A look at the producers of a recent PBS documentary, and its bias in relating Korean modern history | By Tim Shorrock (Winter 2024)

“Growing up in North Korea, you learn nothing of the outside world.” – Director Madeleine Gavin, boasting with former high-ranking CIA operative Sue Mi Terry about their film Beyond Utopia, which was passed over for an Academy Award nomination.

Remember The Interview, the satirical Seth Rogen film depicting the assassination of North Korea’s leader Jong Un Kim by two CIA operatives, which was released by Sony Pictures on Christmas Day in 2014? You should. When North Korea allegedly hacked Sony in an apparent attempt to sabotage the film, then-President Barack Obama, whose top national security aides had previewed the film, led an unprecedented campaign with Michael Moore and other Hollywood liberals urging Sony to release it.

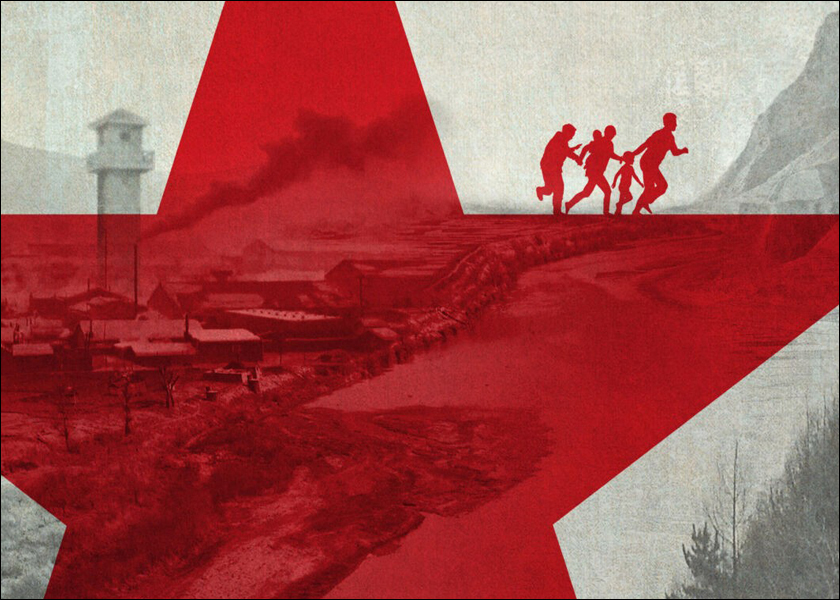

After millions of gullible Americans followed their leaders into theaters across the country, Thor Halvorssen, a right-wing Venezuelan activist based in New York, led a flamboyant campaign by North Korean defectors in South Korea to illegally air-drop DVDs of the film into the North using hot-air balloons launched from a spot just south of the DMZ. That, in turn, sparked a furious response from Kim’s influential sister Yo Jong Kim, and inflamed domestic politics in South Korea, with repercussions lasting until today.

Now, 10 years later, at a time of intensifying tensions on the Korean peninsula, Halvorssen has forged an alliance of Hollywood liberals, prominent North Korean defectors, and a former U.S. intelligence official to produce another film. The intent is seemingly to undermine Kim’s North Korea, and to prime Americans for a regime change, which the South Korean right has sought after, along with the Pentagon, and elements of the U.S. national security state.

Halvorssen’s partners are Sue Mi Terry, a former high-ranking CIA official with the Bush administration, who has been affiliated with the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), and the government-funded Public Broadcasting System (PBS). Two executive producers, Hannah Song and Blaine Vess, work with Liberty in North Korea (LINK), which claims to operate what it calls an “underground railroad” for North Korean defectors and frequently briefs the U.S. government about the DPRK. Another producer, defector Hyeonseo Lee, works closely with Halvorssen’s Human Rights Foundation (HRF).

The result is Beyond Utopia, a documentary film claiming to be “the gripping story of families who risk everything escaping North Korea.” The film, directed by Madeleine Gavin, is told from the perspective of a Seoul pastor who helps North Koreans stranded in China get to the South. It and premiered January 9 on PBS’s Independent Lens series.

Gavin’s January 14 interview on CNN was the first shot of an expensive media campaign that producers hoped would climax on March 10 with the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film. But they failed to convince Academy members responsible for viewing the eligible films that it was worthy of an Oscar.

Halversson’s Human Rights Foundation (HRF), CSIS, and its other producers at Ideal Partners Film and LINK have been pushing the film relentlessly on Twitter (now X) and on their own websites as the must-see documentary of the awards season. Until the Oscar rejection, the campaign was a smashing success. Last year, the film captured the Sundance Film Festival Audience Award, and it has been rapturously reviewed by the Washington Post, the New York Times, the Guardian, and nearly all of the Hollywood press (for now, it can be viewed, in its entirety, at the PBS Independent Lens website here).

