Learning DPRK’s popular culture and arts at a university summer school | by Martha Vickery (Summer 2022)

A collection of Ph.D. and Master’s students, Korean studies instructors, and working people with interests and expertise in Korea formed a small community for two weeks in May for a unique course in the arts and popular culture of North Korea.

The students came from Romania, Chile, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Canada and the U.S. to attend the North Korean Summer School, held at York University in Toronto. The class was the brainchild of Dr. Thomas Klassen, a professor of public policy at York, who drew on his connections across academia to market the course to a global audience.

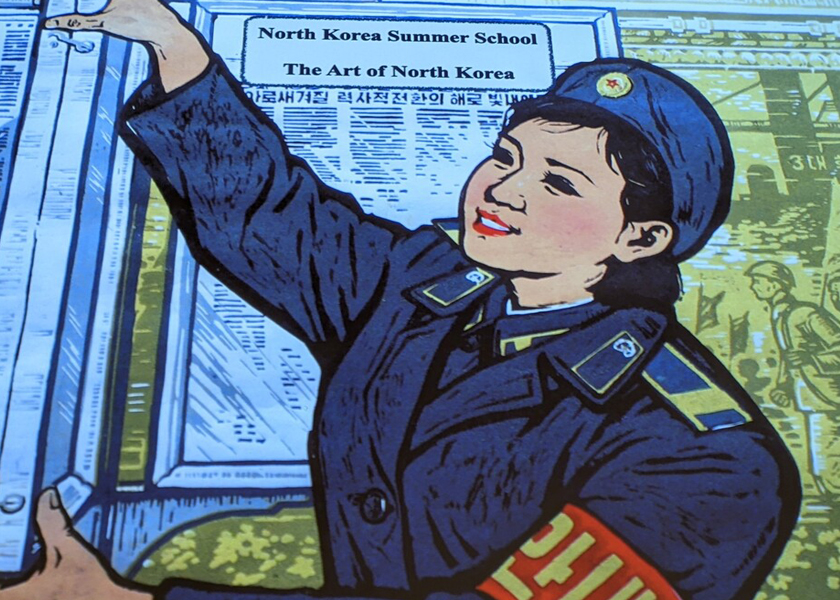

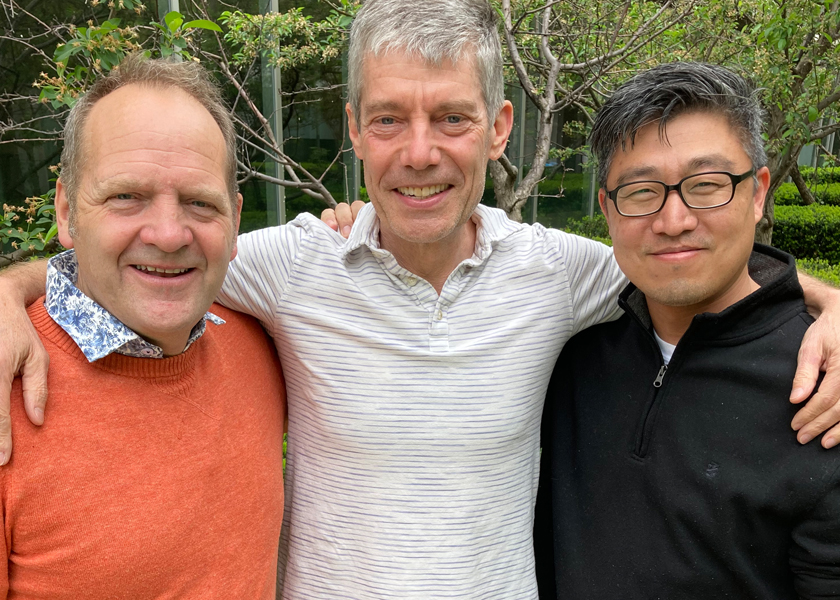

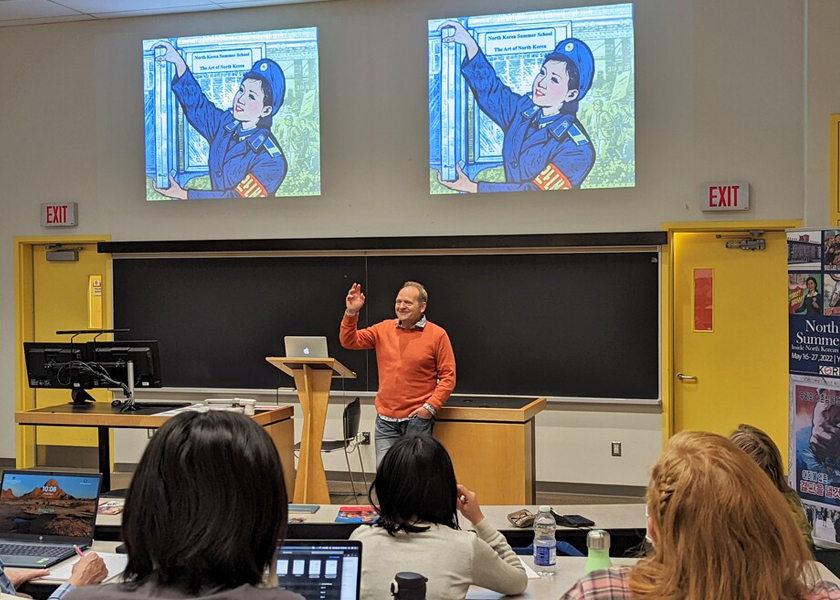

The class, entitled North Korea Summer School: Inside North Korean Literature, Art and Film, met for nine full days in May, five of which concentrated in the history of literature and film, taught by Prof. Immanuel Kim, who lectures at George Washington University in Washington, DC, and offers annual course about the film and literature of North Korean. The last four days were taught by artist/curator/filmmaker Nick Bonner, who for 30 years has worked in North Korea as a tour guide with his company Koryo Tours, and as an art project facilitator and documentary filmmaker under the offshoot company Koryo Studio. Bonner, who is British, gave an overview of his films and other creative projects.

Pushing for something different

Klassen said that when his university received a grant to create a summer school program on a Korean topic, he pushed for something on North Korea. Living for five years in South Korea and traveling once to North Korea in 2016 showed him that “South Korea is only a part of the Korean story,” he said. He did not want to the program to be about the typical topics of security studies, the arms race, or politics, but rather about the people and the culture.

Klassen imagined a class comprised of a diversity of students, that would be open to “someone who has an abiding, long-standing interest in the topic.” He also guessed that there would not be enough people in Canada or in any one country to fill a classroom about this unique topic. “The people who would be truly interested would be spread out across the entire world.”

Klassen used the considerable contacts amassed by York University’s Korean Studies program to advertise the summer school to Korean Studies departments and other contacts in many countries. He also searched for two instructors, each of whom would bring a different kind of expertise about North Korean people and culture. “Immanuel Kim and Nick Bonner were the two obvious choices who kept coming up,” he said, “and I’m so happy they were both able to do it.”

