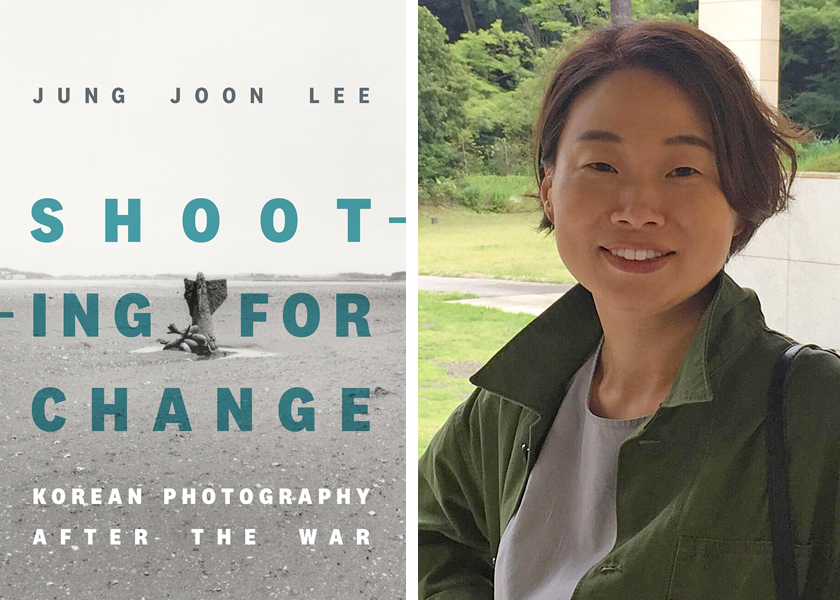

Shooting for Change: Korean Photography After the War ~ By Jung Joon Lee

(Duke University Press, Durham/NC, 2024, ISBN #978-1-4780-5920-2)

Review by Bill Drucker (Spring 2025)

Author Joon Jung Lee ,in this interesting analysis of photographic images in modern history examines how post-war-era photos reflect, contradict, and influence the political landscape and social psyche of Korean culture. Shooting for Change also describes how, in the social media age, images created with cellphone and internet technology became powerful tools for state criticism and social protest.

The author analyzes collective memories captured with images, particularly those attached to the post-war period. The images reflect a post-war state trying to define its own nationality. Through many hundreds of years, Korea had been ruled by or dominated by China, Japan, Russia and later the U.S. The Korean people’s liberation and hopes for self-determination after World War II were short-lived, because Korea was divided and again under authoritarian dictatorship only a few years after the 1945 liberation from Japanese rule.

Lee discusses how perception of images change. When first recorded, an image may have a certain meaning, and with the passing of time, that meaning may be replaced or revised as historical events are re-addressed. Cultural influences, memory, and subsequent events all play into the perspective and interpretation of a captured image as a moment in history.

The author also analyzes how the family is portrayed through photographic images at different times in Korean history, particularly images in which the family portrait showing a conventional family seems out-of-sync or conflicted. Like a Norman Rockwell family portrait is a mismatch with most American families, no idealized image of a Korean family truly matches reality.

Lee discusses how post-war Korea was fragmented – the people and their nation were in an orphan state. There are iconic images of U.S./UN soldiers with Korean children, suggesting the roles of savior and saved, like a father protecting a lost child. From today’s perspective, the same image can suggest neocolonialism, the patriarchal power dominating the helpless child state.

Viewed from an even darker lens, such an image can also be viewed as the war perpetrator deceitfully using an image to portray the salvation of the war victim who would never have been a victim if not for the perpetrator. The author notes that the use of orphans as the face of war, once seen as good Christian intent and good military propaganda, is now obsolete. The state of Korean post-war orphanhood is an image stuck in time. Today, there are no orphans, and Korea is no longer an orphan nation. Yet, the perception of the U.S. as paternal savior, big brother, and military protector remains.

Women’s roles in family images, traditional and modern, have undergone a major shift. As South Korea has risen to the world stage, images of women have also been modernized, though not without a mighty struggle by its women to achieve change. Korean women have chafed against traditional female gender roles for many years.

Iconic images of the past show a mother, either alone or with family, posing in a hanbok (or traditional two-piece dress), with hair in a bun, looking serious and maternal. Today, married women are also pursuing jobs or careers to support their families, and may be college-educated professionals. Like Korea going from orphanhood to statehood as a nation, Korean women have gone from traditional and suppressed to modern, and probably more liberated. They are, however, saddled with the many financial and societal responsibilities that have come with more choices and more education and earning capacity.

The author also analyzes images of social (minjung) movements. She focuses on the term kwangjang, the Korean word for public square. The term also refers to the larger idea of the public forum of ideas. Photography has been a powerful tool for capturing civilian protests from many moments of the 1960s, 1980s and 2000s.

However, the free association of ideas has not been the norm in modern Korean history. State censorship is one of the issues that has marred South Korea’s history as a democracy. During the regimes of (first president) Syngman Rhee and (third president) Chung-Hee Park, a branch of state security handled media censorship, however many powerful images of those times were published nonetheless.

