New documentary film Chosen follows five House candidates forged in the fires of Sa-i-gu | By Martha Vicery (Summer 2022)

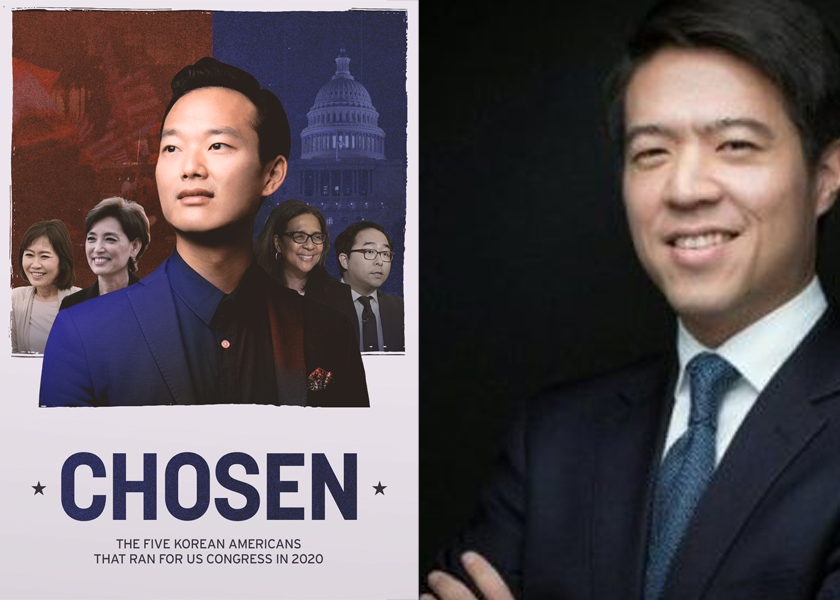

A new documentary film about the five Korean American candidates who won seats for the U.S. Congress in 2020 has been released and is being screened this summer and fall. Four of the five candidates profiled in the film were elected. One, David Kim (D-CA 34th District) will stand for election again November 3 for the same seat he ran for last time, giving this year’s release of a film about a 2020 election a new relevance.

The idea for the film, Chosen, by (former Minnesotan) Joseph Juhn, began in early 2020, when he was immersed in marketing and screening his first documentary film, Jeronimo, about the life and legacy of Korean Cuban politician/activist Jeronimo Lim. That work suddenly came to a grinding halt due to COVID. For him, he said, it was like “the world stopped.”

Juhn had just returned from South Korea, after a three-month theatrical run of Jeronimo. More than 30 screenings had been scheduled across the U.S., in South America, Europe, China and Japan. But in mid-March 2020, all the screenings were cancelled. Juhn returned to Korea, where he lives part of the time “because the cases were still extremely low, and things were still more or less normal,” he said.

In about May or June of that year, John Bolton, the former Trump administration national security advisor, published the controversial memoir The Room Where It Happened. Bolton’s account of the Hanoi meeting between former President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Jong Un Kim was disturbing to the filmmaker. The peace talks failed, according to the Bolton memoir, “because of the self-interests, ideologies, and impulsive decisions of three men – himself, Trump, and Pompeo,” Juhn said. The ridiculousness of how it played out gnawed at Juhn. “How can the fate of the entire regional peace be determined by three top officials of the U.S.?” he remembers wondering.

The idea that Korean Americans’ poor representation in the upper eschelons of U.S. government had something to do with this bleak and fruitless outcome occurred to him, Juhn said. He reflected on how it could have been different. It was about that time that he read that five Korean Americans were running at the same time for the U.S. House (See KQ account Korean Americans in the House, fall 2020 edition). The idea was a hopeful one.

“I knew David Kim,” Juhn explained. “We were both attorneys in New York. We were around the same age and graduated about the same time. He was a pretty well-known entertainment attorney.” At one point, the South Korean government agency Juhn worked for invited David Kim to speak about legal entertainment-related issues, so the two had met in recent years.

