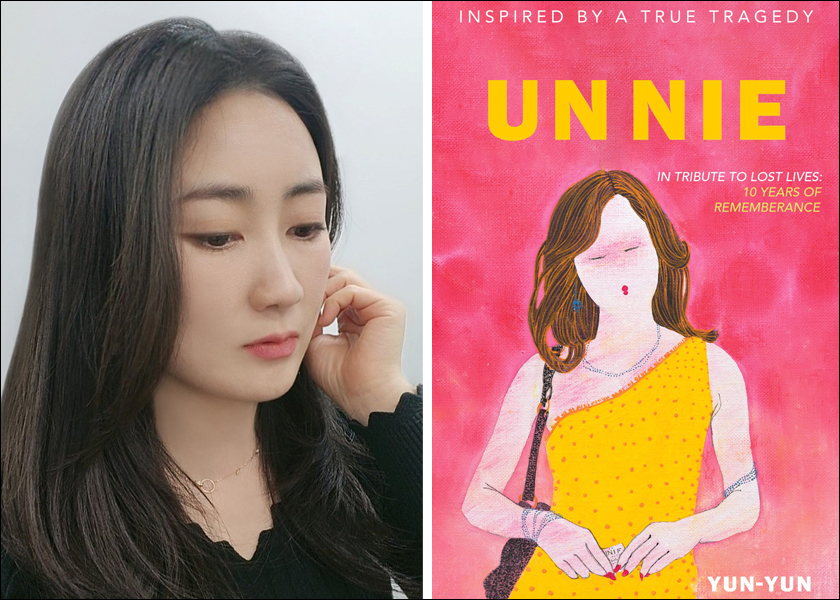

Author interview: Novel Unnie revisits the Sewol ferry disaster, 10 years on

The raw grief of a tragic ship sinking that killed hundreds of people 10 years ago in Korea, as seen through the lens of one family whose eldest daughter died on board, is the topic of an emotional novel entitled Unnie – In Tribute to Lost Lives, 10 Years of Remembrance. First-time novelist Yun-Yun sensitively imagines the tragedy from the perspective of a younger sister of one of the victims.

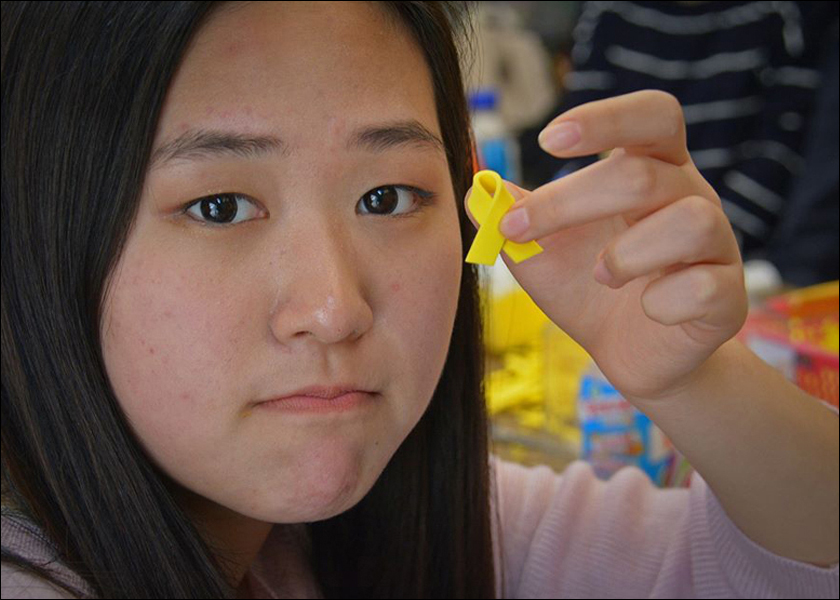

April 16 is the 10th anniversary of the 2014 Sewol ferry sinking, in which 304 of 476 passengers died, 250 of whom were high school students from Danwon High School, and 11 victims were their teachers. The ferry was bound for Jeju Island, off the southern coast of South Korea. It started out the northwestern port of Incheon, but it foundered and sank off the coast of Jindo Island in southwestern South Korea.

