The 2018 Hapa Tour takes Korean adoptees to the neighborhoods of their birth | By Martha Vickery (Fall 2018 issue)

The Mosaic Hapa Tour, a homeland tour tailored for the needs of half-Korean (hapa) adoptees, is a study in contrasts. The mixed-race adoptees, who were once sent from the country in haste to spare them from the country’s poverty and oppression of half-Korean people in post-war Korea, are welcomed back like honored guests, many to the same cities from which they were sent away.

The tour participants, most of whom are older adults raised with little knowledge of their past and no one to talk to about it, are deluged during the tour with information from social scientists and researchers, as well as through conversations with regular neighborhood people who also grew up as kids in the camptowns. A few people even have reunions with birth family during the tour; each individual at least has a chance to go to a significant place, even if it is only a place on the pavement of a city street where they were found abandoned as children.

The tour members also have the rare experience, for many a first experience, of being in a group of other hapa adoptees. After living in an in-between state, unique in appearance and background in school, at work, and even in groups of other Korean adoptees, to be traveling in a group with a shared racial background and history is powerful.

For this third tour, there was a group of 24, seven of whom were Minnesotans. The group bonded like brothers and sisters, and leaned on each other through experiences that were both evocative and emotional. All looked very different from one another, but in an indescribable way, looked and acted like they belong together.

When Me and Korea arranged the first Hapa Tour in 2014, it was the first of its kind. Before that, no tour for mixed-race Korean adoptees had been offered. Although homeland tours are offered by many organizations and some adoption agencies, they tend to concentrate on younger, full-Korean adoptees, including children, high school and college-age students.

This tour, geared for older adults, some of whom were in the first wave of Korean adoptees, concentrates on places of interest for hapa adoptees. They look at the neighborhoods of former camptowns where their Korean mothers may have lived, and tour the grounds of (now closed) U.S. Army bases where their fathers may have been stationed. It also offers some standard sight-seeing, lots of Korean food, and fun cultural activities for the group.

This August marked the third hapa tour. The relationship of Me and Korea with city governments and other sponsors has grown since then. Sponsors of the tour included the camptown cities of Bupyeong and Paju, a church and several companies. Historical and social science organizations helped with the information and history portion, which included a special lecture/discussion and tour of the Bupyeong History Museum. It also included a one-day conference at Seoul National University, at which researchers, documentary filmmakers and government officials shared their work on topics having to do with camptown history.

Although there are an estimated 40,000 hapa Koreans adopted internationally, of an estimated 200,000 total Koreans adopted to all countries, hapa adoptees have been a quiet group until recently. Certain important events changed that, including the first hapa tour followed by the Koreans and Camptowns conference in 2015, which created its own momentum for hapa adoptees to connect. The new technology of DNA matching is also important, because it has allowed many hapa adoptees to find their American birth fathers through half-siblings and cousins. DNA matching in Korea with women who placed children for adoption is also ongoing.

