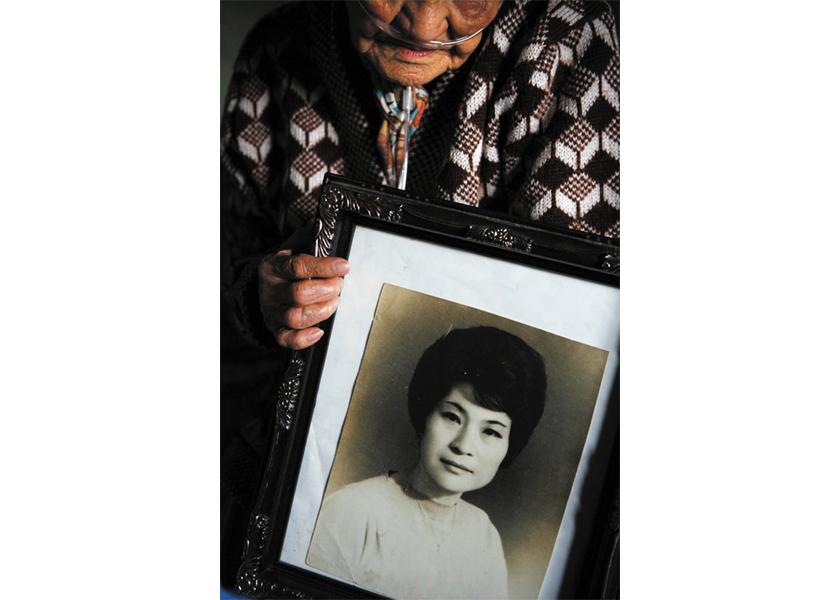

After the July 1953 cease-fire, the U.S.-UN POW camps sent prisoners to the North-South border village of Panmunjom for processing. Ideally, arrangements for liberation of a POW addressed positive self-determination, citizenship, and post-war life. For the Korean POWs, the cruel reminders of war remained. For America and the new South Korea, the repatriation of prisoners was pragmatic; it was better to expel them before issues of prison life and torture in the interrogation room, and other military or political embarrassments came to light. It was time to close the door on many uneasy incidents of war, not just the issue of POWs.

It is fortunate for readers that scholar Monica Kim has researched and brought to light a neglected chapter in Korean-American war history. This is not a revisionist war history, rather, it is a disclosure of a seldom-researched part of a complex period of Korean history. This is a big, detailed, and engrossing study on Korean War history, with lucid accounts of a neglected part of the war that still lingers.

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.