The horror of the tragedy, as it played out on international news, was exacerbated by the very late and inadequate rescue of only 176 passengers. The rest drowned onboard, mainly because they were instructed by the ship’s crew not to evacuate the ship. While fishing vessels and other boats circled the sinking ferry, expecting lifeboats to be deployed, there were very few to rescue because most passengers obeyed orders and did not leave the ship. More than half of the survivors were recovered by fishing boats and other commercial vessels that came to the scene; the Coast Guard was ostensibly in charge, however, no organized rescue effort materialized.

Yun-Yun captures the impossible predicament of a family grieving for its eldest daughter (an elder sister in Korea is called unnie by her younger sister) over many months, and their lonely experience as the last family waiting for their loved one’s body to be recovered. During the same months following the tragedy, information came to light in a perfect storm of tragedy: The wrong and contradictory information given to the waiting families; the lack of regulation and inadequate safety and rescue procedures; and the incompetence, political corruption and graft involved in South Korea’s ferry industry.

The Sewol ferry sinking and its aftermath, a slow and painful disaster that played out over several days, was followed by investigations of numerous governmental institutions, up to the level of then-President Geun-Hye Park. Park was later forced out of office by a national daily public demonstration (dubbed the Candlelight Revolution). It has been theorized that the political debacle of the Sewol was the beginning of the end for Park.

Trials of the ferry crew for murder, follow-ups of the bureaucratic faults that allowed the ferry company to overload its vessels and dodge safety inspections, and various other investigations played out over many months after the sinking.

It was later found that the ferry company had ignored several complaints by the captain that the steering mechanism had problems. It was also found that the ferry had been redesigned to accommodate more passengers and cargo, but that the weight redistribution in the redesign made the vessel unstable, and that it was routinely overloaded. Possible contributors to the ferry’s capsizing ranged from malfunctioning of the steering mechanism to issues linked to excess weight and top-heaviness of the ship. It was found that the Coast Guard should have taken responsibility for search and rescue at the site, but failed to do so.

The author’s emotional journey

The author, who lives in South Korea, wrote an emailed response to questions and preferred not to do an oral interview. For Yun-Yun, writing the book was “a profound emotional journey, one that brought me to tears countless times,” she wrote.

After becoming a teacher and reading novels by authors from all over the world, she wrote, she started thinking about what she would write about in her own novel. She was mulling over some ideas for inspiration. “Then the Sewol ferry accident occurred, drawing me into its heartbreaking stories and fueling a desire to share these stories with the world,” she recalled.

As a teacher, she said, the tragedy of it struck her deeply. When she sees the joy and energy of her own students, it inevitably reminds her of the hundreds of students whose lives were cut short. Her objective in writing the book, she said, is to “unite everyone in honoring the memory of the departed and offering solace to the mourning families.”

The name Yun-Yun is a pseudonym. The author stated that she is concealing her real name because she cherishes privacy, and does not want to be a public figure. She wrote that she also wants readers’ attention to be drawn to the story of the novel and the remembrance of those lost in the disaster, and not to her.

Novelizing a real event in history, particularly such a controversial one, is to wade into some turbulent waters. The author said she realizes she is limited in writing the story from the perspective of just one fictional person, the sister of a victim. In attempting to give some insight into the events and the pain experienced by one grieving family, she commented “there are inevitably those whose stories remain untold.”

The author’s note, preceding the first chapter, reflects Yun-Yun’s caution about what she can accomplish in a novel. Thousands of people were involved in the disaster, and there are so many varied stories of the abrupt ending of many promising young lives, and what loved ones suffered as a result.

Recently, she remarked, the tragedy “has become something of a taboo topic in Korea.” She noted that the event “that once united the whole nation in grief” has been broken over time along political lines. Unfortunately, it is now “giving rise to numerous rumors and myths, even conspiracy theories,” she wrote.