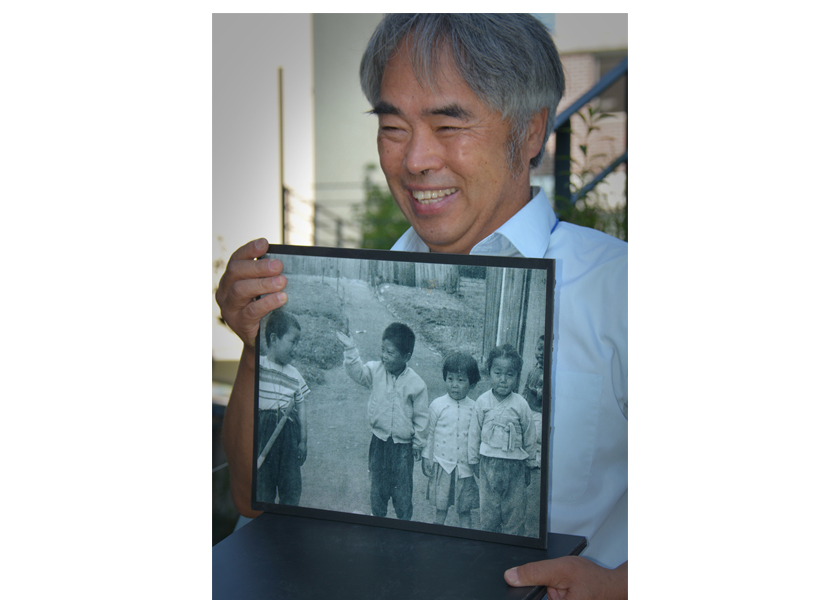

On a sunny morning in Bupyeong, the group visited the 61 Avenue Gallery Café, where they had an art lesson in painting paper lanterns as an ice breaker. After that, there was a short address by Myong-sik Park, a lifelong resident of Bupyeong about changes in the town, and the location of the base and the camptown, known as the Sinchon or “new town” neighborhood. The area was a playground for him and his friends, Park said, and was also a busy area where there was a military hospital, base and weapons manufacturing plant. The base was established at least five years before other South Korean bases were built, he said.

Park said he remembered many friends who were biracial, and said he still misses one friend, he called Dada. “But I think his name was really Daniel, and I think he went to America,” he said.

The day was all about Sinchon, a Bupyeong neighborhood that grew in population during the ‘60s and ‘70s because of the large U.S. military base located there. Now, a fence separates the sidewalk from the former base property. At one place, a divider is plastered with signs demanding action from authorities concerning the contamination still in the soil. There are continuing controversies about what government should pay for the restoration of the land to the city, Park said.

The group got a tour with Park through the deserted pathways of the former base, where no buildings are standing. Concrete slabs, walls and foundations poke through the grass and brush, etching a general picture of the layout.

Later in the day, Jong-A Kim, curator of the nearby Bupyeong History Museum, showed air photos starting in 1947, when there was empty land in Sinchon. She explained that the base area was occupied by a Japanese military installation and arsenal during the Japanese occupation of 1910 through 1945. After the Japanese surrendered and vacated, the U.S. military moved in. By 1967, the open space was filled in with buildings, and by 1997, high-rise apartment buildings occupied what was once part of the base.

The U.S. military presence changed what Bupyeong looked like, Kim said. “Everything revolved around providing all kinds of businesses and services for the U.S. military.” For example, there were many English language signs in Sinchon, even in the 1960s, which was not common in other places in South Korea at that time. Bupyeong was where most U.S. military arrived before they were deployed to various bases in South Korea.

U.S. soldiers used to call Sinchon “Candyland,” Kim said, probably because they “could find anything they wanted at a very cheap price.” There were entertainment clubs inside and outside the base, she said, with separate clubs for officers and regular soldiers. In the ‘60s, the clubs were also segregated for blacks and whites. There were also pharmacies, grocery stores, laundries and other retail businesses Sinchon supplied many jobs to locals at that time.

Women in the sex trade in that area had various arrangements. If they were lucky, they entered a “contract marriage” in which a soldier would provide a home and economic stability for an agreed-upon period. Others worked as more traditional prostitutes, servicing many men every day, she said. “Some also sang and danced at parties, but were exposed to drunken soldiers, harsh words, and violence,” she said.

The dream of women in Sinchon “was to marry an American soldier and escape by moving to America,” Kim said. Women were often in debt to landlords for room, board and supplies like dresses and makeup. The term “comfort woman” a term for military sex slaves during World War II, is sometimes used for sex workers during this time, because they were also controlled by their employers. If they tried to escape, they would be caught and sent back.

Of the total economy of Korea during the immediate post-war era, 10 percent of revenues came from women in these jobs, Kim added. The government back then used the term “industrial warriors,” referring to the contribution they made to the nation’s economy, but on the other hand, for a lot of cultural and social reasons, women in the sex trade were generally reviled by the general population, she said.

At one point, Kim said, the U.S. government asked the South Korean government institute a system to control sexually-transmitted diseases (STDs). The Korean government complied, not wishing to negatively affect the camptown businesses. Women who tested positive for STDs were treated with drugs that often had harsh side effects. If they tested negative, they had to wear a card on the outside of their clothing showing that they were disease-free, a humiliating policy for the women. “But the American soldiers had no controls on them for STDs, such as not allowing them to go to the Sinchon clubs,” Kim pointed out.

Two lifelong residents of Sinchon, Young-sik Kim and Sang-bae Lee, discussed their lives as kids in the camptown, and growing up through one of Korea’s most poverty-stricken times. Young-sik Kim said his mother made her living doing the laundry of soldiers and women in the camptown. She used lye, because detergent was too expensive, and had to carry heavy loads of laundry to the creek, even in the winter, he said.