Peeling back the layers

Immanuel Kim, a professor of Korean literature and cultural studies at George Washington University, said his background is in North Korean popular culture, including film, TV dramas, and modern literature. In May 2020, he published an English translation of the North Korean novel Friend, which received some early acclaim. The author, working North Korean novelist Nam-nyeong Paek, had an in-person visit as part of their collaboration to deliver the novel accurately to English-speaking readers. The story unwinds the interior life of one judge, who is responsible for adjudicating divorces, and about several couples assigned to him for a decision on whether their divorce should be granted.

Kim said he has also received some attention for how he introduces North Korean history and modern life to U.S. college students through its films, literature and other vehicles of popular culture. Kim said he modified his annual 15-week North Korean Society and Culture course to fit into five full days for the York University summer school class.

Teaching about the modern culture of any country is like trying to hit a moving target, since all cultures are dynamic and changeable, Kim explained. North Korean culture has multiple layers. “There is the culture of Pyongyang as the capital city, the culture of remote villages, the culture of men and of women, and of schoolchildren – all kinds. Then all the different jobs – the culture of the military and of factory workers,” Kim said. “My exploration of literature I think shows the various layers, including many different aspects of society. So it doesn’t mean we have a comprehensive look at culture through literature, but it’s at least a nice glimpse into it.” It’s his favorite topic to teach, he added.

Although the course presents a “very narrow window” into North Korea, Kim said, “hopefully it’s insightful enough to open students’ minds to the country. You know the typical thinking about North Korea is that it is a crazy country or it has crazy people. But hopefully, through this summer program, we can learn that they are just as human as we are, and that during their lives, they also go through pretty wild and interesting things.”

Kim says he is also interested in “blowing up the myth that North Koreans are cut off and uninformed about the world. There is news reporting, and North Koreans do hear it, even though North Korean media has its own take on world events.” Part of the class included some examples of North Korean state media’s reporting of recent key world events.

