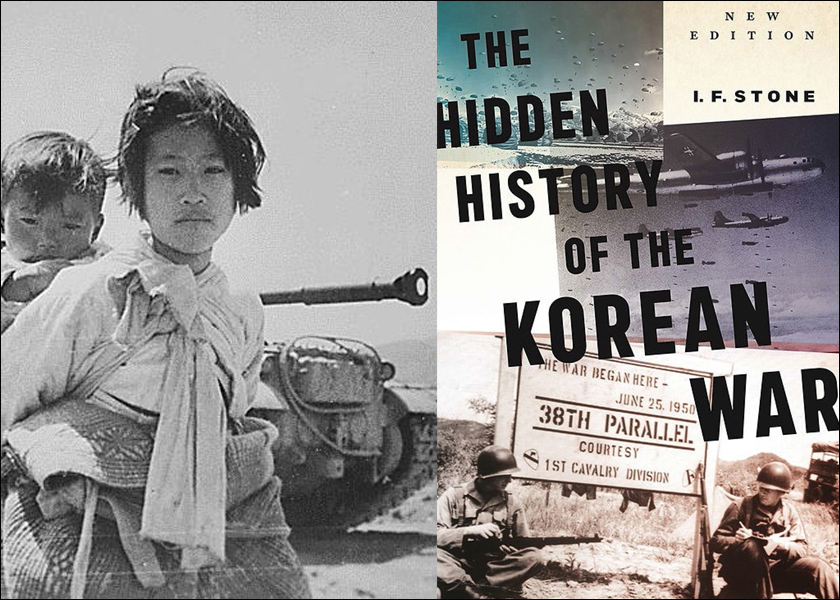

The Hidden History of the Korean War ~ By I. F. Stone

(Monthly Review Press, New York, 2023, ISBN #978-1-6859-0008-3)

Review By Tim Beal and Gregory Elich (Spring 2023)

For a book on contemporary events to have a second edition 70 years after the first is a rare achievement. I.F. (Izzy) Stone’s The Hidden History of the Korean War has a continuing relevance for three major reasons: it is a tour de force of investigative journalism; the Korean War was a pivotal event in post-1945 history; and because this author’s investigation helps us understand what has happened since then, and what may happen in the future.

There is a certain constancy in human affairs. Deceit, deception, and manipulation are characteristics of power, perhaps especially of modern “democratic” political power. What country does not claim to be adhering to democratic principles? In addition, the international framework fixed in place by the Korean War, dubbed the Cold War, is still with us despite some attempts at rapprochement.

In 1952, when Hidden History was first published, the U.S. was in a hot war with North Korea and China, and in a cold war with the Soviet Union. In 2022, when this edition was issued, the U.S. is in proxy war with the Russian Federation, successor to the Soviet Union, and in cold war, perilously close to turning hot, with North Korea and China. In the U.S., the president is struggling to stay afloat in a turmoil for which his administration is partially responsible. The political climate is increasingly intolerant of dissent, redolent of McCarthyism. Stone would find the 2022 situation in sadly and depressingly familiar.

Penetrating deceit and deception: Stone’s investigative journalism

Decades after its initial publication, Hidden History remains as relevant as ever in its analysis of U.S. foreign policy and war-making modes, and in its telling of the hidden history behind the official narrative. Stone believed that he could only be persuasive with a domestic audience if he “utilized material which could not be challenged by those who accept the official American government point of view.” Therefore, Stone limited his sources to official U.S. and UN documents and American and British newspapers. It is interesting to note how much revealing information Stone uncovered through his analysis coupled and investigation. He compared mainstream sources, noting discrepancies, omissions, emphases, and framing. This revealed a complex reality behind official obfuscations. Stone’s analytical method remains a relevant model for analyzing and interpreting official sources.

War on the Korean Peninsula was an opportunity for the U.S. to advance its geopolitical interests and those of key Asian clients. In the popular imagination, the war started as a surprise North Korean attack. However, by closely examining his sources, Stone points to ambiguities that muddy that picture.

The author finds considerable evidence suggesting U.S. and South Korean officials had probable foreknowledge of a planned offensive by North Korean forces, and chose not to prevent it. South Korean President Syngman Rhee had recently suffered a dramatic defeat in Assembly elections, and his political future looked shaky. He was not confident in U.S. support. On the American side, Gen. Douglas MacArthur and many in Washington were eager to launch a global anticommunist crusade, regardless of the cost in lives. A war in Korea was an opportunity for such a crusade.

Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan also dreamed of a wider war, in which he hoped his forces would retake the Chinese mainland. Stone brings up some indications that the war was precipitated by Rhee, possibly in collusion with Chiang Kai-shek. However, he stops short of pursuing this line of analysis. Early reports, later overwhelmed by official propaganda, said that “The South Koreans have attacked North Korea.” Then there was the strange business of the soybean market. Before the war, relatives and associates of Chiang Kai-shek bought soybean futures, which yielded great profit after war broke out. Sen. Joseph McCarthy had also made a felicitous foray into soybeans.