“I had a big family of eight kids, and our mother had go out to work and then come back and take care of us,” Kim said. He said his memories were of just hanging around, and sometimes going to look for things to eat, since he and his siblings were always hungry. Comically, he described that he used to dig up things to eat he did not know the name of. As an adult, he learned they were called Jerusalem artichokes, and “they are supposed to be all-natural stuff,” he said.

The two men answered some questions about camptown life, including one from a tour participant who asked why a woman would feel she would be forced into prostitution. “We were so poor and hungry,” Kim said. “I don’t even know how to describe it.” He said that people would go and get scrap food from the U.S. base, used for pig feed, go through it, and make soup out of the better parts. Kim was one of a few former camptown residents who talked about “oink-oink porridge,” a very common practice for getting something to eat in those days.

“They would strain it and find some meat pieces —- beef, turkey or chicken,” he said. “and while we were eating, we would find toothpicks, sometimes tissues, and cigarette butts. You wouldn’t believe it. That’s how we lived.”

One tour participant said she was told her brother was born in Bupyeong in 1963, and placed for adoption three years later, and that “he was being passed off to other women and was being abused.” She asked “where were all these children going who were being born?”

Lee said that when he left for the military in the mid-‘60s, there were still a lot of mixed race kids in Sinchon, but when he returned a couple years later, most were gone. It seemed like a neighborhood of biracial kids had been shipped off to America. “Back then, it seemed like every other house had a woman with kids from an American soldier. That was very, very common,” he said.

Curator Jong A. Kim added that back then, if a single woman was trying to raise her child, that meant she had some hope of getting married to a soldier and moving to the U.S. “A lot of soldiers lost courage about having a new family and moving to America. A lot of soldiers had families at home already,” Kim said. Some soldiers got discouraged once they got back home, or deceived the mothers of their children into thinking they would return. The mothers “would place their children for adoption when they knew there was no hope left,” she said.

A month after the tour ended, Elise Nelson, a tour member from Hopkins, reflected on her first trip back to Korea. She has learned a fuller, grimmer picture of life in Korea in the era when she was born. “The way I have explained it to people, all these years, was a really simple adoption story,” she said, “something like ‘my mom was an entertainer for foreign soldiers, she got pregnant by one of them, they lived together for a year, and he left her when she was eight months’ pregnant,’ and that’s pretty much it.”

As the tour progressed, things she learned “completely changed my story,” she said. “Now, it is not a simple story. It is a story filled with heartbreak and hardships, and atrocities, and government involvement, and the poverty, humiliation and violence towards people. It’s unbelievable to me,” she said.

Her adoption papers listed her mother as 32, and her father as 34. At a difficult meeting with Korean Social Services, the agency that handled her adoption, during which the staff person would not allow her to directly see the file, the woman mentioned that her American father was listed as age 22. With that information, Nelson said she doubts the whole premise of her parents having a long-term relationship and living together.

Vance Allen, of Arlington, Virginia, said the tour’s history component was valuable, to him as a member of the “first wave” of Korean adoptees —- the 243rd baby to leave the Holt agency to the U.S. “It reinforced to me how lucky I was to have been adopted, and to have escaped that place. It also made me sad, to think that my mother would have been a comfort woman.” Some of the adoptees resented that the researchers and professionals assumed all the mothers were prostitutes, he said. “Most of us don’t even know our mothers, and though I don’t want to live in a fantasy, it’s a lot of information for one to take in, and try to relate it to your own life —- how you might have been conceived, or what your life would have been like if you had stayed in Korea.” Just being biracial during ‘50s or ‘60s in Korea would have been impossible in itself, he said.

Allen said he almost cancelled his trip, out of anxiety. “I was thinking, oh, I will go over there and get spit on or whatever —- I built all this crap up in my mind.” But, he said, everyone was treated well there. There was one incident where their large group of about 20 Korean/white and Korean/black hapas was turned away from a Bupyeong bar, because the owner declared “no foreigners,” he said. They were welcomed —- and so was their money —- at a nearby bar.

“I thought this would be my first and last visit to Korea, and now I want to go back,” he said. Having the group there, and learning the history through experts and residents of the area made it a complete experience. “This trip did something for me,” he said. “I’m not exactly sure what it did yet, but it was something really positive,” he said.