But their stories are not new to Americans. Thanks to the prominent defector Yeonmi Park, who serves on the board of Halvorssen’s HRF, the U.S. public has been fed a steady diet of frightening and often exaggerated tales depicting North Korea as a cruel, demonic state that despises its own people and uses extreme measures to control them. Park’s stories, usually accompanied by well-timed tears and a quivering voice, have made her a media darling in a country where many people, liberals and conservatives alike, simply love to hate North Korea.

In 2014, the New York Times was one of the first publications to fall for Park’s fantastic stories. As the North Korean celebrity du jour, Park’s appearances on media outlets such as NBC News and the popular podcast The Joe Rogan Experience have drawn millions of viewers. But under scrutiny, many of her claims have been found to be false, as the Washington Post, another early champion of Park, discovered in a devastating takedown in 2023.

Park’s unproven descriptions of North Korea has made her a subject of ridicule on social media, especially among Korean Americans. Recently, her embrace of the tenets of the MAGA movement, particularly its opposition to “DEI,” or diversity, equity and inclusion, has made her a big Elon Musk fan. In December, she was a prominent speaker at a Turning Point USA conference with Ted Cruz, Dennis Prager, Charlie Kirk and other MAGA reactionaries.

The producers of Beyond Utopia seem to have taken a lesson from Park’s experience and her descent into a far-right ideology. The film is designed to pull on liberal heartstrings by depicting the struggles of everyday North Koreans as they make their way through China and Southeast Asia to South Korea and beyond. According to Gavin, Beyond Utopia was put together with video from hidden cameras provided to her by the film’s hero and star witness, Pastor Seungeun Kim of the Caleb Mission, a South Korean religious organization that helps North Koreans make the difficult journey from their home to South Korea.

With Kim’s footage, the director told the media website Deadline, she “started to feel the pulse and heartbeat of these people” by “cracking open North Korea and what it’s like.” To gather information, she claimed to have scoured the internet and “read everything she could get her hands on” about North Korea “in every language [and] every country.” Her research, she claimed to CNN, contrasts sharply with people in the DPRK, who grow up learning “nothing about the outside world.”

Judging from Gavin’s historical account of Korea’s division and the Korean War, however, North Koreans know far more about the American role in Korea and the “outside world” than Gavin herself will ever know about Korea.

Her vaunted internet skills appear to be skewed to the far-right and hand-fed to her by Terry, the former CIA operative who produced the film. She doesn’t investigate what happens to defectors when they get to the South, or why some of the 35,000 defectors in the ROK choose to return to the DPRK. And throughout the film, it’s obvious she has missed the large volume of material available on the internet and any public library about the Korean War, the origins of North Korea’s nuclear confrontation with the U.S., and the economic conditions that have led many of its citizens to flee.

That point was made forcefully in a January 7 “open letter” to Lois Vossen, Executive Producer at Independent Lens, from three prominent Asian American filmmakers, Deann Borshay Liem, Hye-Jung Park, and J.T. Takagi.

“We are concerned that Beyond Utopia presents an unbalanced and inaccurate narrative about Korean history and North Korean society,” they wrote in the letter, which they also posted on the media platform Medium. “While the film’s verité sequences of the Roh and Lee families’ plight are compelling, noticeably lacking is any mention of the ongoing impact of the Korean War and U.S. policies that have destabilized the livelihood and well-being of North Korea’s people — factors that cause families like the Rohs and Lees to leave the country.”

In their letter, Liem, Park, and Takagi explain how the film ignores the impact of the Korean War and the decades-long strategy by the U.S. government to undermine and weaken the North Korean state.

“Beyond Utopia implies that identifying brutalities and helping North Koreans flee to freedom are the only solutions to North Korea’s human rights violations,” they write. “To be sure, the North Korean government, as all countries which ascribe to the United Nations charter, should be held accountable for breaches in human rights. But U.S. policies that have destabilized the human security of the North Korean people for the past 70 years must also be held accountable. We believe that diplomacy, engagement, and building trust are more sustainable and effective ways to improve the lives of everyone on the Korean Peninsula.”

A transcript of the film’s history section underscores how much Gavin and her CIA-bred producer stray from the truth about North Korea. In a sidebar that follows this article, I’ve posted a few excerpts from Gavin’s narration, followed by my own analysis showing the extent of the director’s deliberate obfuscation of Korean history and America’s role in it.

Most problematic, in the view of its critics, are the way North Korea’s economic ills and current conditions are approached by Gavin and the producers. For example, the devastating impact of U.S. and UN sanctions on the civilian population is not even addressed. As the authors of the open letter told PBS’s Independent Lens, “U.S.-led sanctions underpin the difficult economic conditions portrayed in the film. North Korea is one of the most heavily-sanctioned countries in the world.” Kee Park of the Harvard University Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, a neurosurgeon who has trained doctors and regularly performed surgeries in North Korea, has called these sanctions ‘warfare without bullets.'”

