A new peace movement for a new generation | By Nuri Yi and Jeremiah Kim (Summer 2023)

To be a young Korean in the spring of 2018 was to open your eyes and see the world cast in a new light, clear and fresh as morning. That April, North Korean leader Jong Un Kim and South Korean President Jae-in Moon met at the Joint Security Area within the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) for the third inter-Korean summit since the Korean War (special coverage of the 2018 summit appeared in the Vol. 21, Summer 2018 issue of Korean Quarterly, available in the KQ digital archive which is coming soon). It was the first face-to-face meeting of the two Korean leaders in 11 years.

During the meeting, Kim joked that he had brought some of North Korea’s famous Pyongyang-style naengmyun (cold buckwheat noodles) to share with Moon. In that moment, something we took for granted was suddenly imbued with greater meaning: A simple bowl of noodles became the symbol of a people’s hope and yearning to be together again.

The meeting set in motion an unprecedented year of summits and talks among leaders from the North, the South, and the U.S. Throughout the 2018-2019 peace process, millions of us in the peninsula and across the diaspora felt ourselves being pulled toward new horizons. For the first time, we saw our lives as part of a journey to discover a path to peace and reunification.

Perhaps the most striking image from the 2018-19 period was of the June 2019 meeting of then-President Donald Trump with Kim when the two shook hands and stepped over the DMZ into North Korean territory. The sight triggered cognitive dissonance — wasn’t this the same man who had threatened North Korea with “fire and fury” only two years earlier? But there it was: A sitting U.S president, for the first time ever, visiting North Korea and meeting with its leaders. Watching this unfold, we tried to make sense of the disparity between the mainstream portrayals of Trump as a political joke, versus the sober reality of an American leader breaking with nearly 70 years of U.S. policy in the long history of the Korean War.

The 2018-19 talks ultimately failed to produce a peace treaty. Nevertheless, after 2019, something important had changed. For young people who have only ever known the peninsula in its division for more than two generations, it marked an opening of consciousness.

The Kim-Trump-Moon summits were pivotal in that regard. We expected the meeting between Kim and Moon to be jarring — a leader we had been taught to fear and hate coming face-to-face with one of our own leaders from the South. Perhaps it would be tense and distant from the years of mistrust. But instead, both leaders warmly greeted one another, and smiled in a manner that was at once familiar and incredibly normal. When added to this picture, Trump did not appear to be a disruptive outlier but as a part of the trio. Seeing this meeting did something to us. It made us yearn for the day that we might be able to reunite in the warmth of shared brotherhood. It made us believe that peace was a genuine, if uncharted, possibility.

This dawning awareness forced us to ask new and challenging questions. What were the real obstacles to peace, and what forces needed to come together to overcome these obstacles? Was there something missing in our understanding of the Trump phenomenon? What explained the constant barrage of ideological attacks on North Korea, even during peace talks? Gradually, we began to realize the enormity of the peace question and its significance to the Korean people — but not just to Koreans.

July 27, 2023 marked the 70th anniversary of the armistice agreement that placed the Korean War into a state of ceasefire without formally ending the war. We are now, incredibly and painfully, living through the 73rd year of the Korean War. This ongoing war is so old that it is beginning to pass out of living memory, for people on both sides of a still-divided land.

Amid the recent celebrations of Liberation Day from Japanese occupation, we find ourselves today with the Yoon administration in South Korea and the Biden administration in the U.S. pushing for a “mini-NATO” in East Asia alongside Japan. Coupled with the reinstatement of massive U.S.-South Korea war exercises under Biden, tensions on the peninsula have worsened to an unnerving fever pitch. The 2018-2019 peace process, though left incomplete, remains as the most recent high point in North-South-U.S. relations.

Since those years, young Korean Americans have taken different paths. Some have entered the existing Korea peace movement: A loose but well-connected network of nonprofits and progressive-leaning groups that campaign to end the Korean War, lift sanctions on the North, and reunite separate families. Others have made it into the political establishment of Washington, D.C., joining congressional offices, foreign policy think tanks, and lobbying groups that often advocate for regime change and increased sanctions. Many of us are interested in Korean affairs, even among those who are less politically active. Beyond the contemporary impact of the “Korean Wave” in pop culture, there is the looming specter of the partition of Korea which remains with us as a piece of the present, not the past; it has shaped our collective identity and political role in America over the generations.

It is within this context that a recent commemoration of the armistice on July 27-28, termed as a National Mobilization to End the Korean War, brought together activists and supporters of Korean peace in Washington D.C. The event generated some attention in the national media, ranging from supportive op-eds written by participants to unfair attacks painting the organizers as “pro-North Korean” agents simply because they are advocates for peace.

As two attendees of the gathering, we acknowledge and appreciate the sincerity and hard work of the organizers. We feel nevertheless that the mobilization showed many of the limitations of the Korean peace movement in its current manifestation.

