Familiar people and activities and the orderly nature of fall | By Martha Vickery (Fall 2022)

In addition to visual cues, like geese practice-flying in a chevron shape in the sky or noticing less

pavement on a favorite walking trail as it gets covered with leaves, there are some energy cues that

signify fall is coming. I sense a certain sense of order about fall, some urges to get mentally organized for

the work ahead. Even for those of us who are no longer affected by school schedules, the instinct to get with it happens anyway as vacations come to a close, and we set our minds to being back at work again.

I also found myself tentatively thinking that perhaps, after two-and-a-half years of pandemic ups and

downs, things are getting back to normal. Or at least, in a state of new normal. Certain activities, like

outdoor festivals in late summer and early fall gave me a sense of old times.

One of the days I felt most normal was the day of the Kimchi Festival, presented by Adoptee Hub, a service and educational group by and for adult Korean adoptees, devoted to social services and cultural enrichment specifically tailored to them. The Kimchi Festival, although designed to provide fun access to Korean culture for Korean adoptees through food, was also of interest to a wide audience.

There was a sense of newness because there has never been a Kimchi Festival in Minnesota before. This was the first one, although Adoptee Hub wants it to be an annual event. It was fun to see the Kimchi Contest judges, volunteers from the Korean American Women’s Association, sit down before a bemused audience to give a little critique of the kimchi samples entered into the contest. It may have been a first-time experience for all of us to hear the results of a kimchi contest. Some were “a little salty,” or “a little fishy,” and a couple of the samples, including one made with asparagus, were pronounced to be “innovative.”

There was also a sense of newness because the Twin Cities Korean American community was showing up to its own large-scale in-person event for the first time in a few years. There were vendors, performers, churches, and community groups. It felt both new and old, and both strange and familiar at the same time.

For me, it was super-fun because I had to stop about every two feet as I walked along, to talk to

someone I knew and had not seen since before the pandemic. It was so satisfying to see so many of the

same people again; to know they were the same and see that they were OK.

The food was good too. I was having one of those moments of joy, resting at an outside table after

getting a couple kimchi samples, when a Korean American guy I did not know sat down next to me and we exchanged a few bits of small talk. One of the things he said was “Isn’t it great to just see the people?” I knew what he meant – it was not only great to see any people having fun at an outdoor event

together, it was also special for me and my Korean family members and friends to see so many Korean

faces at the same event. I felt somehow relieved. Intellectually, I knew the folks were still there. But, yes, it was great to just see them.

Another event in of the fall involves government getting back into gear. I spent some time delving into

the progress of the Adoptee Citizenship Act (ACA) which would confer automatic citizenship on all

international adoptees, irrespective of their age or date of adoption. It would also bring home all

adoptees who have been deported to their country of origin. In 2022, the ACA made more progress than it has ever made in its seven-year history. It was passed in the House of Representatives in February,

then went to the Senate and was stripped from a bigger bill.

To bolster support for the bill, the lobbying group Adoptees for Justice (A4J) sought and received

support at the state level, including a resolution from the conservative state of Utah to unanimously

support the ACA and call for its U.S. Senators to get behind it. It still could get through in the last months

of the 2022 session of Congress. A4J is urging all supporters to tell their Senators to step up and support

it.

Kudos to Sara Jones, a community organizer and Korean adoptee along with all her allies in the Utah

business and government community for all the work needed to get their resolution through the state

legislation. Bi-partisan cooperation can happen!

Also among the fall 2020 stories are reviews of two recent live theater productions that put a new spin

on famous plays. One at Park Square Theater, was The Humans, a Tony-award-winning play that has

seen many productions in many theaters. This one was staged and casted by dramaturg Katie Bradley, a

Korean adoptee, to show this family drama as a family with two Asian daughters. Although nothing new

is added to the play, the substitution of two Asian daughters and one Black boyfriend, instead of a

white family whose members racially match, sends a different kind of message to the audience about

the nature of the drama.

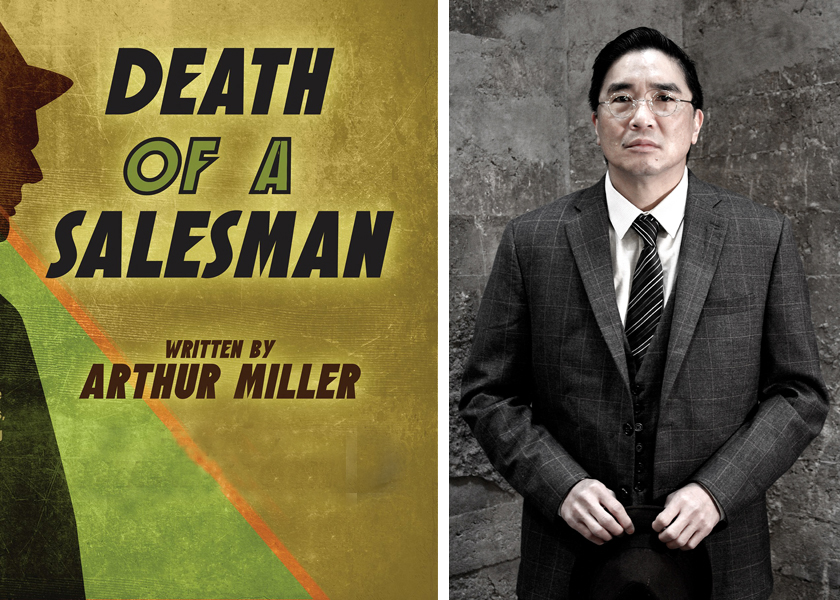

Similarly, Theater Mu’s recent staged reading of the classic Arthur Miller play Death of a Salesman,

directed by local actor/playwright Eric Sharp ( a Korean adoptee) in collaboration with Seth Patterson

and Theater 45, flipped the script on this well-known story of the failed American dream with an all-

Asian cast. Having live theater back is another great joy for Twin Citians as we step into a seemingly fragile new-normal environment.

As we enter the last quarter of 2022, we have to reflect on what a big year it has been for KQ and for all

who support us, as we transitioned from paper and online editions to 100 percent online with a new

digital archive still on the way. Before the end of the tax year, please consider a donation to help KQ

continue to bring this independent, volunteer-driven journal to you into the future. Thanks readers!