Kim said he thinks having tour guide/filmmaker/art collector Nick Bonner as a co-lecturer was the “biggest attraction” of the course. Kim stayed for the second week of the class, expressly to hear Bonner’s lecture, which included lots of photos and film clips. “It’s something you will never find in books,” Kim said.

Making documentaries in the DPRK; an art form in itself

Since 2001, together with film director Daniel Gordon, Bonner produced three award-winning documentary films, for which he was granted an unprecedented level of access to the lives of the participants. The three films (all of which have been aired on public television in the U.S.) include The Game of Their Lives, (2002), A State of Mind, (2004), and Crossing the Line, (2006). In 2012, Nick served as co-producer and co-director of Comrade Kim Goes Flying, a non-propaganda girl-power-themed feature film which was released in the DPRK, and in the west, and was produced by a collaborative Western-Korean cast and crew.

Bonner has one of the world’s most comprehensive North Korean art collections. His DPRK art exhibitions have been in Toronto and Hawaii. He has also collaborated with Pyongyang artists, commissioned pieces for international exhibitions and advised on art publications such as Arts of Asia.

A crucial ongoing project includes establishing a museum of North Korean art; it will house the more than 8,000 pieces of art and ephemera he has amassed during his long career. Bonner has tentatively identified a location in Tuscany (Italy) for the museum, which would allow access to Western and Asian visitors, including (due to Italy’s diplomatic connections) both North and South Koreans.

In addition to his discussion of making films and doing other projects in North Korea, Bonner showed and described the sophisticated poster art of North Korea, and its promotion of various social and economic state campaigns over the years. He also delved into North Korean modern architecture, painting, sculpture and graphic arts.

Particularly interesting was the advertising art from a society where actual competition between manufacturers of products is practically non-existent. Bonner also produced two books of art prints in recent years: Made in North Korea, about paintings and poster art; and Printed in North Korea, about advertising art.

Doing business in North Korea

Bonner described how he has built trust with his North Korean business partners through frequent tours and collaborative small projects. Koryo Studio’s access to ordinary North Korean citizens, for example, the families of the girls who appeared inthe film documentary State of Mind, was achieved due to those early partnerships. State of Mind told the story of the lives of two young gymnasts, and the long years of disciplined training required to appear in the Arirang Mass Games, a unique stadium show in which huge groups of young acrobats, gymnasts and martial artists participate. The spectacle symbolizes the North Korean collective will and ideology.

Bonner also included unofficial and fun film clips, screen tests, cinema verite films of the busy city streets, and Pyongyang people in the subway or waiting for a bus, to capture the flavor of life in North Korea. One candid film was of a meeting he held while trying to decide on a direction for a script. The friendly negotiating in it, he said, shows how one must have a sense of “understanding normality in abnormal situations. We all understand there are restrictions in working in North Korea. The question is how to work with those restrictions and still do your job.” Bonner said he learned when to back off, and also how to be a little pushy when required, to achieve the kind of access, support, and resources needed to do the work.

The depth and breadth of what their small Koryo Studio has been able to do is “incredible,” Bonner said, “and not just because of us, but because of the work of so many North Koreans.”

In recent months, the China-based Koryo Tours has been all but shut down due to the pandemic; Koryo Studios is still in operation, doing some small projects. They keep in touch with North Korean partners, just to share information. They are trying to keep the business nominally open Bonner said, because once closed, it is difficult in China to get permission to reopen a business.

Getting financial backing has always been problematic, Bonner said, due to perceived instability due to the lack of a coherent policy by the West (particularly the U.S.), toward North Korea. The lack of support for projects, Bonner believes, is not due to anything legally prohibitive, such as sanctions “it’s only because it has the words ‘North Korea’ linked to it.”

Bonner remains hopeful, he said because North Korea is leaning toward greater openness to foreign technology investments and business partnerships. “If North Korea keeps going in the same direction, it will go the way of China, and open up,” he said, which, in the presumed absence of a pandemic, could mean a better chance for business in the future, and more ways for foreigners to get access to the country.

A globally-sourced student cohort

The summer school class students arrived from nine countries, and included academics involved in everything from Korean and Asian studies to dance, information science, law and anthropology; it also included career researchers, artists, filmmakers, journalists, an art museum curator, a corporate trainer, and an IT engineer.