What is true depends on the storyteller, Yun-Yun reflected “The world is full of contradictions disguised as truth. Is there such thing as an ‘absolute truth? Truth within oneself may not be truth within the other. In this sense, I can’t say this book is the exception,” she pointed out in her author’s note.

She observed that everyone experiences different impressions of stories we hear, even of ordinary incidents in our daily lives. The novel Unnie is a mixture of reports of a historical event with her own memories, upbringing and experiences. It adds in fictional and memoir-like reflections.

It was not an ordinary writing project for the author. “Throughout the writing process, I couldn’t shake the feeling that writing this novel was my destiny. Surprisingly, despite it being my first attempt, the narrative flowed effortlessly,” she wrote. She was able to do an almost “seamless blending of my own life experiences with those of the families impacted by the tragedy.”

In addition to reading everything she could about the tragedy, the author also viewed some videos documenting the sinking. She recalled in particular a video of the faces of parents and other loved ones of the passengers who were assembled in a room in Jindo, the closest port to the sinking ship. The people waiting were initially told that all the passengers had been saved. This was “a shocking and deeply troubling error,” she wrote, and “the origins of this misinformation remain a mystery until now, marking it as one of the worst instances of false reporting.” After a few hours had passed, that report was changed. The waiting families were then told that an unknown number had been lost and a rescue effort was ongoing.

There was a rollercoaster of emotions in the faces of the waiting people caught on some of the videos she watched “from relief to shock, [that] brought me to tears,” she recalled. “I had to repeatedly watch the footage to capture every detail – their expressions, the weather, the color of the sea, etc. It was an incredibly painful process.”

One truth that rings out throughout the book is the emotional truth, particularly the black grief of younger sister, Yun-young, as she attempts to come to terms with the loss of her elder sister Mi-na with almost no support. Her parents are seemingly too grieved to take notice of what she and her younger brother are suffering. Brother Ji-ho, a teenager, is not demonstrative and won’t express, even to family members, the depths of his grief. The parents are also absent from their home, spending a lot of time in Jindo, waiting for the recovery of their daughter’s body, leaving brother and sister at home to cope on their own. Adding to their bottomless grief, Mi-na’s body is never recovered.

At one point, a smelly, sodden and damaged suitcase belonging to Mi-na is delivered to their home. The author writes a tender description of the mother opening the suitcase, and talking to each muddy, salty item as she takes them out, hand-washes them and hangs them to dry outdoors.

Eventually, three years after the accident, the Sewol is exhumed from the deep and searched; it is determined that Mi-na’s body is not aboard. The family decides to have a funeral ceremony with an empty coffin in which they place flowers and personal items from Mi-na’s life. The coffin and its contents are cremated and the ashes buried in a memorial park for the victims. It is the most bitter kind of closure possible.

A conversation across time

Another level of grief that the author delves into is the lost opportunities for life’s joy that the young victims were deprived of, since Korean high school students are typically expected to study non-stop for years in order to get the highest possible grade on an important standardized test.

In the beginning of the story, the reader follows younger sister Yun-young on a quest she embarks on after the disaster. She is on a search to discover more about her older sister’s life. Yun-young goes back to the neighborhood where Mi-na lived while studying for her teacher’s certification test. Yun-Yun commented that, for that description, she drew from her own experience living in Noryangjin, Seoul, a neighborhood populated by cram schools for people taking various civil service exams.

In addition to the study schools, there are dismal dormitories where students live in one-room apartments with shared bathrooms. Cheap street food stalls line the streets, as well as convenience stores, health clinics, mental health counselors, pharmacies, and many other services a student would need to live on their own.

“It is where Unnie — or essentially, me — secluded herself to tirelessly prepare for the national exam to become an English teacher,” she explained. There is an image of Yun-young, on her quest to know her missing sister, trailing after an ethereal figure of Unnie as she walks up the staircase of her academy. The image is poignant “but it became even more so when Unnie casts a cheerful smile over her shoulder and motions for Yun-young to follow. In that moment, my own vision blurred in sync with Yun-young’s,” the author reflected.

For the author, Unnie is the older self, encouraging the younger self, Yun-young, to persevere; it is also a parallel of the kind of encouragement the author says she, as a teacher, tries to give to her own class of high school students. .

