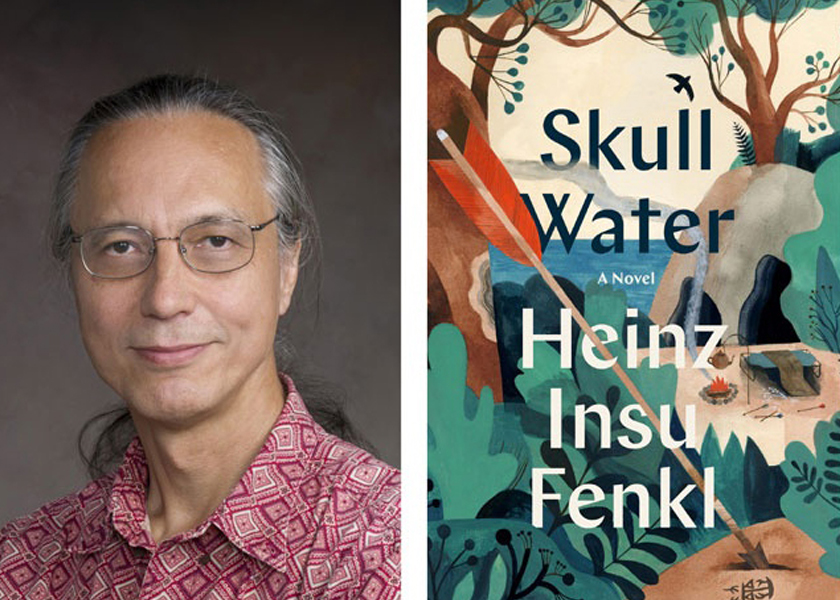

In Skull Water, Heinz Insu Fenkl weaves a hero’s quest into an insider’s story of 1970s Korea | By Martha Vickery (Winter 2023)

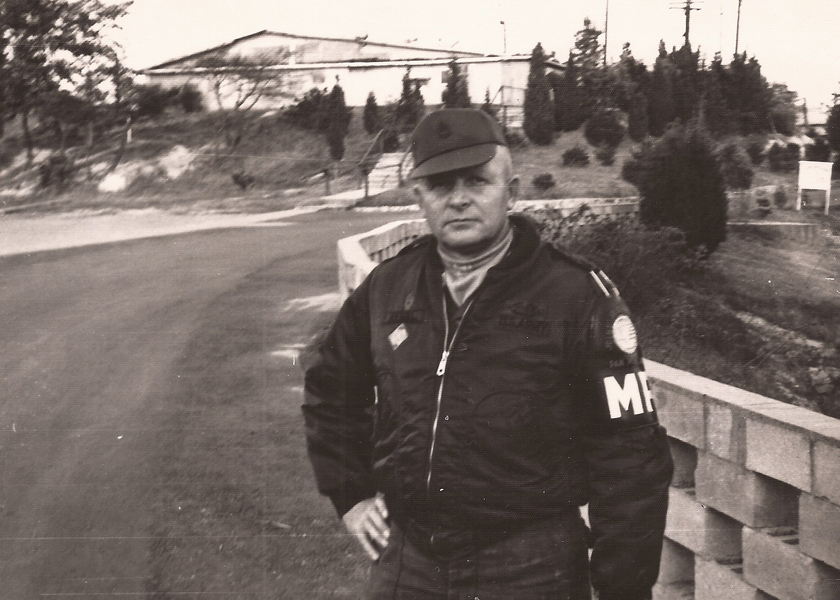

As a kid growing up near a U.S. Army base in Korea, son of a Korean mother and a German soldier father, Heinz Insu Fenkl ran with a small gang of half-Korean military kids who belonged nowhere and everywhere.

In February, the author, scholar, and professor of English at the State University of New York at New Paltz launched Skull Water, his second autobiographical novel based on his gritty, often perilous youth in the early ‘70s in Seoul, and near the huge ASCOM base in the Inchon area. Back then, the country had a thin veneer of rapidly-changing modern life, but just under the surface were the unchanging ways of traditional Korean seasons, stories and spirituality.

His first novel, Memories of My Ghost Brother, tells the story of Insu as a younger boy; Skull Water is a kind of a sequel, the life of an adolescent just before his jump into the unknown – relocation to yet another military base, this one in California.

Both novels read more like memoirs, and when talking about some of the incidents in Skull Water, Fenkl often adds “and this really happened.” As fiction, the author had more freedom, with ordering parts of the story, changing the timing, and in being able to leave things out. In some cases, he said, the truth really was stranger than fiction, so he modified his telling to make it more believable.

