Historian Bruce Cumings reviews strategic failures of U.S. in forging peace with the North | By Martha Vickery (Summer 2020 issue)

Could the first modern forever war also be the last to be formally ended?

A coalition of peace organizations working for a Korean War peace treaty with North Korea teamed up to invite historian Bruce Cumings to talk in a public Zoom/Facebook Live meeting about his insights into the meaning of this anniversary in a historical sense and a human sense, to be commemorating a war that was halted, yet never formally ended. An audience of 500 signed up for the webinar, entitled Korea: The Unknown War.

June 25 came and went in U.S. society quietly this year, but it was recognized with several virtual events by Koreans because it was the 70th anniversary of the start of the Korean War. It is also notable as a war which has never been formally ended with a peace agreement. In the community of Korean Americans working for peace and reconciliation, there were several commemorative events for storytelling and learning about the history of the war and prospects for peace in the future.

In introducing Cumings, Jong Dae Kim, representing the co-sponsoring organization Re’Generation Movement, recognized Cumings’ personal contribution to his family and the democracy movement in Korea. Kim is the grandson of Dae Jung Kim, the former president of South Korea (1998-2003). Dae Jung Kim was later conferred the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to broker a peace deal with North Korea, and for easing relations between the two Koreas.

In the early ‘80s, Jong Dae Kim said, his grandfather was exiled to the U.S. for leading the democracy movement during the Do-Hwan Chun military dictatorship of the early ‘80s. When his grandfather made the risky decision to return to South Korea on his own, “a group of Americans volunteered to accompany my grandfather for his return to South Korea to protect him and act as human barricades. Dr. Bruce Cumings was one of them. So, Dr. Cumings, I am deeply grateful for you standing alongside by grandfather and also for standing alongside South Koreans as they fought for democracy.”

Recalling that time in his life, Cumings, former chair of the History Department at the University of Chicago, and author of several books on the Korean War, said it was 1973 when he and Dae Jung Kim met. Cumings was lecturing in history, and invited the young democracy leader to speak to his class. Later on, in a government indictment of Dae Jung Kim “they brought up remarks that he made in my classroom, and there were only about eight students in the class.” There was apparently a spy planted in the classroom.

“That was the kind of threat your grandfather dealt with,” Cumings said. “He was always under threat from the militarist government.”

Kim also introduced the discussion moderator, Catherine Kilough. Kilough is the advocacy and leadership coordinator of Women Cross DMZ, which cosponsored the event. As a fellow of the Ploughshares Fund, Kilough helped build and manage an advocacy coalition in support of U.S.-North Korea diplomacy. She also writes about issues of U.S. Korea relations as a commentator for major media.

As early as July 2019, then-presidential hopeful Sen. Joe Biden made campaign promises that as president, he would end all the “forever wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East” and terminate U.S. involvement in the Yemen civil war. In February, Edward Wong, writing in the New York Times (Americans demand a rethinking of the ‘forever war’) discussed the opposition to Trump’s implied willingness to perpetuate another “forever war” in the January drone strike killing of Iran’s Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani.

In this case, the “forever war” the writer referred to is the 18-year-old War on Terror, begun in 2001 when the terrorist group Al-Qaida killed 3,000 people and destroyed New York’s World Trade Center and part of the Pentagon building in Washington, using hijacked passenger airplanes. “The premise is that aggressive intervention abroad, forward deployments and fighting perceived enemies “over there” keep the United States safe,” Wong wrote.

Critical attention has, since then, been focused on Trump administration offensive attacks on implied enemies abroad, however, Cumings told the online audience of peace activists and supporters that this concern does not seem to extend to the unended Korean War. The idea of a “forever war” is not new. “The original ‘forever war’ is the war in Korea,” Cumings pointed out. “Even though the peace has generally been held by armistice since 1953, the war is not over and it could resume almost at any time.”

It is “very typical,” Cumings said, for people to believe the Korean War began June 25, 1950. However, that date was chosen because it is the date North Korea invaded South Korea. Prior to that, he explained, the U.S. had troops on the ground in South Korea, and a military government there, for five years. The Korean War was also exacerbated due to American military action in advance of a war. There was fighting across the borders by South and North beginning in 1945. This anniversary of the war is “75 years, not 70,” he said.