The authors also take issue with a sequence in the film about North Koreans “coveting human waste.” This, the directors wrote, “is simply callous. Other countries also use human waste as a fertilizer and for the production of methane gas. In the case of North Korea, sanctions severely limit the country’s capacity to import oil, fertilizer, and even spare parts to run farm equipment. In the absence of this information, the sequence promotes derision rather than empathy for the plight of ordinary people struggling to get by with extremely scarce resources.”

I can personally attest that the use of human waste for fertilizer was very common in South Korea and Japan during the years I grew up there during and after the Korean War (the photo above was taken by my father in Seoul in 1959). Anyone who lived in Korea at the time remembers the “honey bucket men” who would pick up the waste and deliver it to farms (once, walking in rural fields near my house in Seoul in 1960, one of my siblings had the awful experience of falling in a pool of human fertilizer, an experience engrained in our family’s collective memory). To make its use a key point in ridiculing North Korea is simply racist.

In her response to the open letter, Gavin, the director, stated that her film “

attempts to give voice to North Koreans, people who have been largely unseen and unheard by the outside world for more than 75 years. Our goal was to honor the families that trusted us with their stories and to provide audiences with a window into Pastor Kim’s lifelong dedicated work. We have been humbled and gratified by the wonderful reception that the film has received.

She adds: “Our film does not set out to present a comprehensive history of the Korean War, or the development of the North Korean state.” However, Gavin’s factual misrepresentations, intentional or not, should raise serious questions for any documentary seeking Hollywood’s highest prize for truth-telling. So, too, should the politics of the film.

The politics of regime change

Like The Interview, the film Beyond Utopia is intended to build public support in the U.S. for outside intervention — preferably U.S. intervention — in Korea. This kind of support would be important if there should be another Korean War, or in the unlikely scenario of a political collapse in the North.

That theme was underscored last year by the Seungeun Kim, the South Korean pastor whose work is a focus of the film, in an interview with Politico. “I want the regime to collapse,” he stated. Asked what happens in those circumstances, Kim replied: “I’m afraid that it’s going to be chaotic… They’ve been living under control, like brainwashing. They never really make their own choices.”

Kim added “So when this regime collapses, people won’t know what to do. It will be all chaos. We need to be prepared for how to control the chaos (my italics). But my assumption if they collapse is the Chinese government is going to take over first. If they collapse right now, the Chinese will try to take over faster than anybody else. I think China would try to manipulate and use the North Korean situation to deal with the United States.”

That, of course, is a scenario often discussed by U.S. national security officials. As I reported in 2020 in Responsible Statecraft, Avril Haines, President Biden’s director of national intelligence, has publicly argued that any U.S. pressure campaign against North Korea must be accompanied by “intensive contingency planning” in preparation for a “collapse” of the Kim regime. Such planning, she emphasized in a talk at the Brookings Institution in 2017, “must be done not only with [South Korea], but also with China, and of course Japan.”

The film’s executive producer Thor Halvorssen, has shown through his actions how much he believes in regime change. His record of political intervention and interference in South Korea on behalf of North Koreans who he believes are craving American intervention (and his support) is a story in itself. It’s important to understand this man, who undoubtedly wished to be one of those accepting an Oscar, if his film had been nominated.

Halvorssen is a member of the Venezuelan aristocracy. He is the first cousin of Leopoldo Lopez, a prominent right-wing politician in Venezuela, and a major supporter of Juan Guaido, the right-winger usurper once recognized by the U.S. government as the de facto leader of Venezuela. Both Lopez and Guido have been major recipients of money from the U.S. government’s National Endowment for Democracy, which has also funded many North Korean defectors.

HRF often speaks through its chairman, Garry Kasparov, a fanatically-anticommunist opponent of Russian leader Vladimir Putin. Not surprisingly, Kasparov disapproves of any attempt to end the Korean War through dialogue, as South Korean President Jae-in Moon attempted in 2018, when he invited top officials from Jong Un Kim’s government to the South for the Winter Olympics.

Moon “claims to be using the games to foster goodwill, but the reality is that the Hermit Kingdom has taken this opportunity to stage one of history’s great whitewashing operations,” Kasparov wrote in the Washington Post (he was wrong: the talks led to two years of relative peace and the suspension of North Korea’s missile tests and U.S.-South Korean joint military exercises).

Halvorssen founded the Human Rights Foundation (HRF) in 2005, to “unite people — regardless of their political, cultural, and ideological orientations — in the common cause of defending human rights and promoting liberal democracy globally,” according to its Internal Revenue Service Form 990 tax statement. Those forms show that HRF received over $68.8 million in “public support” between 2017 and 2021, a princely sum for any non-profit.

The foundation hasn’t disclosed the source of the money since journalist Max Blumenthal disclosed in The Electronic Intifada that the HRF received nearly $800,000 from the extreme-right (and Islamaphobic) Donors Capital Fund and $325,000 from the conservative Sarah Scaife Foundation from 2007 to 2011.