Fenkl’s story of growing up describes two disparate cultures he inhabited. His daily life was tied to the U.S. military base, but at his mother’s house outside the base, he absorbed Korean daily life. There was a tension of ancient and modern – he was especially attuned to ancient beliefs and wisdom absorbed through his Korean elders.

From a broader perspective, the rapid growth and change in Korea during that time mirrors the life of the character Insu. It describes a country trying to rebuild within 20 years of the unspeakable losses of the Korean War, with the nation under military dictatorship.

A significant character is Big Uncle, his mother’s eldest brother. Intelligent and well-read, Big Uncle rejected the eldest son’s traditional role of administering the family estate. Instead, after the war and many misadventures, he lives in exile in a mountain cave, across the river from his village. Big Uncle is a geomancer, a traditional vocation that involves reading the energy (ki in Korean) of the landscape and finding the best places for important sites such as graves, houses, and well water. For many years he treats a mysterious foot injury that never heals.

Big Uncle also divines the future by throwing tiles to form the hexagrams of the Chinese I-Ching (in English, the Book of Changes), a ceremony that would have a deep influence on Insu the character, and on Fenkl as an author writing Skull Water many years later. Rejected by most of his family, Big Uncle welcomes the friendship of the young Insu.

The title Skull Water describes a quest that Insu pursues after he hears that the water remaining in a dead person’s skull after the flesh is gone will cure any illness. His determination that he and his friends will find skull water and cure his uncle is both a heroic journey and a fool’s errand. For Insu, the adversity and the foolishness of the quest is also a journey of self-discovery that enables him to appreciate his loyal friendships and family ties, even as their familiar presence are about to be lost to him.

The narrative about Insu in the 1970s is interspersed with chapters about Big Uncle’s life as he flees southeast ahead of the North Korean army in 1950, hampered with a badly injured foot. It describes how a young woman, also alone, befriends him and provides for him along the way. This part is truly fiction – the author does not know what happened to his uncle on his lonely flight for his life to Busan, only that it must have changed him profoundly.

Fenkl writes with insider knowledge of the squalid life in the camptowns around the U.S. military bases, and the corruption, exploitation, easy money and human misery of those times.

As a multi-lingual scholar of Korean folklore and literature, he also weaves in folktales, Daoist philosophy, Buddhist wisdom, and shamanic rituals into his writing, creating an atmosphere of stark realism mixed with dreams, myths and glimpses of the spirit realm.

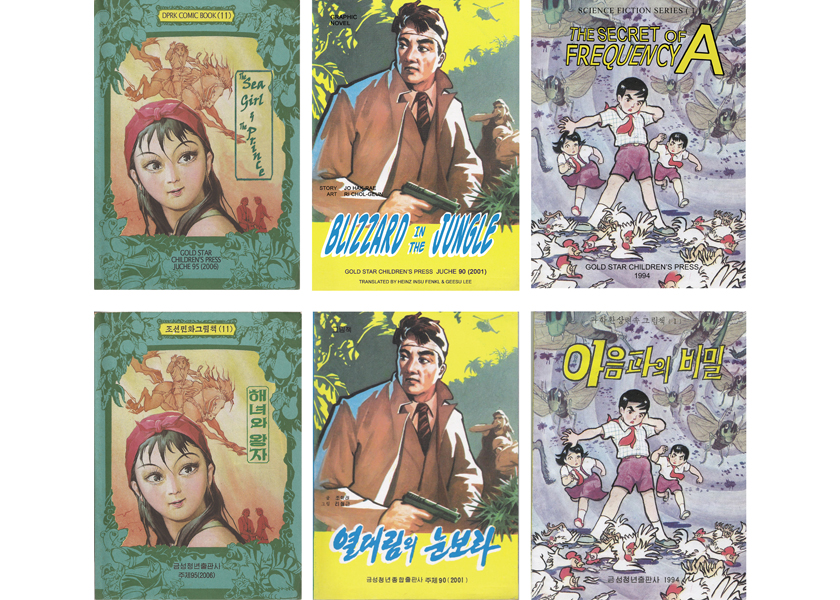

Fenkl’s fondness for folktales also extends to popular culture tales told in Korean comics, graphic novels and films. He voraciously read comics and watched movies as a kid. He has collected and translated Korean comics as an adult, including a several series of North Korean comics for Korean Quarterly, such as The Crystal Key, which was published over several years (and will soon be uploaded to the “webtoons” section of the KQ website). The North Korean cartoons included interpretive notes to enable readers to understand North Korean culture and political concepts through the stories.