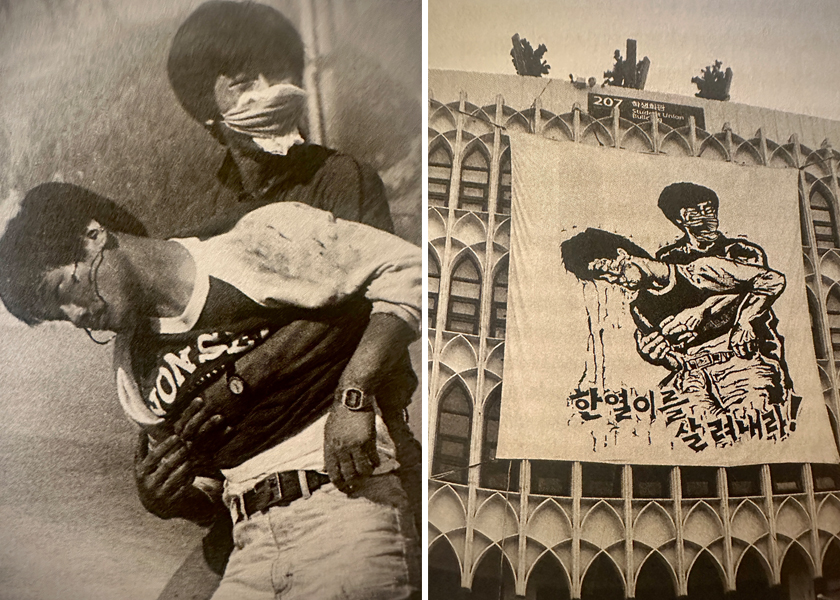

During the 1987 democratic movement, photographers captured many images students and activists being beaten and abused for the cause. In one famous photo, student Hanyol Yi is held up by another student after being hit by a tear gas canister; the image speaks volumes of the violence and oppression of those times.

As South Korea turned into a modern, industrial state, communications technology evolved and important documentary videos and photos were disseminated through the internet via cellphones. These tools created a wider kwangjang, or public forum, creating an empowered and networked community.

Candlelight vigils from the time of the protest of the Geun Hye Park administration were captured the demonstrations in many iconic still photos and videos, which drew global audiences. The months of persistent protests led to her impeachment and removal from office in 2017.

The author also points out how images have shaped the public criticism of the division of Korea, particularly through photos of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), and the military-supported camptowns that still exist near U.S. bases in South Korea. Both subjects present a troubling sense of transnational militarism.

The DMZ was once patrolled by the U.S. troops, but it is now guarded by South Korean troops, although border policy is still influenced by the U.S. Photos depict the DMZ as a strange contrast of military border tensions and “must see” tourist attractions. Many tours, including family tours and adoptee tours, may include a trip to the DMZ.

The author criticizes the persistence of the DMZ as a theater of repetition. Rather than being a place where anything progresses or is resolved, the DMZ is an unresolved place where images of war, the failures of militarism and diplomacy are revamped into tourist attractions with a rewritten history. Similarly in Vietnam, the enemy tunnels U.S. troops had to crawl through are now guided pay tours. The real issues are muted, often promoted through the same images once used to condemn.

Starkly contrasting the U.S. commitment to protecting South Korea and maintaining regional peacekeeping are the persistent camptowns catering largely to U.S. servicemen, providing soldiers with the local comforts of alcohol, food, and sex workers. It is a netherworld that is neither confirmed nor denied by the U.S. military or South Korea military.

These camptowns have been gentrified and Americanized, but there is a darker agenda of social stigma, violence, and official denial of U.S. military culpability. The sexual workers are referred to as mikun wianbu (comfort women). The phrase smacks of hypocrisy against and disrespect for the Korean and other Asian women during the World War II era who were forcibly conscripted into military sexual slavery by Japan, and often referred to as “comfort women.”

Older images of camptowns show soldiers in uniform fraternizing with young women in American-style dresses and heels. Images from recent years show young women in jeans and more casual clothing, but the repeating image of Korean women and male U.S. soldiers is symbolic of militarized colonialism, unequal power and sexual exploitation of women.

The emergence of camptowns occurred due to economic exigency, but when the persistence of such places in the next generation is tragic, and hints of a subgroup of society doomed to be living on the fringes. They are not happy Polaroid moments; rather, they project an unsympathetic ugliness, devoid of any aesthetics.

Photojournalism has matured with each war in which Korea was involved. Photographers capture military activity intended to stay in the shadows, such as documenting mass graves of civilians, exposing the brutality of weapons like napalm which indiscriminately maimed children and other civilians in Vietnam, witnessing Korean students raising their blinking cellphones in silent uprising. Such images have immediacy, and can question the integrity, and challenge the legitimacy of continued military presence in one picture. Images have a temporal quality that the often author refers to. They are records of a place and time, but can evolve with age into social and political criticism.

While there is enough fuel in this analysis for some fiery rhetoric, Lee avoids it, and instead asks leading questions for the reader to ponder. Overall, this contemporary discourse digs into enduring questions of how images affect our social consciousness.

One critique might be that the photos are too few, and that the reader might wish for a large selection of images on a certain topic. However, the author’s analysis is thorough in addressing key social and political themes, and giving critical context on how photos have shaped the way we look at moments of modern history.

Author Jung Joon Lee is an associate professor of the theory and history of art and design at the Rhode Island School of Design. She is currently co-editing a book entitled Queer Feminist Elsewhere; Decolonial Making in Transpacific Art, which will feature works by scholars and artists in Korea and in the Korean diaspora.

She has published in such journals as History of Photography, photographies, Trans Asia Photography, Journal of Korean Studies and PhotoResearcher. Lee’s recent publications include essays on grieving as artistic collaboration, and on the Cold War and images of transnational adoption.