The Korean conflict also boosted President Harry Truman’s “get tough” policy to escalate Cold War tensions. It provided the pretext for quadrupling the U.S. military budget, cemented the American base presence throughout the Asia-Pacific, and set the U.S. on a one-way road to a militarized economy and foreign policy that remain with us to this day.

Stone situates the U.S. role in the Korean War in the context of the global Cold War, in which it can only be fully understood. A central theme is the tension between the Truman administration’s hostile containment policy of “political boycott and economic blockade” of the socialist countries and the anticommunist conservatives in Washington pushing for more aggressive action. The latter group’s hope for a global war against communism was fueled by MacArthur’s desire to steer the U.S. into a full-scale war with China and the Soviet Union. Stone details MacArthur’s machinations in eye-opening and disturbing detail. His is a memorable takedown of an American icon.

MacArthur and Truman were in accord, however, in thwarting every opportunity to bring the war to an early end. Each had his motive to keep the conflict going: MacArthur hoped the war would grow into an international conflagration; Truman wanted to shift the U.S. economy to military Keynsianism to ensure a fervently anticommunist foreign policy.

Civilians in U.S. wars are typically rendered invisible in mainstream media reports. The Korean War was no different in that regard, but Stone wanted to expose this harsh reality. On this subject, he writes with evident compassion. Such empathy seems startling in contrast to the near-total absence of such feelings in American journalism since the end of the Vietnam War.

In one example, Stone examines U.S. Air Force communiques issued after a bombing campaign in September 1950, which complained that there were few targets left because there was little left to destroy. “These communiques should be read by anyone who wants a complete history of the Korean War,” Stone suggests. “They are literally horrifying.” He quotes one document that reported large fires in villages that jets had attacked with rockets, napalm, and machine-gun fire. “Why was not explained,” Stone acidly observes, adding, “A complete indifference to noncombatants was reflected in the way villages were given ‘saturation treatment’ with napalm to dislodge a few soldiers.” Another operational summary stated that an attack on several villages achieved “excellent results” with bombs, rockets, and napalm. Stone lets the words sink in for the reader with his bitter comment, phrased to encourage a pause for reflection: “The results were…‘excellent.’”

Stone found some U.S. Air Force reports deeply disturbing on another level – they expressed delight in death and destruction. “There were some passages about these raids on villages which reflected, not the pity which human feeling called for, but a kind of lighthearted moral imbecility, utterly devoid of imagination — as if the fliers were playing in a bowling alley, with villages for pins.” Among the examples Stone provides is one from a captain who led a flight attack group. His report stated “You can kiss that group of villages good-bye.”

The author believed that journalists generally acted as stenographers, parroting the official narrative and displaying a lack of curiosity about the complex reality on the ground, or that reporters acted as cheerleaders for war or an escalation of violence. Lulls in combat worried MacArthur, who wanted to keep the pressure on Washington to widen the war. By juxtaposing MacArthur’s hyperventilating reports against the situation on the ground, Stone exposes the general’s duplicity in damning detail.

MacArthur knew his image carried weight back home, and that he could count on the media to disseminate the message he wanted to convey. The author agrees that this was true — U.S. newspapers tended to ignore the more sober-minded assessments that officials provided and ran with MacArthur’s wild fear-mongering claims in the headlines. Regardless of the military situation, the newspapers fed the American public a steady diet of MacArthur’s fabrications.

Even after MacArthur was removed from his position, the U.S. remained wary of peace. After the war entered a stalemate, the only reason Washington had to drag out negotiations by continuing the war was to score political points. Quoting U.S. officials to illustrate their uneasiness at the prospect of peace, Stone concludes, “The peace talks were regarded by these leaders as a kind of diabolic plot against rearmament.” The media, not surprisingly, fell in line behind this narrative, and Stone cites saber-rattling editorials from the Washington Post and New York Times.

Stone’s analysis of peace negotiations is a masterpiece of investigative journalism. He unveils how the U.S. intentionally kept the war going long past the point where either side could make any significant gains on the ground. Indeed, when the book was initially published September 1, 1952, another year passed before the armistice was reached. The main sticking point was the refusal of the U.S., in collusion with Syngman Rhee and Chiang Kai-shek, to return prisoners of war to their home countries, according to the Geneva Convention.

Instead, the U.S. was intent on scoring points regarding Chinese and North Korean “legitimacy.” Prisoners held by the U.S. and South Korea were subjected to enormous pressure to reject a return to their homelands, whihc gave a false legitimacy to the bankrupt regimes of Syngman Rhee and Chiang Kai-shek. The protracted wrangling over this issue meant that combat continued past the point of any military rationale.