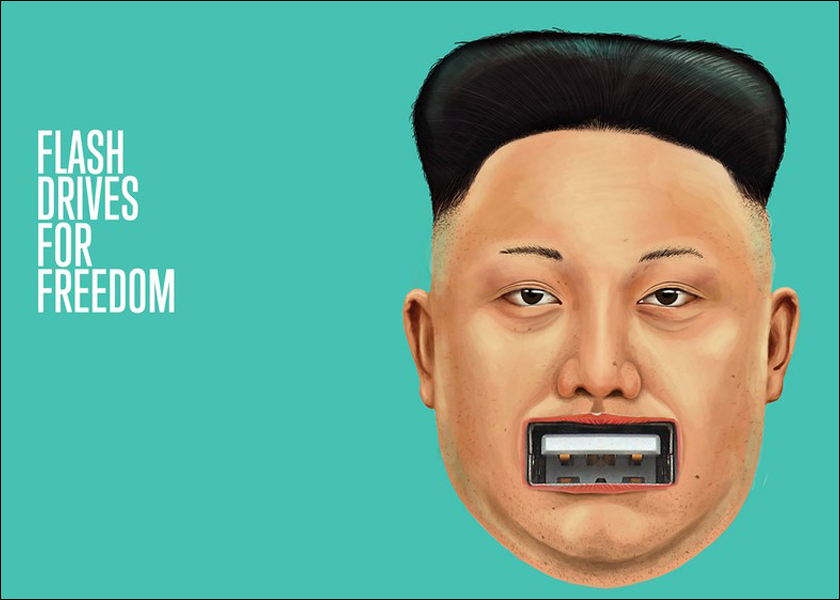

Since its founding, much of HRF’s efforts have gone into “exposing” human rights violations in North Korea and smuggling information into the country (“Flash Drives for Freedom“). It’s also a sworn enemy of China; through its “CCP Disruption Initiative,” HRF “endeavors to increase awareness about the CCP’s ongoing attacks on civil liberties and inspire a change in public attitudes toward Xi Jinping’s authoritarian regime.” As Blumenthal has rightly observed, HRF “functions as a de facto publicity shop for U.S.-backed anti-government activists in countries targeted by Washington for regime change.”

Halvorssen’s extreme-right allies in South Korea

Halvorssen and his organization claim to be non-partisan. But, like Gordon Chang, another fanatical critic of North Korea, Halversson has formed close relationships with the far-right in South Korea and directly intervened in that country’s affairs by vehemently attacking progressives, both South Korean and American, who prefer diplomatic negotiations to war with North Korea. (With respect to activities of this film’s sponsors, it is also important to note that Adrian Hong, one of the founders of LINK, which helped produce the film, was the leader in 2019 of a botched attempt by armed vigilantes to seize the North Korean Embassy in Madrid and kick off a rebellion against leader Jong Un Kim).

Halvorssen’s twisted politics of red-baiting were on full view in 2015, when the Korean peace activist Christine Ahn joined with Gloria Steinem, Ann Wright, Medea Benjamin, two winners of the Nobel Peace Prize, and over a dozen other women from around the world to walk across the DMZ in an attempt to jump-start peace talks between North and South Korea. “The women became, willingly or unwillingly, shills for North Korea’s dictatorship,” Halverrson wrote in a misogynistic attack in the liberal webzine Foreign Policy (Deann Borshay Liem, one of the signers of the PBS letter, directed Crossings, a film about the 2015 march, which I covered for Politico).

Halvorssen and his sleuths apparently scour the world for anyone who engages with North Koreans. One of his targets is the Uruek Symphony Orchestra in New York, which holds annual concerts where American and North Korean music is played. It is one of the only venues where Americans can mingle freely with North Korean diplomats at the UN. (He has also attacked me for criticizing U.S. policy in South Korea over the issue of Gwangju and U.S. military bases. In one post on Twitter, he claimed that I purposely ignore North Korea as the “cruelest dictatorship;” after I attempted to open a dialogue about the DPRK, he kept up the vitriol, so I blocked him).

In his activities in South Korea, Halvorssen works closely with Sang-hak Park, a controversial “defector-activist” who uses funds from HRF and other U.S. organizations to send his propaganda balloons across the border into North Korea. His actions with Halvorssen have attracted enormous attention in NK News and other media sites that sympathize with defectors as well as the foreign press, including Voice of America and The Hollywood Reporter.

These balloon launches have deeply angered Koreans who live in close proximity to the launch sites, which are near the southwestern side of the DMZ border; it has also been criticized by the Gyeonggi Province government, which encompasses the western DMZ area of South Korea.

The situation became untenable for local and national governments in 2017, when South Korea’s President Jae-in Moon was engaged in delicate negotiations with North Korea that led to a brief, two-year period of peace between South and North.