In a launch event sponsored by the Korea Society in early February, Fenkl explained how he used the I-Ching (specifically his Big Uncle’s ancient version) to guide and inspire his writing. He illustrates the novel with ancient Chinese pictograms, and explains their layered meanings in one of the afterwords. Readers fluent in Korean and English, who also know some Chinese characters, will find wordplay in the story which layers richer meaning from Korean literature and folklore into the story, the author said.

The character Insu describes is what the author saw many times in his youth; Big Uncle throwing black and white stones six times, one for each line of the hexagram, while muttering the correct interpretive phrases for each one. He assembles the character’s six lines by drawing each line in the dirt, then interpreted the meaning of the character.

Fenkl explained how the story is divided into six parts, similar to a shamanic kut or ritual ceremony to prepare a spiritual path for the dead. The story’s unfolding is also kut-like, as Insu goes through a self-discovery process, puts to rest the ghosts of his past, and becomes spiritually ready for an unknown future.

The narrative, from the perspective of a child, describes the dangerous freedom Insu enjoys as a mixed-race kid of a military officer and a Korean black-marketeer mother. With their military transportation passes, his little gang goes everywhere by bus or sometimes in a truck with a soldier who is going that way. They were seldom supervised, and make friends with questionable characters – one soldier who sells black market Army goods, and another who runs the morgue. They visit bars, drug dens, and a dog market. Black-market sellers, including Insu’s mother and his friends’ mothers, were prevalent in the neighborhood because the nearby Camp Market base was a major U.S. military supply hub for the entire country.

The author remembers many misadventures with his band of camptown kids, which he relates now with a mix of humor and horror. After a hospital burned down “we found medical supplies still in there, so we would take those supplies and sell them on the black market in Shinchon,” he said, “or the other thing we would do is crawl into the dumpster outside the dispensary … In those days they did not have those biohazard containers, so we would take the used syringes and clean them and sell them to drugstores.”

He also remembers swimming in a creek with his friends which was actually an open sewer on the ASCOM base perimeter. “We would see human feces floating down,” he said, and then would keep swimming. “We were totally clueless as kids.”

In more recent years, the ASCOM base has had a more sinister reputation, Fenkl said. Former military personnel who lived near ASCOM base sued the U.S. military for alleged poisoning by Agent Orange. The carcinogenic dioxin Agent Orange was used as a defoliant at the DMZ, and was allegedly stored at the ASCOM base. The other base Insu visits, the Yongsan Garrison in Seoul, was vacated by the U.S. government roughly five years ago, and now looks like a vast, empty space rimmed with skyscrapers. There are numerous competing plans for this piece of prime real estate – Fenkl said he favors the option which would develop the land into a park in an area where there are few public green spaces.

Camptowns were also known for sex trafficking and other exploitation. Toward the end of the story, Insu’s older friend Patsy (a former member of the kids’ gang), another mixed-race teenager, is living in a hotel paid for by a Japanese man who is mostly absent. She spends her time dressing up like Holly GoLightly, played by Audrey Hepburn in the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s. The persona is so convincing that passers-by murmur “it’s Audrey” as she goes by.

Patsy, a few years older than Insu, is both a dreamer and a truth-teller. She treats Insu to a room service lunch, and explains that she will soon be marrying – not the Japanese businessman, but another guy, a military officer who went to West Point. When he suggests that it doesn’t sound like much of a plan for the future, she replies that “people like us don’t really have a future. The present just keeps …changing, is all.”

At the end of the story, Patsy sends him a postcard she illustrates with an Audrey Hepburn theme, telling him she has started a new life with the West Pointer. The postcard is a message to Insu that the last of his posse is gone – one boy has already departed for the U.S. with his family, the other mysteriously disappears. Upon receiving the postcard, Insu cries in heartbreak.

Patsy is manipulating circumstances to escape family violence, and using the sexual exploitation she is suffering to help her exit Korea. At his age, Insu does not know what to make of it, but the reader “will probably infer that her future is not going to be that romantic Breakfast at Tiffany’s scenario she seems so fascinated by,” Fenkl said.

The character seems like a dreamer, but in fact her eyes are wide open. On the one hand, the Audrey character is a performance, “but on the other hand, it is her fantasy wish fulfillment which, deep-down, she knows is not going to be how her life plays out,” the author observed.

As Insu meets and gives his last goodbyes toward the end of the story, more than one character explains the aversion military folks have to saying goodbye, both because it’s painful and too frequent in that life; also because there is a good chance of seeing one another at another military base, at some future date.

Interestingly, the author gives away no grown-up clues about any character’s actions in the narrative. Instead, he stays true to the Insu of adolescence, an unreliable narrator who has little insight into adult motivations, and who thinks only vaguely about the future. The reader has more insight than Insu throughout the story.