As Stone thoroughly documents, each time it appeared that an agreement was imminent, the U.S. undermined the talks. Stone offers many examples of how the U.S. extended the time in the war.

In August 1951, when North Korean Gen. Nam II agreed to adjust the truce line from the 38th Parallel what was then the battle line, and it seemed an agreement was close. The U.S. military then launched a heavy artillery barrage into the Kaesong neutral zone, agreed-to by all parties as a place off limits to combat for the duration of the talks.

Other incidents ensued, including when a U.S. warplane strafed a North Korean truce jeep on its way to the talks. These provocations predictably caused the North Koreans to break off talks. U.S. media ascribed responsibility for the negotiations disruption to North Korean intransigence and “Red trickery.” Stone skillfully exposes how U.S. officials, with media complicity, shifted responsibility to the other side. It is an unsparing picture of official mendacity.

With close attention to detail, Stone never loses sight of the broader picture. The Korean War set the U.S. on the path to militarism and endless war. Stone’s final words in this volume bear repeating:

The dominant trend in American political, economic, and military thinking was fear of peace. General Van Fleet summed it all up in speaking to a visiting Filipino delegation in January 1952: “Korea has been a blessing. There had to be a Korea either here or some place in the world.” In this simple-minded confession lies the key to the hidden history of the Korean War.

The pivotal role of the Korean War

The Korean War is arguably the most consequential conflict since the Second World War. Less well known than the Vietnam War — even being dubbed the “Forgotten War” — its ramifications were immense. It was the start of the Cold War, and it left behind both Korea and China as divided nations, sowing seeds for continued conflict. It made a war economy a permanent part of U.S. society.

Stone wrote as the events were unfolding, so although his judgments were astute, they were necessarily limited. With the benefit of hindsight, it is apparent that U.S. domestic politics of the time were key to the historical development of U.S. imperialism. There were important, sometimes crucial milestones in the process.

Henry Luce’s coining of the phrase “American Century” in February 1941 helped establish the ideological appetite for global dominance that is still debated today. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s maneuvering of a recalcitrant U.S. into the unfolding Second World War was a crucial first step, but it was Truman who transformed what might have been a temporary participation into a permanent commitment to domination. The decision to use nuclear weapons against a defeated Japan was a signal to the Soviet Union, and the world, of America’s strategic military preeminence.

The creation of NATO in 1949 gave the U.S. a Western European military alliance against the Soviet Union, and the Korean War became the other arm of the pincer in East Asia, locking South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan in a U.S.-led alliance against China and the Soviet Union.

In addition, this convenient war also bonded 15 other nations against the Red/Yellow Peril, a cause with intertwined racist and political characteristics. Although some of those countries, such as Turkey, have distanced themselves from the U.S. and are unlikely to be dragooned into another war against China or North Korea, others such as Australia and Britain have shown remarkable, if foolish, enthusiasm for a second round. Moreover, as Stone ably recounts, the U.S. was able to use the flag of the United Nations and have an expeditionary force, over which the United Nations has no control, which is called the United Nations Command. This situation still exists today.

Seven decades on, the major thrust of U.S. strategy is to integrate these two arms of the pincer even further, so that the Western Pacific alliance — primarily Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Australia — can be deployed seamlessly against Russia, and NATO arrayed against China.

The counterpoint to U.S. imperialism in East Asia was the anticolonial movement. Resistance to European colonialism in Asia has deep roots. However, the Japanese colonialism in Asia, starting in the late 19th century and lasting about 50 years, meant that the anti-colonial struggle was a major force in the region. In general, the U.S. rejected traditional colonialism, but its aim was to supplant European and Japanese colonialism and replace it with U.S. dominance.

Since the U.S. could not admit, especially to itself, that it was an imperial power, the author explains that anticolonialism had to be reconfigured as enemy expansionism. Sometimes this enemy was Soviet or Chinese expansionism. At other times, it was expressed in terms of politics, as Communist expansionism. A quip, attributed to Lord Ismay (the British first Secretary-General of NATO), was that NATO was designed “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” The Americans are still there — over 100,000 in mid-2022. But what of the Russians and the Germans? How would Stone have dissected that?

The continuing relevance of the Korean War’s hidden history

Stone read words carefully, comparing texts, noticing contradictions, always testing the rhetoric against reality. Thus, when MacArthur claimed that he was being beaten back by overwhelming Chinese forces— “hordes,” with its racist overtones, was the favorite term — Stone checked that against U.S. military reports. He concluded that Chinese forces were not large, and that the Americans frequently lost contact with the enemy. He concluded that MacArthur was constructing a pretext to take the war into China, which indeed happened. This may well have triggered Soviet intervention, bringing about the Third World War, with MacArthur as the hero of the hour.