“The brazen attempts by some defectors to disseminate propaganda leaflets in North Korea makes a mockery of South Korea’s laws and creates anxiety for people living on the border,” Gyeonggi’s vice-governor said at the time. “Gyeonggi Province will fully cooperate with the police and with cities and counties on the border and will apply all provincial resources to fully block all illegal distribution of propaganda leaflets.” In response to Park and Halversson’s actions, the Moon government, backed by the National Assembly, passed a law restricting the actions.

Moon’s actions drew a swift response from Halvorssen and other U.S. groups and individuals who support Park and his band of defectors. “The South Korean government’s investigation of Sang-hak Park, head of the Coalition for a Free North Korea, over the distribution of anti-North Korea leaflets is a turning point in history,” Halversson told the right-wing Chosun Ilbo, Seoul’s largest daily, in 2020. “It’s a scandalous act.”

The Venezuelan also launched a public attack on President Moon for pushing the legislation limiting the launch of his balloons (so did CSIS, the former ideological home of Beyond Utopia producer Sue Mi Terry). “This is a tragedy of catastrophic proportions for the North Korean people,” Halvorssen declared in a press release. “Defectors are the only people capable of representing the voices of the 25 million North Koreans living without access to the Internet, without access to outside mail, or to any uncensored information.” He called the bill “a shameful attempt by the Republic of Korea’s government to discriminate against [defectors’] fundamental rights and treat the refugee community like second-class citizens.”

As in so many of his diatribes, Halversson seems to forget he is not a Korean citizen. And ironically, the law he and CSIS denounced so strenuously has remained on the books under the right-wing government of current President Suk Yeol Yoon (Halversson met last October with Yoon’s Unification Minister to discuss human rights in North Korea).

Halvorssen’s arrogance seems to have rubbed off on Park, his ally in the balloon launches and also a member of the HRF board. Park has come under scrutiny in Korea, including from NK News, which is usually quite friendly to the defector community in South Korea.

“Numerous accounts from fellow defector-activists,” NK News reported in 2020, “paint a picture of a provocateur whose sloganeering and brash methods have alienated even his partners. The interviews also offer a glimpse into a grassroots activism community mired by questionable incentives and misappropriation of finances — and a culture where winning foreign grants has become an end unto itself.”

“Park’s approach has also made him something of an enfant terrible in South Korea, even in the close-knit world of North Korea human rights activism,” the article went on. “At his launch sites in villages near the North Korean border, he has scuffled with local residents, who oppose his work for fear that the balloons put a target above their heads. When faced with this sort of resistance, Park has been known to fly into a rage, accusing anyone who stands in his way of being a communist.”

The CIA officer

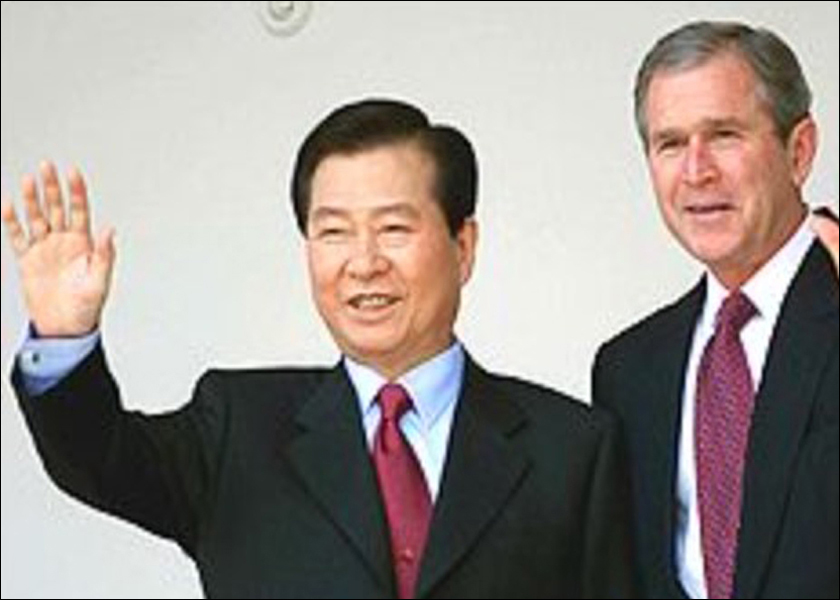

The Beyond Utopia co-producer who is getting the most attention in the media is Sue Mi Terry. She was the director of the Asia Program at the U.S. government’s Wilson Center in Washington from 2021 to 2023. Before she joined CSIS as a senior analyst, she spent seven years (2001 to 2008) at the Central Intelligence Agency, where she “produced hundreds of intelligence assessments — including a record number of contributions to the President’s Daily Brief, the intelligence community’s most prestigious product,” according to the Wilson bio. From 2008 to 2009 she was a director for Korea and Japan at the National Security Council, and from 2008 to 2009 she was the deputy national intelligence officer for East Asia at the National Intelligence Council.

