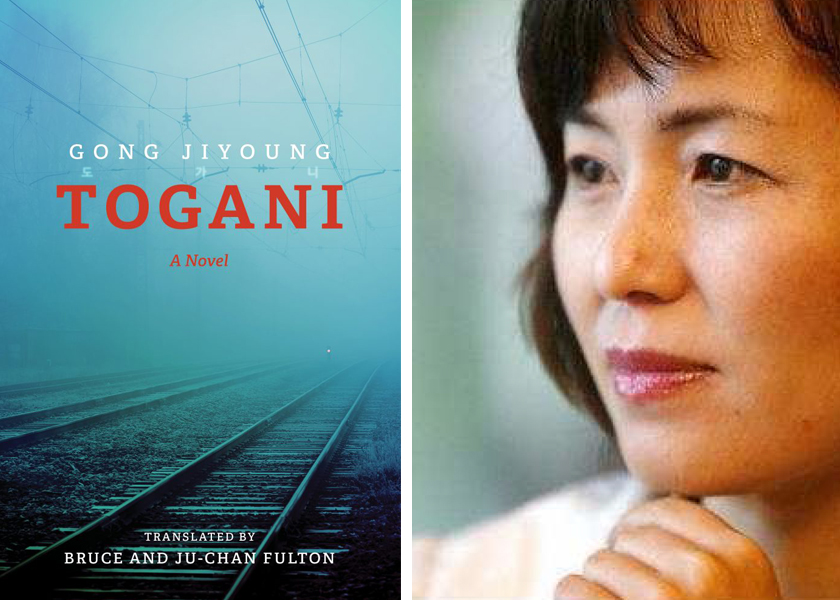

Togani By Ji-Young Gong

(Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton, trans., University of Hawaii Press, Manoa (HI), 2023, ISBN #978-0-8248-9487-0)

Review by Bill Drucker (Fall 2024)

Togani (aka, The Crucible) is a thinly-veiled, novelized account of an actual event, describing how children were abused for years at a school for deaf- and hearing-impaired students. The incidents happened in Gwangju in the early 2000s. This is clearly a novel of criticism about social inequities and injustice.

The story starts when Inho Kang, a special education teacher, takes a job in the remote city of Mujin, a fictional substitute for Gwangju. He leaves his wife and daughter behind in Seoul; the story explains he is taking the job as an escape from a failed business venture, and out of financial necessity. The small-town mindset, the wariness he feels from the locals of big city people, and the frequent fog all create a disturbingly distrustful mood at the beginning of the story.

Driving on a country road, Kang nearly runs into a child. He quickly stops to assist, but the child is swallowed up by the fog, and he cannot find anyone. He reports the incident to the local policeman, Officer Chang. The officer is agreeable and says he will look into it. He promises to call a nearby school to see if the child may have been one of its students.

Soon, Kang gets a visit from a familiar face. It is Yujin So, a woman who at one time was Kang’s classmate. The two have not seen one another for 10 years, and both have moved around to coincidentally end up in the same town. So brings a grocery bag with a gift of detergent, a common housewarming gift, with her, perhaps her way of cutting the tension. After putting down the bags, So suggests they eat out.

Over grilled pork belly, So hands Kang her business card showing that she is the director of the Mujin Human Rights Advocacy Center. The position may have had more influence 10 years ago, when Mujin was known after the (Gwangju) uprisings as a city that was the cradle of Korean democracy. In the present day of the story, it is just another remote city in South Korea. To Kang, So still seems youthful, but with a new edginess, sarcasm, and inner toughness.

At the school where Kang has been newly hired, the Home of Benevolence, he is not openly greeted. The staff seems wary. The principal, Kangsok Yi and his administrator Kangbok Yi, are twins, and the sons of the school’s founder.

In the principal’s office, Kang sees police officer Chang, acting quite chummy. He feels that this is not a good sign. In private, he learns that he is expected to pay a cash bribe to the school for getting hired quickly because of a connection between his wife and a Yi family member. Kang is conflicted, but he needs the job and has made complicated arrangements to be there, so he reluctantly pays.

As the days and weeks go by, Kang keeps reporting to the principal, and talking with the other staffers on what he perceives as evidence of abuse of the children. The children never smile, all wear the same sullen look. He hears screams in the night. Kang is coolly received by staff at first, and after he speaks out, staffers respond with an edge of hostility. One employee bluntly tells Kang to shut up if he wants to keep his job. Kang hears that one child died recently. In addition to rumors and pieces of stories he hears, the lack of sympathy by the school staff toward students and the apparent complicity of the police disturb him.