Although Roosevelt wanted South Korea to be governed through a trusteeship until it could raise its own leadership, Cumings said. “The State Department …felt the only way they could do that was with the military occupation.” Roosevelt died in February 1945, and the idea of a trusteeship was abandoned.

Because the guerilla fighters for Korean independence had fought so hard in Manchuria against the Japanese, the State Department thought the estimated force of 30,000 guerillas “would come back from World War II and easily take over Korea,” Cumings said. The most famous of these was Il Sung Kim, who would be installed as the first leader of the new North Korea.”

“During World War II, we went in [to Korea] trying to block Kim Il Sung, and we are still trying to block his grandson Kim Jong Un. Only he’s got nuke weapons and intercontinental missiles,” Cumings observed. “So, this is just a colossal strategic failure when it comes to American policy toward North Korea. It shows us how easy it is to get into a war. It happened overnight, when the U.S. intervened in 1950. And how desperately hard it is to get out of that war.”

So far, the U.S. government has taken the tactic of squeezing North Korea into submission on nuclear arms control with embargoes and sanctions, Cumings said. “Probably, North Korea is the most sanctioned country in the world right now. Certainly, it is the most sanctioned country over the last 71 years. And I don’t know if any positive result that has come from that.”

Instead of peace first, followed by negotiation, the U.S. has generally demanded surrender first, which would be followed by negotiation. However, North Korea has been persistently defiant over many years of the same or similar tactics. The Barack Obama regime’s “strategic patience” intiative kept U.S.-North Korea relations at a status quo, with no progress.

The U.S. has not been very successful in its prosecution of “forever wars,” Cumings said. “There have been five major wars since 1945, and we only won one of them; that was the Persian Gulf War in 1991. In many ways, that was a Pyrrhic victory, because the W. Bush administration decided to continue that war by trying to achieve regime change in Iraq.” Forever wars still unresolved include “a stalemate in Korea, a defeat in Vietnam, a probable defeat in Afghanistan …the Taliban are stronger now than when we invaded Afghanistan, and the civil wars in Iraq are still are not solved.

In all these cases, the clash was political, and in Korea and Vietnam, the U.S. greatly underestimated the force of nationalism and anti-colonialism in countries that had been occupied, Cumings said. Many years have gone by since the end of the Korean War. North Koreans are “laser-focused” on the war history. They have never settled the war outcome with South Korea, the U.S., or Japan, and none of the countries have moved on from the armistice to something better.

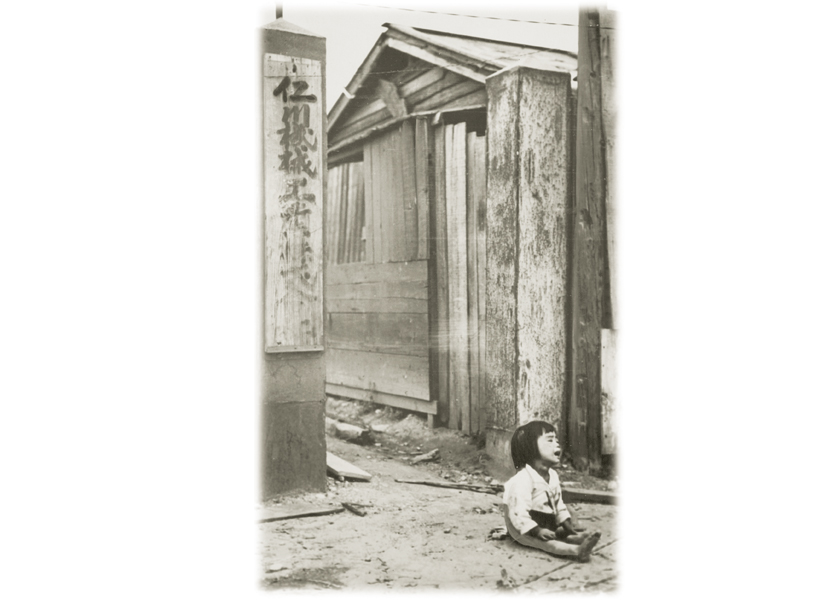

Cumings mentioned Su-kyoung Hwang’s recent history account Korea’s Grievous War, which looks at the wholesale slaughter of civilians during and before the war. “When you read that book, you realize that the Korean War was one of the most violent wars in history. Not just soldiers facing up to each other and dying, but hundreds of thousands of civilians who were killed in political massacres, primarily by the south, either by government or right-wing youth groups.” There were also massacres on Jeju Island of civilians suspected of being communists. In the end, the violence took 10 percent of the lives on Jeju Island.