The author added “Initially, I hadn’t fully grasped the significance behind the choice of the teacher’s name ‘Park Mi-na.’ It simply felt like a straightforward, easily accessible name for foreign readers. However, when questioned about its origin, a revelation struck me: ‘Mi’ translates to ‘me’ in English, while ‘na’ signifies ‘me’ in Korean.”

The dim and busy cram-school neighborhood, with its tired but hopeful inhabitants, is an effective setting for the start of the story. It also provides insight into the drudgery of the Sewol students’ lives in the years prior to the tragedy and is a reminder that the vacation they were beginning on the fateful day of the accident was intended to reward them with some well-earned fun and joy. It is also seemingly an oblique commentary on the educational system that makes such neighborhoods necessary.

Yun-Yun noted that she has struggled her whole life with “self-imposed expectations,” she wrote. “Since childhood, I’ve shouldered the burden of striving for high standards and deferring happiness until specific milestones were attained. This mindset persisted into adulthood, even after achieving my dream of becoming a teacher amid fierce competition.

“It took me a long time to realize that the child you once were only grows physically to become the adult you are today,” she added. “So, as an educator, I began to see instilling in my students the importance of finding joy in their pursuits and fostering a positive self-relationship as my primary responsibility.” In her opinion, she commented, a positive mindset is “essential not just for achieving favorable results but also for discovering fulfillment and happiness in life.”

The author wrote that “I contemplated whether my life’s path had led me to pen this book.” Like in the story of Yun-young and her family, the author once lived in the U.S. for a few years as a child with her family. She has vivid memories of that time, and the experience had a significant impact on her life. “Not only did it enable me to write this story in English, expanding its accessibility, but it also enriched the narrative with the depth of my experiences there,” she remarked.

Who is Mi-na and who is Yun-young?

As an older sister with both a sister and a brother, like the character Mi-na, the term “Unnie” carries significant weight for the author. In her role as the oldest sister, the author said, her life was full of additional responsibilities, including “caregiver for my younger siblings from a young age, prioritizing their needs above my own. I’ve often found myself taking on parental responsibilities, nurturing and getting them through life’s hardships.” In contrast, she said, she had little support from others. “I rarely confided in others about my problems; instead, I always felt compelled to find solutions independently.”

In the U.S., she recalled, she needed to take on even more responsibilities as a cultural and language translator for her parents about important matters. She recalls translating one time for her parents at a parents’ meeting held at her sister’s school “despite my limited English proficiency in seventh grade,” she admitted.

Concerning her younger siblings, the author believes there is a significant difference “in how they view me, compared with how I see them,” she observed. They are “wonderful siblings,” she said, but they have grown apart from her and seemingly live their own lives easily, while she struggles, even now in adulthood, to prioritize her own needs above theirs.

The writing of the novel provided a “source of comfort,” she reflected, “like having a sincere conversation with myself across time.” It gave her a sense of “solace and understanding” that had been missing in her life, she wrote.

Holding a place for the victims

It was not an ordinary writing project – the author expressed this in a variety of ways. Choosing a real event as the basis for a novel made it a more unique backdrop than most novels; and choosing such a devastating event that changed a whole nation made it challenging to describe. In addition to that, there was the tragedy of the many hundreds that needlessly died. Capturing the loss of even one of those lives made this novel a difficult and often painful writing project.

In a spiritual sense, the author hopes her story can be another way to keep the memories of the victims alive, even if not by name. The many victims felt like part of her team in the creation of this story, particularly the students who perished. She feels that the students “have been with me every step of the way throughout the writing process, and will continue to support me through every hurdle encountered on the journey towards publication.”

Certain dreams appeared and meaningful incidents unfolded during the writing of the book that the author views as having been revealed to her by those students. “Indeed, they have been my silent collaborators, co-authoring the book alongside me to ensure their stories are not forgotten and are brought to light.”

Unnie – In Tribute to Lost Lives, 10 Years of Remembrance is published by Libre Books and is available from various booksellers.