He had few mentors at that age, the author reflected at his book launch event. He remembers thinking of pursuing a military career like his dad. Instead, as an adult, the author’s life path was something he never could have predicted, one more like what his Big Uncle would have followed, had he lived in more normal times.

Throughout the story, spiritual experiences seem to chase Insu, and teachers like his Big Uncle and one monk, Mumyong sunim (sunim is a form of address for a monk), seem to appear when he needs them. The monk shows up a couple times when Insu is in the mountain forest near the temple. Their final conversation occurs near the end of the story, when the monk finds him at a grave trying to make amends by carrying out a solitary ceremony. Their conversation seems to prepare Insu for the final spiritual reckoning to come.

Mumyong tells Insu of the famous story of Wonhyo the monk, who drinks water from a skull by accident, in the dark while spending a night in a cave. The water is satisfying and delicious. His discovery the next morning that he drank water from a skull horrifies him, but from the experience, he achieves enlightenment. A missing piece of the story, Mumyoung tells Insu, is that a mischievous spirit (tokkaebi) led Wonhyo to drink the skull water. Did the tokkaebi do a good thing while making mischief?

Mumyoung points out that Insu has tried to do the right thing in terms of spiritual amends, but that he is still ignorant, particularly of the consequences that could proceed from his actions. Insu realizes he is lost in his ignorance – he shares his uncertainty with the monk. “Ignorance is ignorance. Knowledge of one’s ignorance – awareness of it – now, that can be a good thing,” Mumyong replies.

Fenkl said that American author Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that the journey of the best boat is one of “a hundred tacks” in a zig-zag course when going against the wind. When you are sailing on a tack “you think that’s where you are going, but when you pause to look back, you realize you have been going northeast the whole time,” Fenkl explained. The advantage of maturity is that one can wholistically see the direction of one’s life, he suggested, by looking back on many tacks; that perspective is denied to the young. “The monk is pointing out that kind of quality,” he said.

Insu is left with some assurance that his future is not so dark as it appears in the moment, but still fears that when he leaves “the land would be pulled out from under us, and if we ever did return, it would not be the same place that had received us,” the author writes.

One of Fenkl’s more challenging projects in recent years was in producing a translation of 108 Zen poems by the monk Musan Cho Oh-hyun. While writing Skull Water, those Buddhist spiritual insights were very much with the author. Fenkl noted that the conversations between Insu and Mumyoung were taken, in part, from conversations he had with Cho. In an afterword, the author reveals that he had a dream conversation with Cho that inspired him to take on the difficult translation project.

It was Asian studies classes starting his second year of college that helped the author to reclaim his Korean side, Fenkl reflected. With the benefit of some academic context, he was able to see his culture of origin in a new light. “In trying to figure out the sort of things my Big Uncle was doing in consulting the I-Ching, I educated myself in my own tradition. “I became a real professor and not a dilettante scholar like Big Uncle, but I learned the I Ching also through his unorthodox method and now use it that way. It’s a parallel in my own life.”

Fenkl was able to write Skull Water in recent years in part because some whose lives are fictionally depicted, like his mother and Big Uncle, are now gone. Those stories could not have been told so easily in the late ‘90s, when he penned Memories of My Ghost Brother.

A part of what allowed the author to weave folklore, shamanism, Buddhism, literature, and daily life into one story was his education and many years of fascination and hard work on literary translations. He conceived the story of Skull Water and began to write it about 25 years ago. During the same years, he also published eight books of Korean literature in translation. It was not really a 25-year project he said. It was intermittent due to the constant flow of other work.

His story-telling may have also emerged from family tradition, along with a dose or two of DNA. In addition to Big Uncle, whose every conversation was a story, Fenkl said his mother was a dream interpreter, and is described in Skull Water doing fortune-telling with hwatu (flower cards, used for gambling games).

One of his mother’s two sisters is still alive in the U.S. Fenkl is hoping, perhaps through FaceTime, to hear more of her life, for a possible future book about her and the lives of his mother and the other sister.

Although it is autobiographical, the story is fiction because it is the easier path. Fenkl can only write his own experience, and guess at the experiences of others. If his Big Uncle could read his book, Fenkl said, “he would probably be very amused, and would want to give me a lot of corrections about the Korean War sections. I would have to write another book for him.” If his mother could read it, he said, “she would argue with me about many of the things I depicted about her, like the gambling losses, and the money she stole from me. And then I would have to write another book about her!”

Heinz Insu Fenkl’s website is: www.heinzinsufenkl.com Skull Water is published by Spiegel & Grau, New York (www.spiegelandgrau.com)