Elise Nelson added, “I think [the history] piece of it made me really own this trip, like it was a life-changing trip for me. …Even though I had the schedule of what we would do before [the trip began], it didn’t even dawn on me what kind of an impact it would have. I didn’t know enough about the facts, I realize now.” She is grateful to have more knowledge now, she said, even though “it was completely overwhelming.”

Sinchon expert Myong-sik Park, who worked to make Sinchon thrive and who now works to remember its history, said he feels a kinship with biracial Koean adoptees. “We are the survivors,” he said. “We are the people who ate oink-oink soup.”

Life on $129 per year

Koreans and Camptowns Conference strives to put camptowns and their former residents in the historical record | By Martha Vickery (Fall 2018 issue)

SooJin Park, director of the Asia Center at Seoul National University (SNU), addressing the assembly of the Koreans and Camptowns conference, held September 10 at the Asia Center building on the SNU campus in Seoul, joked that he was asked to prepare a short address for a few hundred “students,” but then found that the students were all grown up.

The hapa, or half-Korean adoptees who attended the conference are mostly older adults; many left the country at a variety of ages — babies to older children — in the post-war years of the 1960s and the early ‘70s, for homes in the U.S., Canada and Europe. Other attendees included a few actual students, as well as researchers, academics and adoption professionals from South Korea and the U.S.

Park approached his address in the form of a pop quiz. “How old do you think I am?” he asked. The right answer was 52.

Using his birth year, 1966, as a conservative benchmark, a good 13 years after the Korean War ended, Park asked the audience “What do you think the average personal income was in South Korea in 1966 in U.S. dollars?” He gave a hint by adding that the U.S. (per capita) personal income was $4,000 at that time. Audience members guessed $2,000 or $1,000 or $500. The actual answer, he said, is $129. At the same time, the personal income in Ghana was $160. In North Korea, it was $200.

In 2017, South Korean average income rose to $32,000, U.S. is at about $33,000 and North Korean average income is around $1,400. During that period, Ghana’s rose to about $1,669.

South Korea’s drive to develop its technology, the U.S. influence on South Korea, and even democracy may have caused South Korea’s economy to shoot up in the years since 1966, to the 11th largest economy globally, he ventured after taking the audience through another guessing game.

“But I don’t know the answer,” he confessed, to audience laughter, adding that the Asia Center was founded nine years ago to study that question, “to research the dynamics behind South Korea’s government and to try to export ideas on development to other countries.”

The pop quiz and the revelation of the drastic change in South Korean’s economic circumstances, set the context for a day of short lectures, summaries of research, and even some documentary film footage on what happened when the U.S. soldiers, with a lot of money in their pockets, moved in with their bases next to impoverished South Koreans in the years following the war.

Mixed-race people, now middle aged, are one of the many products of this intersection, and the central topic of the conference. Peripherally, speakers talked about negative and positive results of the camptown era, which takes in everything from the Cold War and extreme anti-communism, territorial and power disputes, and sexual and racial politics to the origins of K-pop in camptowns and the development of Spam cuisine in Korea.

Camptown history buffs

Speakers were from a variety of backgrounds, including Jong-Hwan Choi, mayor of Paju, a city located on the Demilitarized Zone border. Choi is leading his city through a transition which includes the incorporation of a large tract of former U.S. base land, a small piece of which was developed as a park, and dedicated to hapa adoptees and their birthmothers. The opening of the new park, Omma Poom, took place the day after the conference.

Two filmmakers also contributed to the conference. Kyungtae Park has directed and produced several documentary films about camptown women and mixed-race Koreans in the camptowns, including Me and the Owl (2003), There Is (2005) and Tour of Duty (2012). He showed some raw footage he received from a U.S. veteran, showing people’s interactions, army life, and business in the camptowns during the ‘60s.