Juhn laid out an idea to Kim, that he would follow him and the other four Korean American candidates, to do a documentary film on this unusual election year for the Korean American community. Kim agreed, and Juhn showed up in California’s 34th District, which encompasses Los Angeles Koreatown, one of the poorest districts in the nation, to start filming the Kim campaign.

At the same time, Juhn began contacting the other four campaigns in 2020: The sole incumbent Rep. Andy Kim (D-NJ); Tacoma, Washington former mayor Marilyn Strickland (D-WA 10th District); Michelle Park Steel (R-CA 48th District); and Young Kim (R-CA 39th District). All gave the filmmaker some level of access to their campaigns. From three months of filming, a 90-minute documentary emerged. The editing, in collaboration with expert documentary editor Yong Zong, took about 18 months. The film launched in May.

All the candidates had compelling personal stories about why they were doing the long, hard work of campaigning for office. The film described Strickland’s personal story, beginning with her Korean immigrant mother and her African American father; and Andy Kim talked about the identity crisis of his youth in a majority white city, and how he didn’t want to be seen as Korean during his youth, rather as strictly an American. Despite those beginnings, he embraced his Korean-ness as an adult, and has talked about his Korean background as a candidate and an elected official.

Interestingly, as the only Korean in Congress during the Trump administration, and as a former national security staff member under Obama, Andy Kim expected to be consulted on the 2016 summits between Trump and North Korean leader Jong Un Kim. He relates in the film that he was never asked.

The story also explains how Young Kim worked for many years in the shadow of long-time Congressman Ed Royce, and was involved in many joint U.S.-South Korea official meetings as a translator and interlocutor. With plenty of experience working in Congress, Young Kim is running for the chance to shine at the job Royce vacated.

It also tells the story of Michelle Park Steel, an immigrant, who came to the U.S. with her mother and two sisters, and was raised by her single mom. She experienced her mother being angry and stressed out because of an unwarranted tax bill. When the opportunity came, she ran for and won the top seat at California’s Board of Equalization, and worked in a county elected position as a tax advocate. The film shows Steel’s election day party with enthusiastic unmasked guests in MAGA hats. “No matter what political difference I may have as a creator, her charm, her frankness is irresistible,” Juhn said. “It’s s hard to turn away.”

The districts the candidates ran to represent are also very different from one another. Young Kim and Michelle Steele are both in Orange County, which is an ethnically-diverse area, but has a lot of upper middle class and rich conservatives. Strickland’s district is diverse, but overall progressive. Andy Kim’s New Jersey district is purple, with a mix of conservative and mainly white voters, with ethnically-diverse progressives – he has had to campaign across a broad spectrum, dominated by white voters.

The beginning of the film roots the rise of Korean American leadership in the 1992 riots in Los Angeles, which is various called the Rodney King Uprising, or, in Korean America, Sa-i-gu (literally “four-two-nine” in Korean, which stands for April 29, the date the uprising began). The 30th anniversary of Sa-i-gu was in 2022, which makes the year of the five candidates’ campaigns a significant one.

When Korean American businesses were destroyed by rioters in the spring of 1992, the immigrant entrepreneurs in Koreatown did not have sufficient mainstream leadership or language proficiency to speak for themselves. Instead, the second generation of young adults took charge in telling the Korean American immigrant story in the media, and a wave of new leaders grew out of the second generation as a result of this event. From the first scene of the film, Juhn shows the historical and cultural ties of Sa-i-gu to the emerging Korean American leadership.

David Kim’s story stands out the most of the five candidates. He was also the only candidate who did not get elected. “Yeah, that’s the irony of life!” Juhn said. “In the film, he becomes the primary protagonist who carries the entire narrative. This was partly by choice and partly by reality. Reality meaning that his was the only one who let me have actual free access to his campaign. He was the only one willing to become vulnerable about his personal past, his suffering, his relationship with his parents, and so forth.”