The quest for justice becomes an uncharted battlefield for Kang, and he goes to So for help. Her attitude is the opposite: she has been waiting for such an opportunity to find out what is really going on at the school. On a fine autumn day, perhaps suggesting clarity of mind and purpose, child advocate So informs her staff they must prepare for a full investigation.

The elements of light and dark are used effectively throughout the novel. Fog is a metaphor for concealment, and obscurity. It is the gray zone between reality and unreality, certainty and uncertainty, justice and injustice. The fog brings foreboding and confusion. It hides the truth. It can bring death.

The investigation leads to a trial, and the novel takes on the characteristics of a crime procedural, with some cultural and psychological variations. The trial begins on a clear day. Merciless tactics are deployed by the defense to discredit witnesses, praise the guilty, and verbally assault the children, and a dark murkiness fills the courtroom.

The days in court prove frustrating. The prosecution fights for a deaf interpreter. The defense takes the line that the prosecution is simply maligning good citizens including the (twin) school principal and administrator, which they describe as pillars of the community. The children who courageously come forward to be questioned in court are ruthlessly targeted. Outside the court, a woman comes up behind So and makes foul remarks to her. So is shook up, but not enough to walk away. The local judge plays it carefully with the press in the room.

The family of one child is approached with a bribe. Kang and So race to get there to catch the bribers, but it was unnecessary. An old woman, speaking for the family, tell them she told the bribers that there isn’t enough money in the world to keep them silent, and sent them packing. Officer Chang suggests to Kang, especially after he was roughed up, that he should also just leave, asking him “what’s in it for you?”

The verdict does not go well for the defense. The culprits are given only a light punishment. Kang feels he is not the warrior he thought he was. His demanding wife and child are still waiting in Seoul, and Kang has no strength left. He admires So, who is a true warrior and a fearless crusader.

So is not done after the verdict. Along with the parents and other supporters of the students, So heads toward the City Hall to demonstrate against the injustice of the light sentence levied against the perpetrators of the many serious crimes against children. It is the 28th anniversary of the Mujin Uprising and the Prime Minister is giving a speech. Police officer Chang, understanding the situation and even empathetic toward the marching crowd, still orders the water cannons turned on. He instructs the police to keep the people from heading toward City Hall. (the publication of Togani in 2009 was 28 years after the Gwangju Massacre.)

Emboldened, the deaf children dish out their own small bit of retribution, gathering at the school to protest that the key offenders have returned to work. The kitchen staff report that cartons of eggs have disappeared. As the principal and staff get back to business, the children storm the office and pelt them with eggs. Police are in no rush to go after the children, and the hysterics of the staff are ignored. The press and investigators are still in town looking for a story.

Author Ji-young Gong had clear intentions in this grim novel of corruption and abuse in a small town. The title Togani refers to Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible. Both stories depict the scenario of a trial that takes place in a small town, with small-minded people. Events lead to hysteria, denial, and attempts to silence the truth. There are lengthy courtroom chapters in Togani describing how the people in Mujin suppressed information of the crime, and denied it once the truth was out. People caught in the crosshairs are fired, threatened, and attacked.

In the 2011 film version, actor Gong-Yoo took the lead role of idealistic teacher (Kang in the novel), who uncovers the child abuse. In the film, entitled The Silenced, the school denies everything, the administrators pretend to befriend the teacher, then get him removed. He is slapped by one of the school adminstrators’ wives.

The sensitive and controversial film received good reviews. A special piece of legislation, nicknamed the “Togani bill,” was enacted to better protect children from would-be abusers in institutions. The real teacher who uncovered the child abuse, and championed the students’ rights was fired and faded from the public eye. The novel reflects the fact that the Gwangju Inhwa school’s administrators received no jail time. The courts dismissed the case for lack of evidence in 2011. The victims’ rights to file for compensation had expired (2010). The school principal died of cancer in 2011. After a series of investigations and public outcries, the Gwangju Inhwa school was closed in 2011.

The author Ji-Young Gong, born in Seoul (1963), is popular in Korea and diaspora Korean communities abroad. She graduated from Yonsei University with a degree in English literature. Gong has published works of poetry, short stories, novels and essays, and has focused her writing on issues of injustice, gender and inequality. Gong received good reviews for Togani, however, she was also investigated by the state’s ruling conservatives for “political activities.”

Translators Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton are arguably as famous as the Korean authors with whom they collaborate. In bringing Korean literature to English audiences over many decades, the Fultons have established themselves as accomplished collaborators who have helped to open up great Korean literature to English speaking readers.