Reading about the massacres of civilians in the south during that era in the Hwang account and others, Cumings said, he realized that, “I think there was no way the North Koreans were ever going to allow all of this to go on in the south, as their leftist friends were slaughtered. …So the war was probably inevitable.”

Kilough, in introducing the Q and A session, said U.S. policy has been principally concerned with North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, which began in the 1990s, but many U.S. lawmakers are reluctant to acknowledge that the U.S. introduced nuclear weapons to the Korean peninsula in 1958, “an obvious violation of the Armistice Agreement, even the State Department legal advisor at the time cautioned against doing so for that very reason.” The U.S. has since removed its nuclear weapons from South Korea, but it still maintains nuclear weapons in the region, and South Korea is under the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Kilough asked how this U.S. history has informed North Korea’s nuclear policy today

Cumings said he has read the now-public original records from 1957 of the UN Security Council, when U.S. leadership was warned against violating the Armistice, “but they basically decided ‘oh, what the hell, let’s do it anyway,’” Cumings said. The U.S. military thought about a strategy of using small nuclear weapons if North Korea ever started a new war, he said. Developing nuclear weapons was the logical and only way to deter the U.S. from using its weapons against North Korea, Cumings remarked. The only surprising part was how long it took North Korea to do it.

It is very poorly understood, Cumings said, that the Korean War is primarily responsible for the national security situation we find today, with permanent military bases in 150 countries (more than 900 bases total), with a huge standing army that had never been established before the war. Today, tens of thousands of U.S. troops are in Japan, South Korea and Germany. “Nobody ever talks about this, and it is hidden in plain sight.” The Korean War caused the defense budget to quadruple, and it never went back to former levels, he said. “That’s the world we still live in.”

In recent months, North Korea has blown up the South-North diplomatic liaison office and destroyed sites that were established in and around the Demilitarized Zone by both Koreas in a clear signal of its frustration with the abandonment of peace initiatives by South Korea, Kilough noted. “South Korea has not been able to move forward on large cooperative projects, largely because of the U.S. sanctions regime and the Maximum Pressure campaign.” People are worried about renewed fears of a new war, she said.

Cumings said he thinks the strategy is chiefly aimed at making Trump pay attention. “But I don’t think Donald Trump is paying attention to anything but trying to get reelected, and I don’t expect anything to happen between the U.S. and North Korea until we get a new president.”

Since the Hanoi meeting between Jong Un Kim and Trump, which ended prematurely with Trump leaving the negotiating table on February 28, 2019, there have been no further attempts by the Trump administration to discuss a peaceful resolution to the war.

Despite the failure of the parties of the Korean War to forge peace, Cumings said there is hope in South Korea under President Jae-in Moon. “I have been heartened by his policies towards the north and his many, many attempts to get the U.S. to do something to break the logjam in Korea, to end the war, to reestablish ties.” Although Donald Trump seems to have distanced himself from the issue of making peace with North Korea, “There’s much that could be done, and Moon still has two years in power.”

This is different than the previous administration of South Korean President Geun-hye Park, who maintained a hard-line policy against the North. Where Obama had no willing South Korean government leaders to work with, a future Joe Biden administration, which has pledged to end America’s forever wars, may arguably have a better chance.

In addition to the Re’Generation movement, which mobilizes immigrant young adults to be active peacebuilders in U.S. society, co-sponsors included: The global women’s coalition Korean Peace Now Grassroots Network, and its U.S. founding organization Women Cross DMZ; and Peace Treaty Now!, a network of 40-plus Korean American organizations committed to a formal end to the Korean War.

This and other webinars can be viewed on the Women Cross DMZ website: womencrossdmz.org