Tracing the newspaper’s impact on my life as an adoptee | By Tom McCarthy (Spring 2022)

I didn’t know what it meant to be Korean. I knew I was Korean, but I didn’t know what it really meant to be Korean. Korea was just a place I came from, a place with good food, a place written about in the pages of a newspaper whose seasonal editions were readily available on a coffee table or magazine basket in our house.

Under the big block letters that spelled out KOREAN QUARTERLY were words that related to me: “adoptees,” “Korean Camp” and “birth family search” among others speaking to the Korean American community at large, but I didn’t really care, not then.

It wasn’t until 2002 that I began to care. When Korea was announced as the co-host of the World Cup that year, my dad decided that we were going to wake up to see the Korean games broadcast live. Just three matches, he was certain; Korea was in a group with the strongest U.S. team yet and the golden generation of Portugal. Surely Korea would be knocked out in the group stage, disappointing but not unexpected.

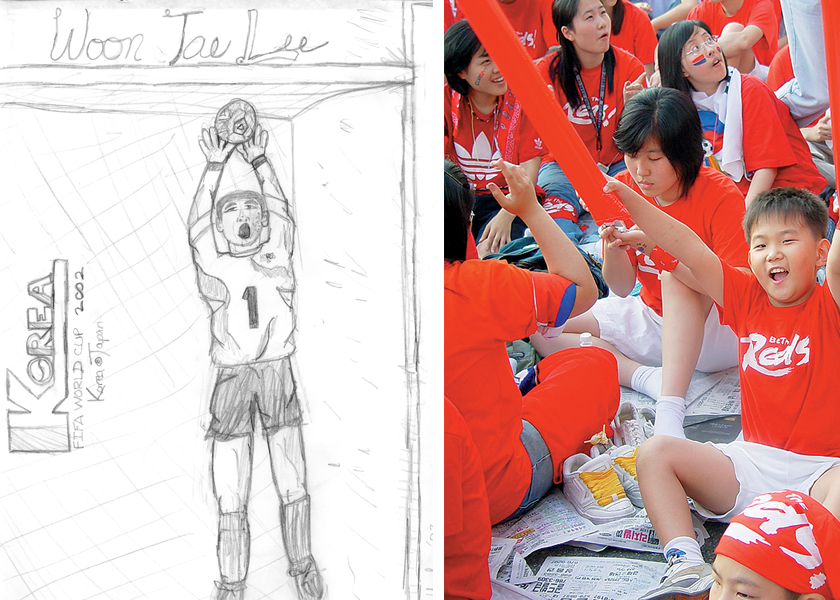

As Korea won, tied, and then won, won, won, my Korean-ness reached fever pitch. In the aftermath of the World Cup, I voraciously consumed everything Korean, from food to books to music. My sketchpads were filled with drawings of Korea’s World Cup heroes, some of which my mom sent to be published in Korean Quarterly’s art section. It was as if the Korean wave had crashed down precisely on our house alone.

I also began to wonder — really wonder — what it meant to be adopted from Korea. Having outgrown the children’s book When You Were Born in Korea, I needed another source of light to guide my way. I found it in Korean Quarterly. Perhaps unbeknownst to my parents, I began to read all the articles I could, from past editions to present, about adoptees: Searching for birth parents, about how adoptee organizations had started around the U.S., about going to Korean camps… And about how adoptees were moving to Korea.

The next year, our family took our first trip to Korea. The sights, sounds, and smells I had read about in numerous Korean Quarterly articles came alive, experiences imprinting themselves on my impressionable mind. I was entranced, captivated by the vibrance of the markets, the tremor of rush-hour traffic and the pulsing luminescence of the neon signs lighting our way.

First discovered in the pages of Korean Quarterly, I was now witnessing these experiences in person, and they called to me, all of 13 years old, like a siren song drawing me toward something mysterious and foreign, but something I desperately wanted to be a part of. Toward the end of our trip, I casually announced, “I’m going to live here one day.”

Years passed and my zealous fervor for Korea waned as I found new interests and new identities to try out. Even so, I kept coming back to Korean Quarterly, if only to re-live that week when I was one of them, the people in the articles and photos splashed across the pages.

As I prepared to graduate college, and with little sense of direction, my dad mentioned that Korean universities had language programs, and there were scholarships for adoptees. I remembered reading about that program in a Korean Quarterly article about Global Overseas Adoptees’ Link (GOA’L), a group started by adoptees in Korea, but that once-burning ambition from my adolescence had since faded away. “Why don’t you try living in Korea for a year?” my dad proposed. “If you don’t like it, you can always come back earlier.”

A month later, I landed at Incheon airport at 9:30 at night with one suitcase of clothes and a printout of directions to the adoptee guesthouse where I had booked a room. I only knew one person in the entire country: A Korean friend I hadn’t talked to in over five years, and he didn’t even live in Seoul. I had done almost no preparation for my big adventure, not even looking at a map of the city. In a metropolis of 25 million people, I was completely alone.