Japanese reporter enrolls to broaden knowledge

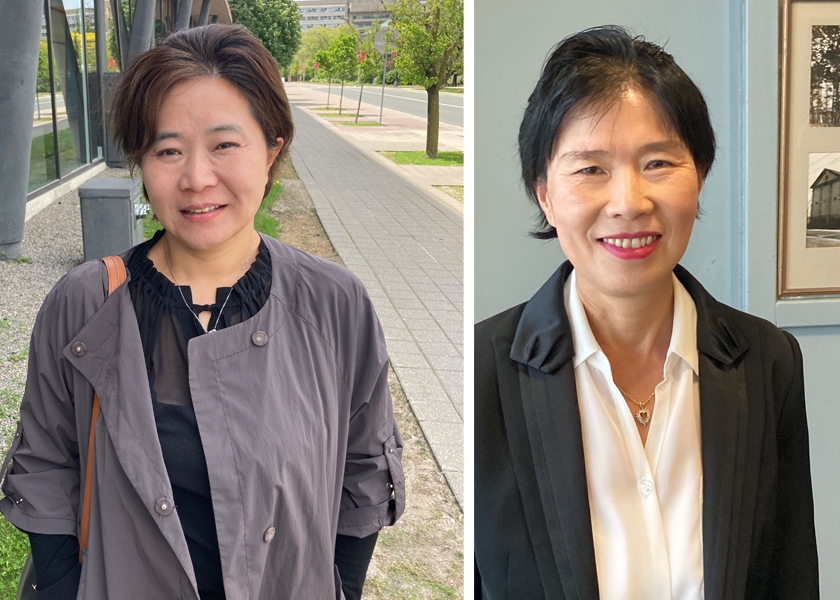

Participant Sachiyo Sugita, a broadcast reporter for NHK-TV in Japan said she got word of the class from an acquaintance in the Zainichi community (ethnic Korean residents of Japan). She was immediately interested, she said, because she knows there is much she could learn about North Korea, a neighboring nation.

She recalled a perplexing reporting assignment from about five years ago, she said, when “empty wooden boats drifted into the coast of Japan.” The boats were thought to be from North Korea, and their lightweight design was unsafe for the open ocean between North Korea and Japan. It was assumed that the crews of fishermen were fishing in a disputed area of international waters, and were washed overboard in heavy seas. She had little social or historical context through which to interpret that event, but often thought about those inadequate empty boats, found so far away from their home ports.

Sugita said, as an adult, she realized she was not taught about the anti-Japanese movement in North Korea (a movement that stems from the Japanese occupation of 1910-1945). In general, she said, little history of North Korea is taught. Although there are academic experts in Korean studies, very few study North Korea.

Within Japan, she said, the story about World War II is that “we lost the war and withdrew,” with little detail taught about Japan’s role in invading and occupying many countries throughout the Pacific Rim. The official position about North Korea in Japan, she said is often expressed as being dependent upon a resolution of the issue of missing persons from Japan, either known to be or thought to be abducted by the North Koreans. “Most of the time, we learn about the abductees, and how we were victims,” she said. “They say we cannot have a relationship with North Korea until the issue of these abductees is solved. So, we’re the victims. That’s what we hear.”

During the first week of class, instructor Immanuel Kim presented his version of how North Koreans view Japan “and it was something different from what I had learned,” she said. Viewing Japan and Northeast Asian history from a different perspective is useful in general in her work as an international assignment reporter, she said.

Learning more about two divergent cultures

Soojin Park, a Ph.D student at South Korea’s Ewha University, is majoring in Korean studies with a specific concentration in North Korean society and culture. She heard about the class from her advisor, and thought the summer school class would be perfect for her, she said. She has access at Ewha to coursework in political, economic, and peace and reunification studies topics on North Korea, but little coursework about the fine arts and popular culture of the society.

Park said she is interested in ways South Korean and North Korean culture have diverged. A good example, she said, was Immanuel Kim’s explanation of the North Korean term uri (the pronoun for “our” in Korean). “For me uri is a very familiar word,” she said, but in North Korean culture it takes on an expanded meaning of “our way,” (uri-shik) which can mean “our North Korean way,” or even “the Kim Il Sung way,” another term for the national ideology.

Meeting the non-Korean participants in the class, some of whom were already knowledgeable about North Korea, was the most interesting part of the class for her, Park said. “When others in our class said they had been in North Korea one or two times, I was just thinking ‘Oh, I want to go there. It’s so sad. And I am Korean. I want to see for myself what their culture is like.’” North Korea has always prohibited access to the country by South Koreans; South Korea has allowed entry into North Korea only for diplomatic missions and special visits, such as brief periods allowed for reunions of families divided after Korea was split into North and South.