In contrast to more middle-class districts of his fellow Korean American House candidates, David Kim, from the heart of Koreatown, ran to represent a district that is half Latino and 25 percent Asian, with the rest a mix of Black and white. The incumbent in 2020 was Latino Jimmy Gomez, elected in 2017 to fill the seat of Xavier Becerra (who was tapped to become the state Attorney General).

During the 2020 election, many people in Koreatown lost their jobs in public-facing service work, like hospitality and food service. Kim estimated in mid-2020 that some 40,000 district residents had been evicted for non-payment of rent and were sleeping on friends’ couches or in Koreatown tent camps before a federal rent moratorium was imposed to help keep people in their homes and slow the spread of COVID-19.

The David Kim campaign did giveaways of essentials like groceries, and meals the campaign bought from small restaurants to both feed the hungry and support small businesses. It partnered up with an organization to pilot a small grant to give guaranteed basic income to a small number of families and track the progress. One of Kim’s platform policies is an intent to champion a guaranteed basic income nationwide.

The film shows David Kim shouting in English, Korean and Spanish from street corners in Koreatown as he campaigns through the hot summer of 2020. His staff promotes the campaign with posters and by spray-painting campaign signs on graffitied walls and sidewalks. He holds press conferences outdoors, often with a bullhorn.

In the film, elder leaders in the Korean community criticize him for not leaning on the Korean American community organizations for support. There is tension in that Kim feels he is criticized by his immigrant parents, particularly his father, who is a pastor of a charismatic Korean Christian church. As an out gay man, Kim is obviously weighing the pros and cons of Korean American support, and the risk that trying to get the approval of the Korean community may be a lost cause. The film also describes David Kim’s fraught relationship with his parents, particularly with his father. Kim is both thoughtful and honest about his past and family history in a way that shows the candidate’s raw courage.

That David Kim is running again in 2022 gives this film an immediacy and flavor of an unfinished story. Per California law, the two top vote-getters in the district will face off against each other, regardless of their political party. As in 2020, the November face-off could again be between two-time elected incumbent Jimmy Gomez and David Kim.

Juhn said he has had the timing in mind in terms of the film release, “but I did not try to be partisan or want this to be a campaign film for David.” The draw of David Kim was his first-time candidacy and his willingness to give the film crew full access to his campaign.

“My inclination was that David’s story became like the essence of why one wants to run for politics,” Juhn reflected. “He had that kind of sincerity in his run, as imperfect as that may sometimes appear. I appreciated and respected that about him, and I hope that is reflected in the film. Also it was not my intention to vilify any character for their views. I wanted it to be fair.”

Juhn credits his film editor Yong Zong for setting a reasonable production schedule and getting the film out the door in about 18 months. The distribution process, always the hard part for independent filmmakers, has gone slowly and with difficulty for Juhn so far. “Coming up with enjoyable, decent product is challenging enough,” he said. “Selling that product to some of these bigger platforms really does require the right connections and the right subject matter, timing and everything.”

The film did well in South Korea, running in the Jeonju International Film Festival and at the Diaspora Film Festival in Incheon. Private screenings are now scheduled for Chicago October 12, and also for Boston, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Atlanta. Juhn has applied to and is hopeful that the film can be screened at the Twin Cities Film Festival, which will begin October 20.

Juhn is relieved that in-person audiences are back – virtual film festivals are just not the same. The sting of cancelling his full schedule of screenings for Jeronimo is still very much with him. He is hopeful that his promotion of Chosen will be very different. “That 20 minutes of fame?” he said, referring to the director’s chance to talk after a screening. “Yeah, to present to a roomful of complete strangers and have them emotionally engage. It’s a sweet feeling.”

Chosen has a Facebook page, with a trailer for the film at: https://www.facebook.com/CHOSENdocumentary/