Thematically, the event focused its strongest rhetoric on the harm and trauma imposed on generations of Koreans due to the war and its unresolved status. Demographically, most participants were either Korean Americans or white allies. They represented various sponsoring organizations. Politically, the organizers’ primary targets were the Washington elites, and in particular Democratic members of Congress who might be inclined to support a bill calling for renewed diplomacy toward a peace treaty.

This yearly congressional effort is likely destined to stay in limbo, pending a seismic change in the overall political landscape. The Trump movement was the elephant in the room; if Trump was mentioned at all, it was to dismiss him as an egotist whose role in the 2018-2019 peace talks was entirely selfish, erratic, and minimal, if not outright coincidental. Although the present-day dangers of nuclear war were discussed during the commemoration event, the Biden administration and its cast of unabashed neoconservative war-hawks were strangely portrayed as an alternative that was safe and could be reasoned with. Few concrete ideas were offered when it came to the question of how to build broader and more sustained popular support for Korean peace.

This gets to the heart of the issue: Korean Americans, as a part of the greater American society, know that we are impacted by changes that occur in the U.S. However, we have not yet fully recognized the most significant development in the U.S. in recent years — a change that has meaning for ourselves, Korea, and the world. Underneath narratives of racial antagonism or partisan division that dominate the airwaves, the faint outlines of something different can be seen: A new people’s peace movement is emerging in the U.S.

This is not an institutionalized peace movement of nonprofits. It is a peace movement that is only just starting to take shape — it has no central organization, no single ideology or platform. It originates from different corners of American life that have yet to join together as one.

Nevertheless, there is discernible movement in the political life of this country, propelled by a common sentiment: The American people are tired of war. Americans understand intuitively that endless wars have poisoned the well of American life — that the violence and chaos we foment abroad often finds its way back home. Moreover, ordinary people understand that the wars our nation wages are fundamentally un-democratic enterprises, to which they have not consented nor can benefit from — and which have mounting costs, in both money and human lives.

Few exemplify this political reality better than the combined phenomena of Donald Trump, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and Cornel West. In what will be one of the most consequential elections in U.S. history, three major presidential candidates are campaigning explicitly on an anti-war agenda. The nascent anti-war movement finds its expression through a populist coalition that is converging around these figures, transcending traditional party lines. Together, Trump, Kennedy, and West likely represent the anti-war aspiration of more than half of the U.S. population.

In some ways, the outlines of this aspiration can be traced back to that pivotal event in the spring of 2018. While much can be attributed to the efforts of the two Koreas, we must also recognize that the 2018-19 peace process was made possible, in part, because tens of millions of Americans — including the “deplorables” who support Trump — expressed their readiness for a change in this country’s war policy around the world.

Kennedy, an independent candidate and formerly a Democratic challenger to Biden, is likewise gaining some traction precisely because he seeks to dismantle the American war machine, invoking the legacies of his father, his uncle, and Martin Luther King Jr. To this equation, West also brings a trenchant critique of U.S. empire rooted in the Black radical tradition. At a time when the Biden administration is stoking nuclear confrontation with Russia, China, and North Korea, these populist candidates matter, not because they are perfect, but because they capture an unprecedented and growing anti-war sentiment among Americans.

From the 20-year disgrace of Afghanistan to the multi-billion dollar proxy war in Ukraine, some Americans are asking, “How exactly have we been led into disaster after disaster, and now to the brink of nuclear catastrophe, without ever having had a say in the matter?”

Indeed, a growing number of Americans share a simmering anger and distrust toward their country’s corrupt, war-obsessed ruling elite. Across lines of color, class, and creed, we are facing the prospect of a nation in decline, a hegemon collapsing under its own weight. We wonder about our own future. Yet few, if any, look to the existing political establishment to resolve the crisis. The predominant direction of change in America is the widening gap between the elites and the broader group of ordinary people: A crisis in the legitimacy of those who presume to rule over the rest of society.

No serious effort toward peace can afford to reject out of hand the sentiments of these broader swaths of the American people. In fact, they must be embraced and understood as the best way for the U.S. to achieve its unfulfilled promise of peace toward Korea.

This year’s anniversary of the Korean War armistice offers an opportunity to reflect — not simply on the ongoing tragedy of 70 years of ceasefire without peace, but to reassess how a peace movement must be developed today to fulfill the possibilities of the future. To do this, we must understand America today and the places where the impetus and drive for peace exist.

The Korean War era shaped the formation of the U.S. deep state permanent war apparatus, with its indiscriminate bombing campaigns abroad and the targeting of Americans at home under McCarthyism. This entrenched super-state remains fundamentally undemocratic and anti-human, working against the interests of the American people and people of many other nations today. While the American government must be party to a peace agreement ending the Korean War, it is the American people who must transform and reorient the state towards peace — and can only do so with broad support and national unity.

