Editor’s Note: Leading with empathy is trending as we claw back from the pandemic disaster | By Martha Vickery (Summer 2021 issue)

Popular culture would have us believe that millennials (Gen Y or the group born between 1981 and 1996) are the collaborative types, the ones the who want to advance the well-being of the society. Gen Z is labelled the competitive group, for whom security is paramount. This tendency — if at all true — is blamed on the Great Recession of 2007-2008, which caused insecurity for many, and it is said, shook the Gen Z’s confidence at an early age, causing them to value the cushion of financial security for themselves above the value of making society better.

Are the ones coming up so very security conscious and unconcerned about the greater good? No stereotype is true, of course, however, I am wondering if recent events are blurring the lines of all our generational value systems and pushing us all towards expecting more humane workplaces, a more responsive government, systems that really work for our current reality, a model of leading by empathy.

I remember my son, as a high school student, told me he persuaded a discouraged younger kid on his school’s track team (sixth through 12th graders) to stay on the team and keep trying. He did it by admitting to his younger teammate that he was once the slowest runner on the team. It was true, actually. He did start out as the slowest kid on the team, but realizing that, he skipped the sprint events, and built up his endurance skills as a long-distance runner, eventually running a marathon.

Even as a high school kid, my son’s intuition was telling him that no sixth grader would be responsive to a pep talk intended to get him to go out there and beat the competition. The age differences and skill differences were immense. The competition was too much. There was no point.

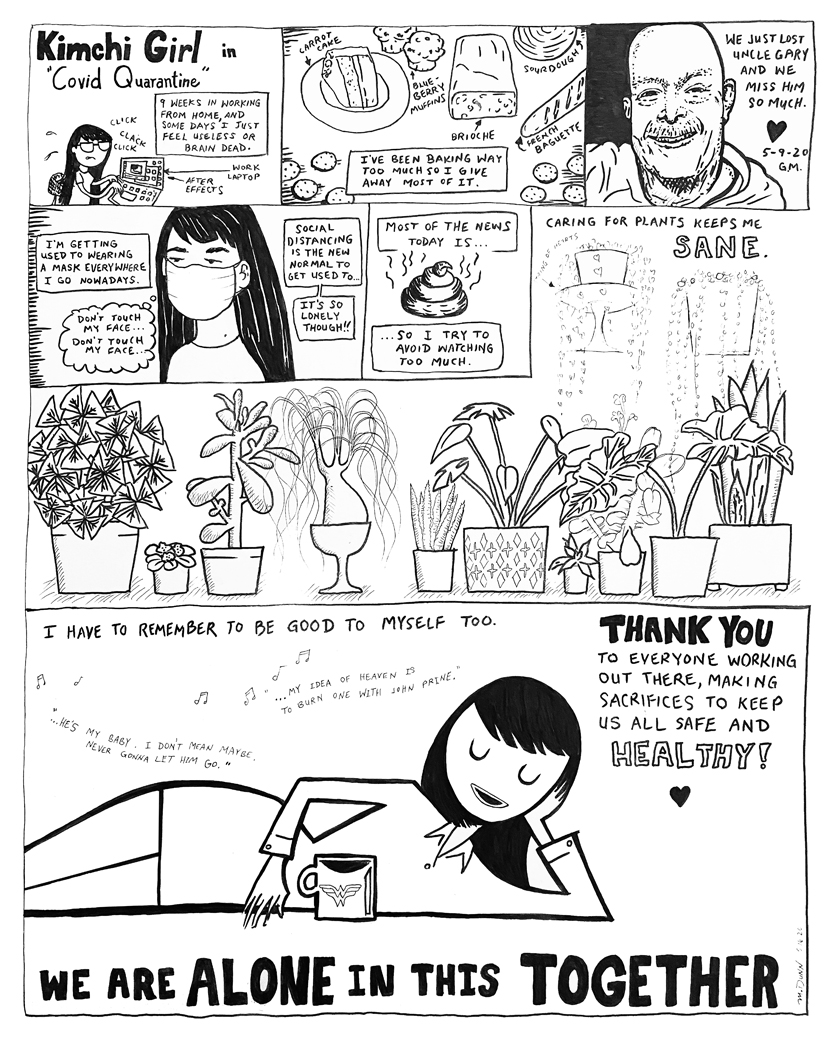

One of the most significant events of this decade, possibly in the lives of all of us sharing the planet today, has been the pandemic. Although it’s not over, we can see some the effects of its permanent changes around us today; it is like perceiving the destruction of an invisible earthquake. A calamity like the one we have been through — are arguably still going through — tends to re-order our priorities. Big enough calamities can reorder a whole society’s priorities.