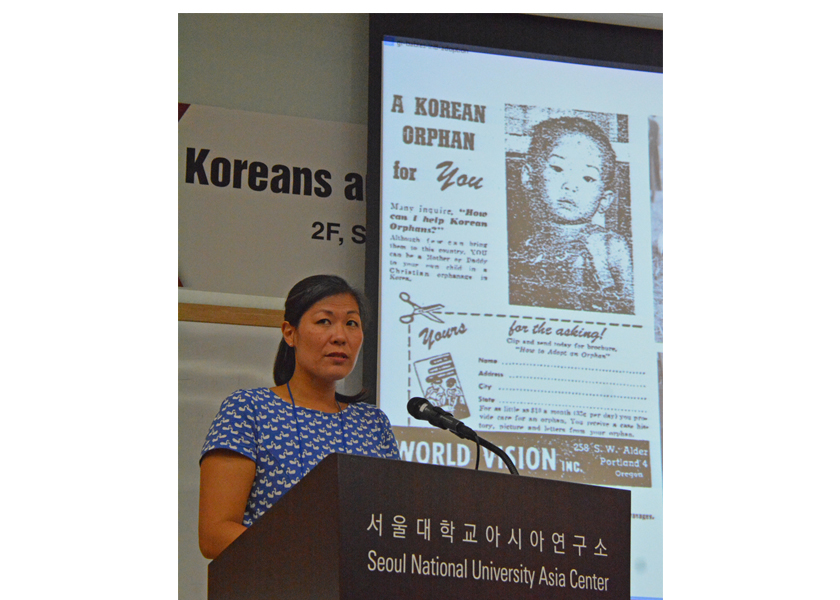

Deann Borshay Liem, a U.S. filmmaker, showed excerpts of her then soon-to-be-released documentary Geographies of Kinship, on the history of Korean adoption dating back to the immediate post-war era. She has produced two documentaries on the Korean adoptee experience including First Person Plural and In the Matter of Cha Jung Hee.

There was a session by researchers interested in the history of the camptowns, and the future disposition of U.S. base land, some of which has been handed over to the government of South Korea as the U.S. military reduces its footprint in South Korea.

Seung-Ook Lee looked into the geopolitical incentives, and the belief systems that motivated the U.S. to deploy troops globally — that number is now at 190,000 worldwide, and whether that mindset is changing. Yilsoon Paek, of the Center for Asian Cities, discussed urban projects to plan for the future use of land that used to be U.S. bases. Paek said some cities wish to preserve the history of the camptowns in some form rather than wiping out all evidence that they ever existed. “There is a need to change the negative image of the camptowns to preserve the history of the camptowns,” he said.

The slate of speakers included several American academics: Arissa Oh, a professor at Boston College, who has researched the roots of international adoption from Korea, Hosu Kim, professor at Staten Island College, New York City, who has researched transnational adoption from a feminist lens, and Sue-Je Lee Gage, who is an associate professor of anthropology at Ithaca College in Ithaca, New York, who has studied the experience of mixed-race Koreans in Korea and in the U.S.

Arissa Oh. Photo by Stephen Wunrow

Arissa Oh. Photo by Stephen WunrowHapa adoptee stories

Gage is a professor at Ithaca College in Ithaca, New York, and has researched, interviewed, and written about mixed Koreans who live in Korea. She introduced a panel of four conference participants who talked about what they could remember about their lives in Korea, and what their plans are for the future.

Gage, a biracial Korean American, said not all biracial Koreans have similar experiences. Some biracial adults and children were able to immigrate to the U.S. through the Amerasian Act (1987), some stayed in South Korea, while others were adopted internationally. Similarly, mothers of biracial adults are often grouped and labelled as former prostitutes. But not all became pregnant because they were prostitutes, not all worked in the clubs established for the U.S. servicemen. “We have shared connections, but there is no archetypical experience for any group,” she said. “It is the history that connects us.”

The four panelists included Maria Giannoble Johnson, from Edina, Minnesota, Chang Lee Nilson from Copenhagen, Denmark, Samuel Townsend from San Diego, California, and Soonhie Sargent of Boise, Idaho.

Unraveling the story

Johnson said she was placed for adoption at age seven in 1970 and lived for a short time in the Holt Orphanage with her brother. The two were adopted to Minnesota, in different families but close enough that they saw each other after their adoption. Her adoptive family included birth siblings of her adoptive parents and one Korean adoptee brother. Her family now includes a husband, married daughters, three grandchildren and one on the way.

When she was placed in the orphanage, it was because she was very ill with both tuberculosis and hepatitis. Her sense of time, and memories of the months after she entered the orphanage are skewed due to the trauma and illness, she guesses. “I know it was fall because I remember the fall colors. I don’t remember winter, but remember spring and still being in a hospital bed.”

She remembers her birth father, a tall man of Asian descent, living with the family from time to time. Another point of confusion, “whether he was from a Hawaiian regiment or other American regiment or was from the UN troops. I was always told he was an American Hawaiian, but then others said he must have been from the UN [allied troops from other countries], so now I am totally confused about that.”