Terry’s experience as one of Bush’s top intelligence advisers on North Korea is significant. It was during these years that North Korea exploded its first atomic bomb, sparking the “nuclear crisis” that continues today.

That test occurred in 2006, five years after Bush rejected the idea of negotiating with the Kim government. Bush did that at the urging of the CIA in the wake of President Clinton’s Agreed Framework with Jong Il Kim that halted North Korea’s nuclear fission program for eight years and almost led to a broad agreement with Pyongyang to halt its missiles sales (see my detailed 2017 article on this agreement in The Nation). After leaving the CIA, Terry took her expertise — and her opposition to engagement — to CSIS, where she honed a reputation as a hard-liner, becoming a favorite in the media.

Her disdain for North Korea was on display in 2013, when tensions escalated between the Obama administration and Pyongyang just before the fiasco about the film The Interview. In an interview with Spencer Ackerman in the neocon-techie magazine Wired, Terry, described by Ackerman as “one of the CIA’s former top Pyongyang analysts,” predicted that “North Korea will launch an attack” that will be “something sneaky and creative,” and warned that an “all-out war with South Korea would spell the end of the North Korean regime.”

No attack ever came, of course. Ackerman is now the national security correspondent for The Nation; I hope his reporting on the next inevitable crisis with the DPRK is better researched than his work at Wired).

In response to the 2006 crisis, the actions of Bush and his advisors were catastrophic. Stephen Costello, a Washington-based consultant who has worked closely with progressive movements in South Korea, told me recently. “The Bush group’s ideological fanaticism not only provoked and enabled the creation of the North’s nuclear and missile capabilities, it also eliminated the leverage that could have improved human rights in North Korea.”

That could be said of Terry as well. She has become a big supporter of the Biden administration’s tough approach to North Korea, particularly its formation of a trilateral military alliance with South Korea and Japan that has drawn sharp criticism from the North and raised military tensions in Korea to their highest levels in years.

Talking to the Washington Post with the fanatical neocon Max Boot, Terry heaped praise on South Korean President Yoon as a “profile in courage” and blasted his predecessor President Moon for “scuttling” an earlier agreement with Japan that was repudiated by South Korea. Yoon, who has condemned Moon and his party for their engagement policies with North Korea, is now one of the most unpopular leaders in South Korea’s history.

Lately, Terry has turned her attention to more profitable opportunities than writing opinion pieces. Her LinkedIn profile lists her as “the founder of Peninsula Strategies Inc., an advisory firm specializing in Korean issues with both government and corporate clients, and a senior advisor to Macro Advisory Partners, a global advisory firm.”

Peninsula Strategies Inc. does not appear to have a website, but Macro Advisory does. It looks like a typical intelligence contractor led by former high-ranking national security officials and think tank executives “who will help you interpret the geopolitical and economic forces impacting your business and develop strategies to navigate them.” Terry is listed as a senior adviser who “advises clients on Korea.” It is well-connected; from 2017 to 2020, Macro Advisory was the corporate home for Jake Sullivan, President Biden’s national security advisor. During his time there, Sullivan earned $37 million a year, according to The American Prospect.

With producers like Halvorssen and Terry involved, it’s impossible to see Beyond Utopia as anything more than a propaganda exercise. At the very least, the media and the Hollywood elite reviewing the film should be asking tough questions of its director and producers about their intent. Moreover, a film documentary should provide the full truth about its subject, not a distorted vision reflecting the beliefs of its producers and funders. That, too, is the prime concern of Liem and the other Asian American directors.

The open letter to the film’s executive producer Lois Vossen at Independent Lens asks her to “add a disclaimer on the film and on the website that indicates the film represents only one perspective of what is a highly-controversial situation and its causes, and offer additional resources for your viewers.” The letter also challenged Independent Lens to “pursue alternative, diverse programming for audiences seeking further information about the issues raised by this film.”

In particular, the Asian American filmmakers wrote, alternative programming should include the voices of Asian Americans, particularly Koreans, “who have a critical understanding of this history and who have been researching, writing about, and grappling with issues of displacement, war, peace, and the impact of U.S. policies on the Korean peninsula.”

Responding to the letter, Vossen and the film’s director wrote that “our goal was to provide only enough background information to ground the personal journeys of our participants, and this historical information was thoroughly vetted by numerous experts and scholars for accuracy and fairness; We are not aware of a single factual error.” But that claim does not stand up to scrutiny.

(related sidebar feature below)

Brainwashing can go two ways: A point-by-point refutation of the documentary Beyond Utopia’s version of Korean history

Beyond Utopia provides a history of North and South Korea that corresponds with the views of the South Korean right and military think tanks in Washington, and is cleverly designed to undermine the legitimacy of the North Korean state founded in 1948.