MacArthur claimed that such escalation was the only way to stop Chinese aggression. In reality, the aggression was a chimera. China was acting with caution and restraint to protect its border and was keen for peace negotiations. As Stone acerbically put it: “Few stopped to consider what was really happening in Korea. The fact is that the Chinese Communists had again failed to “aggress” on the scale that some feared and others hoped for.”

For Koreans, North and South, the reunification of their country, divided without their permission by the U.S. in 1945, was a cause worth fighting for. China’s aims were necessarily different and more limited. A unified peninsula under a friendly allied regime would be desirable, but one under a U.S. client would be intolerably dangerous, so a compromise was necessary.

Il Sung Kim, and his successors, seem to have accepted that U.S. military is committed to staying in Korea. This meant an armistice in the short term and deterrence in the long term. Rhee wanted the Americans to keep fighting. He boycotted the armistice negotiations, and attempted through the POW issue to scuttle the talks. Kim’s successors have taken a different position on relations with the North (and China and Russia), but at the time of this writing, current South Korean President Suk-yeol Yoon is acting on this issue like a latter-day Syngman Rhee.

The Truman Doctrine was predicated on “containing Soviet expansion,” of which the Korean War was a key test. The opponent was accused of what the U.S. was doing. The postwar decades saw a huge expansion of U.S. political and military power. The Truman Doctrine also served to reduce the complexities of the period, and in particular the anticolonial movement, to a simple binary morality tale, with America being the “city upon the hill,” guiding humankind to a better future. But within this framework, Truman wanted to keep Korea a “limited war” and avoid a showdown with the Soviet Union.

The struggles of those times have been continually replicated. There have been huge changes in the world, of course, in the 70 years since the first edition, but if Stone came back, he would recognize the pattern. The U.S. is at war of some sort — cold, proxy, on the cusp of hot — with Russia, China, North Korea, and many other countries. There are victims of America’s wars all over the world since then, om Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya, among others.

MacArthur is gone but his spirit is still within the military-industrial complex. This behemoth includes not merely the “immense military establishment and a large arms industry” of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s valedictory speech but those in America and overseas who benefit from war or the promise of it. This includes much of Congress, the think tanks, and media outlets, and individuals university professors who benefit from defense contracts — all part of the militarization of U.S. society and its reconfiguration as a national security state.

NATO is a crucial part of this — the an arm of the Eurpopean alliance stretching from South Korea down to Australasia produced by the Korean War, encircling imperial America’s enemies. Established purportedly to defend Western Europe against Soviet expansionism, NATO reinvented itself when the Soviet Union collapsed, attacking in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, and Libya.

It also expanded eastward, threatening the Russian Federation and precipitating the Ukraine War. When Lord Ismay roundly rejected a proposal from the Soviet Union in 1954 that it join NATO he revealed that “keeping the Russians out” had a deeper meaning than resisting supposed aggression.

Nearly a half-century later, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was talk of Russia joining NATO. President Vladimir Putin said “Why not?” and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright said, “We’re not talking about this right now.” A military alliance without an enemy might just wither on the vine, so when there has been a likelihood of peace breaking out — an acerbic comment that Stone uses frequently — there is always an intervention to exorcise that danger. The spirit of MacArthur lives on.

America’s wars, and quasi-wars, are driven by a mix of geopolitical calculation, domestic politics, and the hunger for personal and corporate profit. There is a pervading tension between desire and fear. There is the desire to control the world — showing leadership is a favorite euphemism. There is also the fear of the consequences of war. The struggle between MacArthur and Truman exemplify that, but it constantly manifests itself today. Should the campaign against Russia in Ukraine be limited to a proxy war? Can a limited war over Taiwan stop the rise of China?

Elbridge Colby, a war strategist in the Trump administration and author of The Strategy of Denial, apparently thinks so. He argues that U.S. allies can be bound by a constructed fear of China, and that China can be manipulated into “firing the first shot.” The resulting war would be limited to the Western Pacific, where the buffer states — Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Taiwan — would bear the costs in casualties and damage. China would suffer a bloody nose, which would halt its challenge to U.S. hegemony.

This is a dangerous fallacy, others would argue. Because of local military superiority, China is likely to win such a conflict, which would propel the U.S. to escalate such a war. A limited war is a fantasy.

The issues Stone worked to decipher 70 years ago are still with us. Much has changed in the meantime — the Soviet Union downsizing to the Russian Federation and the rise of China. Today, Stone would still recognize the deception used to mask the actions of powerful actors. Few things are as they seem. Governments lie to the enemy, and to their own people. The Internet and social media have transformed the information environment but the fundamental challenge of penetrating the deception remains. Stone’s pioneering attempt to unearth the hidden history of the Korean War is both a guide for our future, and an inspiration.