Johnson was on the Hapa Tour for the second time; her curiosity to unravel her past awakened before her first tour, and she is learning her history in bits and pieces. Through DNA matching, Johnson said, she has met her cousin. The two have talked about their grandparents who lived in the rural western region of Choongchungnamdo. Her cousin sent her a photo of her grandparents — her petite grandmother and very tall grandfather are just as she remembered them. “I have vivid memories of my grandpa and grandma taking care of me while my mother was at work,” she said.

Recently, she and her birth brother did a DNA matching test, sponsored by the Korean family search organization 325KAMRA, founded by several hapa adoptees in 2015. The foundation is funded by a grant from Thomas Park Clement, also a hapa adoptee. Through DNA matching, Johnson said, she found another cousin, Coral, who told Johnson she sounded just like her mother, who had died in 2014. Johnson was surprised when she saw a photo of Coral’s mother, that Johnson and her aunt looked like twins. “She was five years younger than I was,” Johnson said. “That was the first time I got chance to see somebody who looked like me. …it suddenly made sense that I belong to this family.” Through Coral, Johnson also found three other first cousins. “If I look at my cousins and my little brother, I can start to see what my parents looked like. I have a family that is growing now through DNA [matching technology],” she said.

Growing up a Korean-African American in Korea

Chang Lee Nielsen was adopted to Denmark 1971, but has been in contact with his Korean family for 16 years and has made many trips back to South Korea since then. Brought up in an area known as Songtan, near Pyeongtaek, where there is still a U.S. base, Nielsen said his mother was promised by the agency that he would be adopted by a family in Minnesota, where he could meet other African American people. Why he ended up in Denmark is just one of the many mysteries in his life. He said he remembers his mother teaching him English phrases and words in preparation for his new life.

“The story my mom told me about her pregnancy and birth is that when she found out she was pregnant with me, she was in a relationship with an African American soldier in Songtan,” he explained. His father “demanded that she get an abortion, because she was in no position to raise me, and she went to my grandmother’s home to think it over. She said she soon found out that my father wanted to break off the relationship with her and that he had started a relationship with a woman who was my mom’s best friend.”

Nielsen lived in Songtan until about age six. “I have a lot of memories, unfortunately, from my life in Songtan as a black Korean. I remember people yelling, screaming and throwing rocks after me. My halmoni protected me, and I had an older cousin, Park Chang soo … he did everything he could to protect me from all the horrible things. I don’t remember any other mixed race person. I think I was the only one in that area.”

As a young adult, Nielsen said, he did not search for his birth family, although the need to do so was on his mind. One day in 2002, he got a letter from his Danish adoption agency telling him his birth mother was looking for him. When he called the agency, they said they could give him her phone number. “I called her and said ‘I think that I am your son —- my name is Chang Lee Nielsen,’ and she started to cry. I think we both cried on the phone for 15 minutes.”

He recalled the rush of emotion at his first reunion with them, especially when his Korean family called him by his old nickname “Cha-lee” (Charlie). His first visit back was 31 years after he left at age six. His mom, uncle, older cousin and a younger cousin born after he left, all greeted him. “The best day ever, to see the family I remembered, came true,” he said. After the Hapa Tour ended, Nielsen stayed for a couple more weeks and was able to celebrate the Korean harvest festival, Chuseok, with his Korean family.

Nielsen said his favorite film is Taeguki, a story that takes place during the Korean War. “I like it especially because it is a story of an older brother who joined up with the army in order to protect his younger brother. That reminds me of my hyung. [older brother]. Think I have watched that movie five times, and every time, I cry,” he said.

Making up for lost time

Samuel Townsend, was born in 1953 in Seoul. Abandoned on the streets, he only knows that someone brought him to a hospital, malnourished and sick. After he got well, he was placed in a Methodist orphanage, where he stayed until he was about three and a half. “They decided to make my birthday March 1 [the day when Korea declared independence during the Japanese occupation] …and they named me Sam after Uncle Sam,” he said. “For my entire life, I have looked in the mirror and wondered what I looked like. And I really still don’t know what I look like.”

During the Hapa Tour, he said, he discovered that there was someone else on the tour who was placed in the same small orphanage where he lived, and that she was there at the same time. “That is one of the first pieces of hard evidence I have of anything that’s real. Until now, everything has just been imaginary. I probably played with her.” The discovery was the first one that gave him a sense of Korean roots.