As a result, Madeleine Gavin, the director who narrates parts of the film, comes off sounding much like the flamboyant defector Yeonmi Park, who often paints a picture of the North that is so fantastic that even the Washington Posthas come to doubt her version of events.

Here is Gavin, as summarized by Deadline:

North Korea. You r house is on fire. What do you try to rescue first? Your kids? Your pet? No, the first thing you reach for is the portrait of the Dear Leader, Kim Jong-un and his father and grandfather that is hanging on your wall, as mandated by the authoritarian government. Everything else can wait. Such is the bizarre and grim reality of North Korea that emerges in Beyond Utopia… Despite the North Korean regime’s attempts to brainwash the populace into believing they live in an earthly paradise, over a period of years hundreds of thousands of people have risked death to try to escape.

But “brainwashing” can go two ways. As the popularity of Yeonmi Park attests, Americans are willing to believe almost anything about North Korea. That is the result of the nation being subjected to disinformation and propaganda from the U.S. government and the guardians of empire about the country for many years.

Here is a point-by-point refutation of the false picture of North Korea’s history promoted by Gavin in this film, which she claims to have found through reading “everything she could get her hands on” on the internet about North Korea “in every language [and] every country.” Well, not everything, as we can see below.

Film version:

In 1910 the expanding Japanese empire colonized what was then a unified Korea. It was a very brutal colonization. Over the next 35 years the Korean culture and the Korean language were nearly eradicated. At the end of World War II when Japan surrendered, they lost the empire that they had been building. Part of the settlement deal was that Korea was split.

Fact:

In 1905, in the wake of a war over Korea between Japan and Russia, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt negotiated a peace treaty that included a secret protocol in which the U.S. approved Japanese control over Korea in return for Japanese recognition of America’s colonization of the Philippines (this egregious act is even taught in South Korean schools). Five years later, with U.S. approval, Japan formally colonized Korea (and yes, it was extremely brutal). Over the next 35 years, Japan created a colonial administration staffed in part by Korean collaborators with security provided by Koreans invited to join the Japanese military and constabulary. As Gavin carefully avoids mentioning, these collaborators, who helped the Japanese Army chase down Korean independence fighters in Manchuria and elsewhere, became the core of the South Korean military and police force created by the U.S. after 1945.

Moreover, contrary to Gavin’s claim, there was no “settlement deal” between Japan and the U.S. after World War II. Instead, Japan surrendered unconditionally in the wake of the Nagasaki bomb, and the U.S. decided unilaterally to divide Japan’s colony at the 38th parallel and then directed Japan to surrender its military forces in Korea to the Soviet Red Army in the north and to the U.S. military in the south.

Stalin, whose troops had entered Korea days before (as discussed with Truman at Potsdam), agreed to this arrangement after the fact. Some units of the Red Army had already crossed into the southern zone at that point. Those units withdrew to positions north of the 38th parallel and to Pyongyang. The U.S. military finally arrived in Seoul, Korea’s traditional capital, on September 8, 1945. As Liem and her fellow directors wrote, “By inferring that the division of Korea was a term of Japan’s surrender, which it was not, [Gavin’s] language erases the role of the U.S. in dividing Korea.”

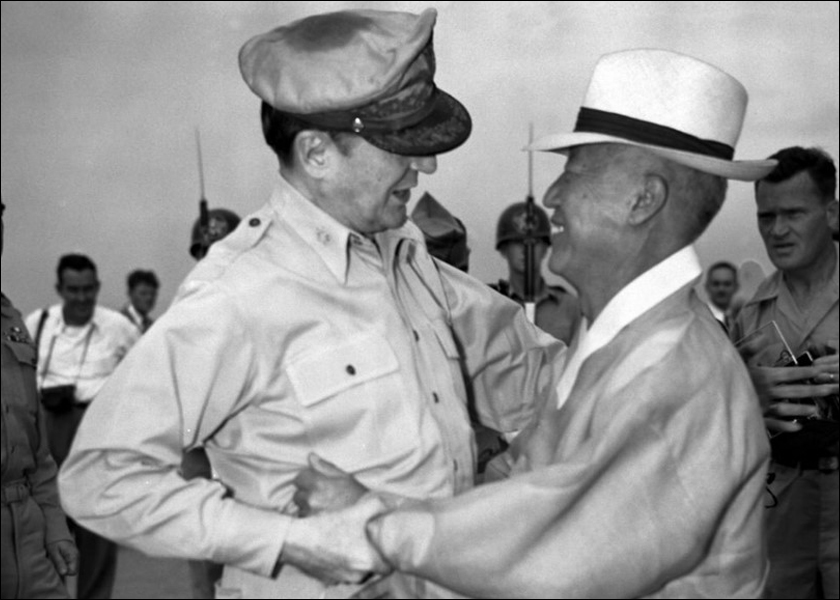

Film version:

The idea was that Korea would shortly come back together and then have control over their own country. In the meantime, the south held a public election and U.S.-educated Syngman Rhee became the first president of what would become South Korea

Fact:

The plan for Korea was spelled out by President Franklin Roosevelt and his British and Chinese allies at their famous conference in 1943 and ratified by Stalin and Truman at Potsdam in 1945. “The idea” was for the allied powers to occupy the Korean peninsula until “in due course” it could be granted independence (Roosevelt “felt the trusteeship might last from 20 to 30 years,” the State Department summary of Potsdam states, while “Marshal Stalin said the shorter the trusteeship period the better.”)