Park, who is one year into her Ph.D. program, said she was also hoping to collect some ideas from the class on a future thesis topic on North Korean popular culture.

Two Chilean scholars in law and film studies

Bernardita Gonzalez and Carolina Pedreros are friends and former classmates in a Korean Studies graduate program at Central University (Universidad Centrale), Santiago, Chile, from which they recently graduated. They traveled to Toronto together for the program. News of the North Korea Summer School program reached Pedreros through academic channels. “Since there are not many programs dealing with North Korean cinema and literature in Chile, we decided to apply,” Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez is now in a law Ph.D. program at Central University. From a sociological and justice perspective, she studies how laws are applied, fairly or unfairly, to specific ethnic and racial groups. “My special interest is how North Korean [refugees] are adapting in South Korea, and the particular policies and laws that are regulating the process of integrating refugees into society,” she explained.

There are similarities between South Korean laws purporting to help North Korean refugees accept and adapt to South Korean society, and Chilean laws and policies established to get Chile’s indigenous people to conform to its society, Gonzalez explained. Both nations have introduced laws that apply just to the minority groups. “This kind of adaptation is what interests me, because it’s like an ‘us against the others’ approach,” she said.

In the process to adapt to South Korean society, North Koreans who emigrate to the South have to, in a way, give up their “North Korean-ness,” Gonzalez said. “If you set aside the political and ideological issues, still there is a person who has a culture and a tradition, and you still are making that person erase everything, and start anew,” she said. Whether and how the state imposes cultural erasure on its citizens, and whether that is fair, is a topic of her research.

The class, with its emphasis on looking at a society through its art and popular culture, is a way to know North Korean society better, Gonzalez said. “If I want to work with North Korean refugees in South Korea, this comes with a knowledge of their history, their culture, and their society.” She added, “I do not want to enter into this research with a background only of South Korean culture.”

In her program in Korean Studies at Central University, Pedreros said, she always felt there was “a missing part.” She first heard about the North Korean Summer School program in 2021 (before the program was postponed a year due to the pandemic). It seemed like an opportunity to learn more about the missing part of Korean history and culture.

Pedreros’ academic interest is in filmmaking, specifically in using cinema as a tool for international communication and as a bridge to understanding. North Korea has had a lively film culture throughout its history, and its films have been a key tool for international communication about North Korean people and the state’s specific ideology.

Pedreros said she is interested in a few brief periods of history when North Korean society and Chilean society intersected. One occurred from 1970-73, when North Korea, Chile and Cuba were allies, and when Salvador Allende, a socialist, was the president of Chile. During that time, Allende and North Korean leader Il Sung Kim met in Pyongyang. After a coup in Chile by Augusto Pinochet in 1973, diplomatic relations with North Korea were cut off.

Pedreros said she is also interested in other intersections of South American and North Korean culture. She and Gonzalez are collaborating on a research project based on the Argentinian film Girl from the South (La Chica Del Sur) (2012) by Jose Luis Garcia, about a South Korean athlete who crossed without permission to North Korea in 1989 for a youth sports festival, then back to the South by walking over the DMZ to make a statement about the need for Korean reunification.

Athlete/activist Soo-kyung Lim was sentenced to five years in prison in South Korea for her act of civil disobedience (she was released after three and a half years). The filmmaker follows up his 1989 research in the early 2000s, when he finds the former athlete nearly 20 years later, and discovers that she is a university professor who was elected to be member of the South Korean legislature.

North Korea from the perspective of people’s lives

Participant and native Canadian Craig Urquhart, a Ph.D candidate in the Humanities Department at York University, also works in the Toronto area with North Korean immigrants. Now earning his Ph.D. in the Humanities Department, he said he will eventually write a thesis concentrating on the literature written by refugees, a growing genre of literature, and a topic that has been barely touched in academia.

Urquhart met and began working with North Korean refugees first in South Korea, through connections at work, while employed in the South Korean tech industry for 13 years. A desire to get a Ph.D., to continue to work with North Korean refugees, and to be able to write his thesis in his native language drove him back to Canada, and to Toronto’s York University.

There is one major difference between the issues of Canadian North Koreans, and those of North Korean refugees in South Korea, Urquhart explained. In South Korea, there is no question about the immigration status of newly-arrived North Koreans, although they have many other challenges before them. They become South Korean citizens automatically upon entry.