My vision began to blur as I boarded the shuttle bus into Seoul, accompanied only by the driver and a middle-aged man who promptly fell asleep, undoubtedly relieved to be home.

On the 90-minute ride from Incheon airport to central Seoul, my anxiety grew steadily as I stared out the window at the passing lights of Songdo, Gimpo, Digital Media City… And I thought to myself, “I just made the biggest mistake of my life.”

My adolescent naivete had lured me to my demise. As I laid in bed on my first night in Korea, I was wholly prepared to wave the white flag and return home a failure. The next morning, I decided to spend a week getting some interesting photos and then reschedule my return ticket. That first week turned out to be a solitary one; everyone in the guest house was on summer holidays between language school terms. With no one to shadow like a helpless puppy, I had to venture out on my own, chasing memories of this city that had beguiled me 10 years earlier.

After hitting the main sights recommended in my tourist book, I needed a new source of inspiration: Why not the publication responsible for getting me into this mess, Korean Quarterly?

Perusing the website, I found the occasional article about a cultural event in a park years ago or a foodie guide to Gwangjang Market, but not much suited to a mad dash through the city for a week, no recommendations on how to fake a fun time 6,000 miles away from home.

What was there, however, were articles illuminating a different experience altogether, the one that ignited my Korean daydreams as I first leafed through the pages of the newspaper a decade earlier: Adoptees who had lived in Korea for years. Articles covering the goings on of GOA’L year-round, updates from adoptee activist groups gathering for their regular barbecue dinners, and personal essays encapsulating the joyful resilience required to build a life here.

Suddenly, Korean Quarterly gave me something else: Hope. If these guys can do a decade, I reasoned, I can survive a year.

After a week, the guest house was bustling. Adoptees from all over the world converged in the kitchen, sharing stories about their trips outside Seoul and making weekend plans. As I made friends and rediscovered this city and country through people like me, I began to feel more “at home.” The weeks bled into months as I began to live out my once-dying dream. I chose favorite restaurants and bars, corrected public transit routes proposed by others and met more and more adoptees who shared my same dream. Every once in a while, my mom would mention something she read about in the latest Korean Quarterly and ask if I had been there, tried that. “No,” I’d reply. “I’m busy, and this is just my life now. I live here.”

The months culminated in a year, 365 days of living in Korea. At the year mark, I was past the point of no return. The dream was alive again. The days passed in a blur, a steady routine punctuated by the occasional highlight. I was now one of the people I had read about in those Korean Quarterly articles. Despite the inevitable revolving door of friends returning to their adoptive countries, I found myself settling in, coalescing comfortably with the permanent adoptee community. I joined the adoptee soccer team (kind of), started working at an English academy run by adoptees and attended GOA’L events.

After apparently accepting my decision to stay longer, perhaps hoping it was just a phase, my parents sent my middle brother over to visit. With no signs of this phase abating, they came themselves with my youngest brother a year later. Once it was clear that this was where I wanted to be, we took turns visiting each other, them to Korea and me to Minnesota. Each night as I slept in my childhood bedroom, I dreamed of “my city, my home.”

My mom’s mentions of Korean Quarterly articles ebbed the longer I was here. Maybe she assumed I was already on top of their Korean coverage, or maybe she just figured I didn’t need anyone’s advice. But every once in a while, a Facebook friend would share an article from the latest issue and, almost instinctively, I would read it.

Now the newspaper was delivering stories from my past life: News from Minnesota, the successes of adoptees and Korean Americans in every sector of the economy across America and updates on political mobilization by the two communities. Scattered among those articles were pieces about Korea: A photo essay from a festival or an editorial on support for adoptees who re-emigrated.

Like a biographer stealthily tracking me from my birth to my adoption and my return to Korea, Korean Quarterly has been, all this time, narrating my life, providing a gateway into my past, my present and my future. After almost nine years, it’s my turn to be the voice from Korea for the newspaper’s readers, illuminating one perspective of the adoptee experience in the land of our birth as the seasons change.

Maybe you’ll find yourself flipping through the pages of a Korean Quarterly issue when something catches your eye: A photo of a Busan beach, an article about Jeju orange farms or an essay about a birth family search. Maybe it will awaken something inside you, something you didn’t know was there, now calling out to you like an echo from the top of Bukhan mountain.

And maybe one day, you’ll find yourself sitting on the shuttle bus from Incheon Airport heading toward the gleaming lights of Seoul as they beckon you home… And you’ll think to yourself, “I just made the best decision of my life.”

Happy 25th birthday, Korean Quarterly. Thanks for everything.

Tom McCarthy’s World Cup drawings were his first contributions to KQ. These days, 20 years later, he submits essays from his Seoul resident’s perspective, film reviews and other articles. From 2020 to 2022, he was the media relations project coordinator for Global Overseas’ Adoptees Link (GOA’L), an advocacy and human rights organization by and for Korean adoptees located in Seoul. He is now the copyeditor and anchor of the English edition of KBS WORLD Radio News.