He came to the U.S. on a plane “with a missionary I called halmoni,” he said. “I spoke quite a bit of Korean at age three and a half, and now I speak about three words,” he joked. After his adoption, he said “I did whatever I could to become as white as possible. I was adopted into a white family and they had adopted two white children, and the town we lived in was completely white. They would tell me that ‘you just need to know that you are really special,’ but I felt that I wanted to not be special, and spent most of my life pretending I was not Korean,” he said. “And now, I am trying to make up for lost time.”

At his office, Townsend said, he encountered a guy delivering water for the dispenser. The two had a rather comical exchange where the delivery man said “‘you look like you are half-Korean,’ and Townsend replied “So do you.” A conversation ensued during which the delivery guy said he found cousins with a DNA matching service. This inspired Townsend — he wants to try a DNA matching service in the near future. “Who knows, there could be gold at the end of the rainbow, and you may as well think positive.”

The last one to go

Soonhie Sargent is the first-born of four children, two younger sisters and a younger brother. One day when she was age nine, she said, her mother sat her down and told her they were all going to be adopted. “I had to trust and accept the fact that she was doing it for us,” she said.

The four siblings were adopted successively, with Sargent last. “I remember going in February with my beautiful blond sister to the airport to say goodbye. Then my next sister, such a small thing and beautiful, in September, and then my three-year-old brother,” she said. “He was like my little boy, all my own, …I remember we were outside playing and the people came and said it was time to take him. I didn’t quite understand what was going on. I didn’t realize they were taking him for good. They grabbed him and put him into the car, and he was screaming out the window Soonhie! Soonhie!” Grandmother, mother, and daughter cried every night after that, she said. The three sisters and brother would not reunite again until 2008.

Sargent said she remembers her whole family, including aunts and uncles, and a cousin Ok-hee, who was her age, and that overall, life was good. A man who she believed was her birth father spent time with her when she was very small, sometimes taking her to the base to shop for canned goods for the family at the PX. He would carry her on his shoulders, and buy her the “most delicious ice cream in the world,” she said, which was vanilla, chocolate and strawberry in the same cone. She asked her birth mother for her birth father’s name, she said, but her mother claimed to not remember it. Sargent is now unsure if her birth father is the same man who took her to the base as a child.

The subtext of why the siblings needed to be adopted was her mother’s wish to be married. She said her mother “wanted a pure life, without children, and she wanted to marry this new man, who I despised,” Sargent said. He was not kind, and he “tortured her every day,” she said. “He reminded her what her life was like when she had us. She tried to get a divorce and he ran away and that cut off the process.”

Sisters Susan Smith and Kimber-Lee Erb were on the tour with Sargent. The three had a joint reunion with their birthmother for the first time (the sisters had had separate reunions with their mother previously). At the same reunion, Soonhie reunited with cousin Ok-hee and their second-oldest aunt. She also met her siblings, two sisters and a brother, that her mother had with her Korean husband. The three had endured their parents’ difficult marriage and emerged “strong and resilient,” Sargent said.

“In terms of the whole family reuniting, I owe that to my two sisters Susan and Kimber-Lee, who found me and called me up one night,” she said. “I was the last one to go, and the last one to be found.”

The Koreans and Camptowns conference was co-sponsored by the Center for Asian Cities, Seoul National University, and Me and Korea, a U.S. non-profit organization serving Korean adoptees and their families (website: meandkorea.org)

A homecoming park

Dedication of Omma Poom in Paju symbolizes Korean society’s recognition of birth mothers and adoptees | By Stephen Wunrow (Fall 2018 issue)