Once in Canada, however, new North Korean Canadians’ immigration status is precarious. Compared with South Korea, North Koreans in Canada face many issues “but the main one is ‘can I be allowed to stay?,” Urquhart said. In a legal sense, they are not refugees, because they are already South Korean citizens. But culturally and in other ways, they are refugees, and need a lot of help, he explained. “They arrive with nothing, as just another immigrant from Asia. They are responsible for getting by in a society where you really have to bring it.”

Over time, Urquhart noted, North Koreans, like other new Canadian immigrants, make their lives work. “They have houses and favorite art galleries and children in school. You are talking about architecture of someone’s life.” Projects like the one Urquhart works with, Crossing NK, provide legal aid and help with immigration applications to assist North Korean immigrants to build that stable life faster. He listens to applicants’ stories in Korean, writes them in English, and helps them supply the required personal history and other steps to get their applications for permanent residency submitted.

Crossing NK also has a public relations arm, helping North Koreans tell their life stories, either publicly or anonymously, to get more individuals’ stories into the public sphere in Canada, unfiltered and unedited by anyone else.

Urquhart feels that his is a cog-in-the-machine kind of role, but a necessary one. “The thing is that nobody really cares about North Koreans,” he said. “They are on the wrong side of every political conflict, and manipulated by everyone, and at odds with the world. I can’t solve everything, but I can help.”

Urquhart is more interested in North Korea and its people from a human perspective; less from a political perspective. He observed about York’s North Korea Summer School tone and structure that both lecturers admitted how difficult it was to talk about North Korean art and ideology without getting mired in opinion and politics, but tried their best to do so.

“They were motivated and exceptional teachers, and both had very different and coherent sets of material. They presented it very much with a foreign gaze, especially from Nick Bonner,” he said. “I think it would be better if there were more North Koreans involved, but of course I would always say that,” he added.

Two Toronto residents from the North Korean community each gave a presentation: Author Minju Kim (whose book launch party of her memoir Woman from the North was one of several events scheduled for the class) talked about her life in North Korea; and Soyeon Jang, founder of NK Crossing, spoke about her experience of art and popular culture while she was growing up. Both speakers were arranged with the help of Toronto’s Korean Canadian community.

Klassen said extra opportunities for class participants like Kim’s book launch and a Korean film festival were worked into the schedule “to help people hopefully make some long-term connections, because the graduate students will probably spend the rest of their lives doing this – becoming experts and teaching.” The addition of non-student participants from a wide swath of backgrounds “has added a lot of interest to what otherwise would have been just a bunch of graduate students getting together and talking about school,” he added.

The summer school almost didn’t happen due to the pandemic; it was postponed a year, and Klassen outright rejected the idea of presenting it remotely. “There would people from all over the world, and some would have to attend in the middle of the night for two weeks? It would just never work,” he said.

Communications sent from the public about the class were positive overall, he said, and contained some interesting comments. “I got an email from someone who was very upset that we were supporting this book launch and that it would just portray North Korea as an evil place,” Klassen noted. “The individual was making the point that defectors often have very strong negative feelings about the country.” Although he added, author Minju Kim definitely did not suggest that North Korea was “an evil place.”

In choosing participants for the class, he said, some had to be eliminated because there were more applications than places in the class. The screeners decided not to accept applicants who expressed “strong ideological views about North Korea, either pro or con,” he said, due to the risk of using the class as a platform for strong opinions.

Klassen does not think the North Korea Summer School should be repeated with the same content every year; he thinks they should use the summer program as a way to change up annual summer offerings. However, York University’s Korean Office for Research and Education (KORE), which funded the North Korea Summer School, and will offer other courses in Korean Studies each summer.

Other than a surprise birthday party his wife masterminded for the book launch reception, Klassen said, it all worked out as he planned. “In fact, I think it’s the only thing in my life that turned out just as I imagined,” he joked. In his imagination, he said, he envisioned a global group of participants, thought-provoking and edifying content, some fun Korean dinners and other activities, and two enthusiastic and informative instructors who would who engage students in conversations outside of class. Due to some expert planning and a wide network of contacts in the global Korean Studies community, it all came together.

Editor’s note: For more information, see the website: kore.info.yorku.ca, and contact for info: KORE@yorku.ca. KQ editor Martha Vickery was a participant in the 2022 North Korean Summer School.