Korean American peace activists cannot afford to pitch themselves solely as an “ethnic” or “minority” pet cause for an affected nationality. If there is to be a chance for the Korean War to finally end, there must be a peace movement that anchors itself deeply within a wide swath of Americans — going beyond the assumptions of primarily white liberal-left groups that often look down upon the rest of the U.S. population.

Neither can a peace movement honestly call itself a peace movement if it is obediently hitched to the wagon of the Democratic Party, which has become associated with the permanent security state and which hosts some of the most fervently pro-war elements of the federal government. A genuine peace movement will seek to connect Korea to Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Ukraine, rejecting the endless war agenda of a depraved system which only the ruling elites see as desirable.

The Korean diaspora indeed has a significant role to play in building such a peace movement. To direct our energies toward a genuine peace coalition can be our contribution to advancing the struggle of the strivings of Koreans in Korea, both North and South. As the younger generation, we can speak on the lingering effects of war — not just as Koreans but as Americans.

The trauma of war has, to some extent, clouded our ability to understand our history. An over-emphasis on trauma conditions us to believe that the brutality of war and the separation of families are incomprehensible forces that have turned all Koreans into a special group of victims. We are prevented from seeing the truth: That our pain is what connects us to a war-torn humanity, at home and abroad; and that the division of our homeland is ultimately a human problem whose resolution will bring new knowledge and energy to the world.

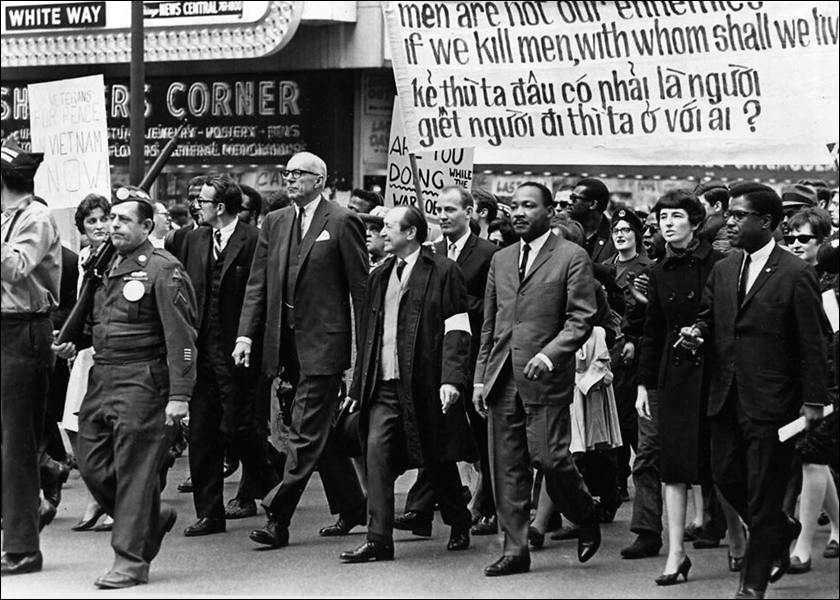

We are not alone in this endeavor. The Civil Rights Movement, a mass movement that transformed people and the U.S. as a whole, offers a model and precedent for progressive struggle in this country. The courageous examples of Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King Jr., and Muhammad Ali, in their stand for the American people and against imperialist wars, came from a broader understanding of war as the antithesis of democracy and as the enemy of the poor.

As inheritors of this history, we must fundamentally reconceive of a new peace movement today as a democratic movement; democratic in that it takes the choice of war out of the hands of the elites and places it into the hands of the people. Peace is the universal issue around which many different kinds of people — including different subgroups of the Korean American community — can come together to know one another, find common ground, work out differences, and develop stronger unity and vision on our own terms.

Peace is also the language through which we as young Korean Americans can rediscover the meaning of our civilization and its contributions to the human family. Peace is the mandate which calls us to love and believe in the American people, of whom we are a part. It is not a coincidence that the media and ruling elite want us to view Trump and his supporters as irredeemably ignorant and backwards, just as North Korea is depicted as inhumane and backwards. Peace urges us to consider that there may be something human in North Korea’s experience of war, hardship, and fierce resilience, which parallels the experiences of South Koreans and from which we can learn. Likewise, peace calls us to question narratives that tell us to distrust our own countrymen. It is time for us to seek out the truth for ourselves. By striving to understand the people of this nation and our homeland, we will know ourselves better, and realize our capacity to rise to the calling of history.

From the peace talks of 2018-19 to the current moment of dangerous escalation, many of us can feel the swelling currents of Korea’s long journey through war and division, reaching us here in the U.S. Each of us is called to reimagine our own stake in Korean peace and reunification from a narrow demand to a broader task of fulfilling the promise of real democracy in America.

America need no longer linger as a lonely empire threatening the world. We can play a role in reforging this nation into a democratic world house of peoples that can join humanity in its strides toward peace and freedom. Time has given us a precious opportunity — a unique moment of possibility in the course of human events. It rests in our hands to decide what we will make of it.