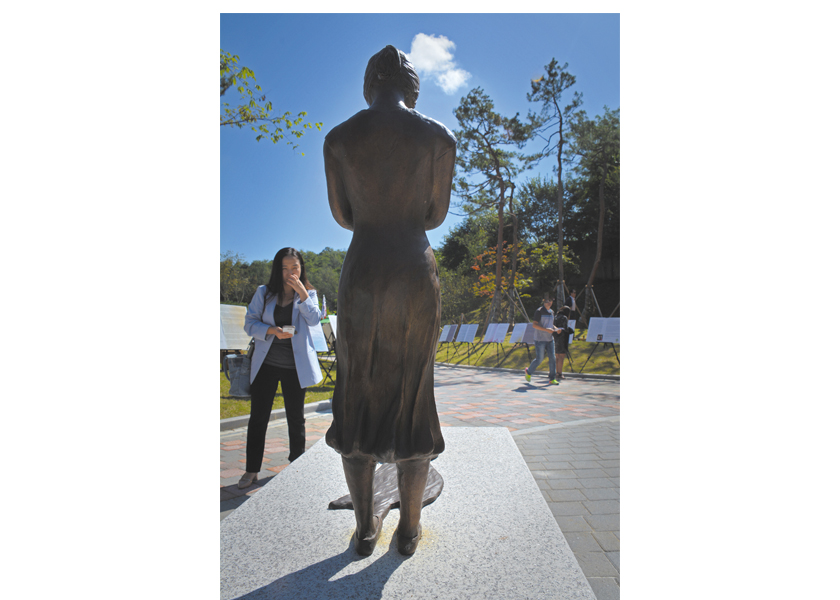

Hundreds converged on a small piece of land carved out of the woods in the city of Paju on September 12 to dedicate a park to the birth mothers of Korea who sent their children for adoption.

The park was a joint idea of the City of Paju with the Me and Korea tour organization, and its director

Minyoung Kim. In late 2014, Kim brought the first group of hapa adoptees to the city of Paju to see the former site of Camp Howze, one of the largest and oldest of the U.S. military bases in Korea in an area bordering the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

At that time, the city was planning for a development on land that was the former Camp Howze, which had been turned over to the city in 2005. The park development cost nearly $1 million, including the land, sculptures, trees and landscaping, according to Paju Mayor Jong-hwan Choi.

The circular memorial, called Omma Poom (Mother’s Arms) is set on a nearly 24,000 square foot clearing in a relatively remote wooded setting deep inside the former Camp Howze. The park is an oval shape, surrounded by trees, with a giant shell-shaped sculpture at its center. The sculptures are all on the theme of motherhood and the mother-child relationship.

The park is dominated by a huge central sculpture, by Kwang Hyun Wang, a series of white concentric circles, suggestive of the sleeves of a traditional Korean outfit (hanbok) and an enclosure in a mother’s arms.

Although many officials offered remarks during the opening, the focus was kept on the Korean adoptees who assembled there. Two offered letters to their unknown birth mothers, supported by several birth mothers of adoptees who stood with them while they read. Members of the 2018 Hapa Tour, which had just ended two days before, sang a Korean song. Hapa adoptee Estelle Cooke Sampson, an M.D. radiologist from Washington, D.C., offered some words of gratitude on what it means to have the recognition from Korean society symbolized by the park.

Wonsook Kim, a Korean American visual artist from Indiana, donated a sculpture entitled Shadow Child, which depicts a standing woman with her arms crossed, and her shadow on the ground, except in the shadow, the arms are holding a baby. Every woman has a concept of motherhood, Kim said in an interview later, and the “shadow in their heart” can reflect grief over abortion, divorce, miscarriage or other incidents. “It resonated with every woman there, I think,” she said.

Kim attended the ceremony with her husband Thomas Park Clement, a hapa Korean adoptee, who has donated a $1 million fund to help adoptees and their families reunite through DNA matching.

The biracial Korean pop star Insooni attended the ceremony, and expressed gratitude to the city for the park and the idea behind it. She promised the Korean adoptees in the audience that she will return to the park from time to time to enjoy it, and pull weeds there.

Omma Poom, which will eventually be part of a larger neighborhood park, will not be open to the public until the entire project is complete, but it will be available by appointment. The city conferred awards to people whose contributions were key to the creation of the park, including Minyoung Kim.

On the dedication day, the park was surrounded at one end by a display donated by Korean adoptees. Each card had a photo of the donor with a message either about the park, or a message to the donor’s birth mother. The exhibit of 648 messages from 17 countries with the adoptee’s name, Korean name, and place of residence “proves that adoptees are a part of Korea’s history, and delivers adoptees’ voices to Korean society,” according to an emailed letter from Me and Korea about the project. Adoptees and their friends and families took photos of themselves with their own photo in the display. The display was paid for by the alumni of the 2018 Me and Korea Hapa Tour, many of whom attended the ceremony.

Korean Quarterly is dedicated to producing quality non-profit independent journalism rooted in the Korean American community. Please support us by subscribing, donating, or making a purchase through our store.