Already, we have seen effects in our awareness of societal and racial inequities, sensitivity to politics, greater expectations for our health care systems, and our decreased tolerance for how our workplaces run. Its effects have even been reflected in the values of old, rules-based sports organizations like the Olympics.

Can it be that we can push for more models that raise us all at the same time, demanding more in terms of support from systems that are supposed to support us? Pandemic social effects are reverberating around us, and are threaded through this issue. Increasingly, although I cannot fully express it yet, I can feel something like a seismic shift.

Just perhaps, is part of this unwillingness to go out there and beat down the competition, like we used to, simply exhaustion? I think we are all feeling the stress of the last 18 months in trying to get by — to not get sick, stay positive, stay employed if possible, pay the bills. The strikes against us have seemed like too much. It could be that.

Haven’t we all felt the bone-tired exhaustion of things seeming to have too many layers of difficulty; a feeling of “I can’t even think about this.” That it’s all just too tiring? Does it make us all a bit more empathetic than we were?

Columnist David Tizard (Punk Christianity, p. 11 in the print edition) noted the countercultural flavor in South Korea of Rev. Dong-Hwan Lee’s recent comments after being suspended by the Korean Methodist Church. The suspension was imposed after a trial (apparently the denomination is so bureaucratic that it has its own court). The infraction of the rules was that the pastor said a blessing for the participants in a Queer Culture Festival in Incheon.

The trial must have been quite unusual. It hit the headlines in June, and Christian progressives globally expressed support, and decried the punishment. Overall, the move was apparently not viewed favorably in South Korea, where more than 70 percent of millennials and the Gen Z age group favor same-sex marriage. My guess is that Methodists are thinking “with everything else going on, our leadership has to go after this guy?”

His denomination’s opposition to his actions was not a surprise to Lee, but the suspension was. “How can a blessing be seen as a sin?” he asked.

This spring, the French Open, another rule-based sports bureaucracy, was caught off-guard when four-time Grand Slam champion Naoko Osaka stepped aside after she was told she would have to have press conferences. She refused, citing mental health concerns, and resigned. During the Tokyo Olympics, Simone Biles, feeling that her mental attitude was a factor in a couple of repeat mistakes in events, told her teammates they would have to win without her. They did. Her decision may also have been strategic, and could have made the way for other teammates, like 18-year-old Sunisa Lee of St. Paul to step into the gap. Lee, who won a gold, a silver and a bronze medal, was celebrated in a hometown parade (photos and new story, p. 52 in the print edition).

It’s all about how you decide to spend your energy — that is the philosophy of Korean adoptee gymnast Yul Moldauer, who used his Olympic opportunity as a way to shine, showing his competitiveness, but also support and understanding for his teammates, who, like him, have had a rough last two years. Moldauer also showed he knows how to avoid putting energy into something, like social media, or circumstances out of one’s control (story, p.37 in the print edition)

The campaign Citizenship4All is the ultimate “leave no one behind” social campaign, and a 100-day “occupation” of the White House (or probably Lafayette Park) was carried out from January to May by a broad coalition led by the National Korean American Service and Educational Consortium (NAKASEC). Advocating for youthful undocumented population used to be NAKASEC’s focus, but, as advocate Glo Harn Choi said, there was a suggestion of “deservingness” there; that U.S.-educated youth had more to contribute than working immigrants. So they dumped the idea. The world needs elders too, not in another country, but in the family. All or nothing is the theme of the current campaign, and it looks like they may get it all if the current budget reconciliation strategy works (news feature, p. 32 in the print edition)

Sejong Academy, the first and still only Korean language immersion charter school in the Midwest, went from 67 students to 360 in seven years with its dedicated staff and winning attitude, and opened a new school building this summer. The founding group fostered a community, not a school of individual achievers, but an empathetic leadership, leaning on the Korean values of “family and community, education, hard work, persistence and respect,” according to School Board chair Grace Lee (see news feature, p. 23 in the print edition). It has also exceeded expectations in reading and math scores, and will graduate its first 12th grade in 2022.

Minnesota’s Senator Paul Wellstone famously quipped “We all do better when we all do better.” Bringing everyone along in a post-pandemic society will make a big difference in recovery from this time. We just have to decide what we want to put our energy into, and what we just can’t do any more.