But this did not sit well with the people of Korea. In the days after Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945, Koreans throughout the peninsula declared a People’s Republic and established what were called “People’s Committees” in every province. These committees, north and south, included communists who had led the fierce resistance to Japanese colonialism as well as Christians and nationalists who wanted a united, independent Korea to emerge.

In the initial stage of their occupation, the Soviets recognized these committees as legitimate, and they became the core of the North Korea government the Red Army set up in Pyongyang. But U.S. leaders did not recognize the People’s Committees.

Upon arriving in Korea, the U.S. military set up a U.S. Army Military Government (known as USAMGIK) and, believing the committees were communist fronts, outlawed the formation of a People’s Republic. It then brought in Syngman Rhee, a Princeton-educated Christian who for decades had been an advocate in the U.S. for Korean independence. Rhee was tapped to run the new administrative state for USAMGIK. Rhee hated Japan but reviled communists even more. He built a government of wealthy landlords, right-wing political figures, and former bureaucrats who had collaborated with Japanese colonial rule.

Rhee’s election by a right-wing National Assembly took place in 1948 during a time of severe repression in the South. By 1946, many South Koreans were in open revolt against USAMGIK’s policies and Rhee’s rightist policies. In response, the U.S. and its Japanese-trained military forces launched a vicious counterinsurgency. This secret war fractured the country along ideological lines. According to a U.S. diplomat in Seoul, over 100,000 South Korean dissidents were killed long before the North Korean invasion of June 1950, many of them at the hands of Japanese-trained, Korean military, police, and anticommunist death squads. The counterinsurgency culminated in a brutal, US-directed assault on the island of Jeju, the only province to vote against a U.S.-designed plan to keep Korea divided.

Film version:

In the north, Stalin decided to look for a Soviet sympathizer as a temporary leader in what would become North Korea. And this is where Kim Il Sung comes in… When he was just eight years old, his family moved to Manchuria. Kim Il Sung joined the communist party in China and he eventually fought with the Soviet Union throughout World War II. Stalin heard about Kim Il Sung because of his reputation as a leader of several anti-Japanese guerilla groups. When Stalin brought him to Pyongyang, Kim Il Sung didn’t even speak good Korean… [He] had the dream of reunifying the Koreas under communism. Expanding upon his guerilla contacts, he put together an army and eventually got the support of both Stalin and Mao.

Fact:

Stalin didn’t have to “look for” Il Sung Kim. The guerrilla fighter was widely known as a leader of the anti-Japanese resistance in Manchuria by the Japanese, which (under the future LDP Prime Minister of Japan, Nobusuke Kishi) sent units to hunt him down. As Bruce Cumings, the eminent historian of the Korean War, wrote in his famous two-volume history of the war’s origins, “Kim Il Sung was by no means a handpicked Soviet puppet, but maneuvered politically first to establish his leadership, then to isolate and best the communists who had remained in Korea during the colonial period, then to ally with Soviet-aligned Koreans for a time, then to create a powerful army under his own leadership (in February 1948) that melded Koreans who had fought together in Manchuria and China proper with those who remained at home.”

As Cumings wrote in an incisive article on Kim’s legacy in 2017, his legitimacy as a leader is well established. “The story of Kim Il-Sung’s resistance against the Japanese is surrounded by legend and exaggeration in the North, and general denial in the South. But he was recognizably a hero: He fought for decades in the harshest winter environment imaginable… Koreans made up the vast majority of guerrillas in Manchukuo [the Japanese colony in Manchuria], even though many of them were commanded by Chinese officers… Other Korean guerrillas led detachments too… and when they returned to Pyongyang in 1945 they formed the core of the new regime.”

In other words, these were not just innocuous “guerrilla contacts,” but the leaders of the resistance to Japan. And it was in that capacity as part of collective leadership that Kim got the support of Stalin and Mao to invade the South in June 1950 to dislodge the U.S.-backed Rhee regime, which he claimed did not represent the interests of most Koreans at the time. The rest is history, and the terrible war ended in an uneasy armistice in 1953 that Syngman Rhee refused to sign. No peace treaty was ever signed, leaving the two Koreas in a technical state of war today.

Visit journalist Tim Shorrock’s patreon page to read more and to support his investigative reporting work.