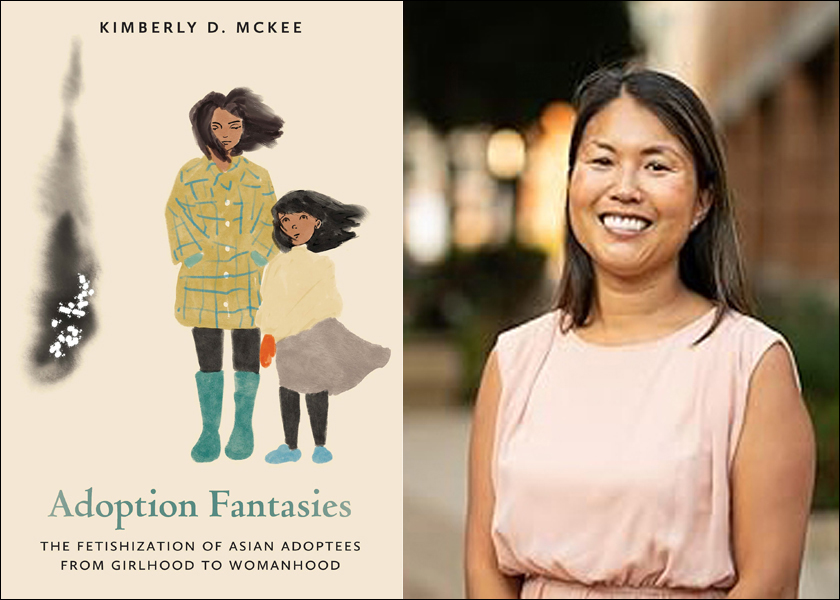

Adoption Fantasies: The Fetishization of Asian Adoptees from Girlhood to Womanhood ~ By Kimberly D. McKee

(Ohio State University Press, Columbus, 2023, ISBN #9-780-8142-5892-7)

Review by Alice Stephens (Spring 2024)

Transracial adoption is a failed experiment in multiculturalism, according to Kimberly D. McKee’s latest critical adoption study, Adoption Fantasies: The Fetishization of Asian Adoptees from Girlhood to Womanhood. Through an examination of representations of transracially-adopted girls and women in popular culture, McKee highlights the contradictory characterizations of adoptees as perpetually-stereotyped outsiders treated as sexualized, tokenized, and humorous objects, even within their own families and communities.

According to the author, “Adoption Fantasies makes visible the nuances that shape the nexus of objectification experienced by Asian women and girls as a lens through which to consider the ethics of representation and the ramifications of how racialized and heteronormative gendered tropes become operationalized on a specific subset of adoptee experiences.”

Focusing on cultural works that feature female Asian adoptee characters, the book begins with an examination of Sex and the City and Modern Family, two popular TV shows that depict the adoption of an Asian baby girl by white families. McKee dissects their plot lines in order to illustrate that “Adoption was never about the adoptee. It was always about the fantasies of adoption held by white adoptive parents.”

In Sex and the City, adoption is presented as the disappointing alternative to having a biological child. After being unable to conceive, the character Charlotte and her husband decide to adopt. Cue the racist reaction from relatives, the misconception that hordes of unwanted third world orphans are just waiting to be saved, and the centering of the white adoptive parents as they have to settle for a Chinese infant.

The adoption of a Vietnamese infant, given the name Lily, by a gay couple in Modern Family, McKee asserts, demonstrates the couple’s “homonormative conformity to ideals of family.” However, by making the adoptee Vietnamese, the show ignores that Vietnam prohibits same-sex couples from adopting. “By overlooking the legal fictions necessary to render their adoptive family possible, Modern Family is complicit in reducing adoption to ahistorical narratives designed to bring joy to white consumers — those viewing the series as well as (prospective) white adoptive parents who see themselves represented in the Tucker-Pritchett family.”

McKee picks out multiple instances of factual elisions and racial microaggressions in the show as Lily’s Vietnamese identity becomes conflated with other Asian cultures, representing the paradox of “racist love,” defined in a quote from Amy Tang as “attitudes of admiration and acceptance that nonetheless work to uphold white supremacy by valorizing nonthreatening attributes like industriousness and docility.”

To frame “racialized sexual harassment,” McKee discusses two movies with secondary female Asian adoptee characters, Sideways and Better Luck Tomorrow. In the former, a transracial adoptee character, played by Sandra Oh, is an object of the white male gaze, characterized as sexually voracious. Pairing with a schlubby white man, she is an expendable sex object that enhances his story of the triumph of white maleness. Her sexual appetite (the white male protagonist crows, “She fucks like an animal”) is presented as a racial characteristic rather than a personal one. And while the characters in Better Luck Tomorrow are all Asian American, that does not shield the adopted female character from “hypersexualized representation” as a prop to explore Asian American masculinity.

McKee’s interpretation of the relentless sexual preoccupation with the bodies of young Asian girls and women is expanded as she analyzes the scandal surrounding Soon-Yi Previn’s relationship with Woody Allen, her adoptive mother’s romantic partner, through the HBO series Allen v. Farrow, as well as the memoirs of her adoptive mother, Mia Farrow; and her now-husband, Woody Allen. Farrow is one of Hollywood’s original transracial adopters, amassing a brood of children from Vietnam, South Korea, India, and the U.S.

Though never married, Farrow and Allen together adopted a white girl, Dylan, who later accused Allen of sexual abuse. Allen’s sexual relationship with Soon-Yi was exposed to the world when Farrow found naked photos of Soon-Yi in Allen’s apartment. McKee argues that Allen’s incestuous behavior was overlooked by the general public who do not recognize that incest can occur in adoptive relationships. “Diminishing the possibility of incest within adoptive families upholds the notion that adoption is somehow a lesser version of biological kinship while overlooking the psychological trauma of incest.”

The author points out that the media blamed Soon-Yi for being a homewrecker, rather than interrogating Woody Allen’s role in the relationship that came to light when and he was a powerful cultural icon at age 56, and she only a college freshman at 19. No matter his claims of not being a father figure to Farrow’s children, he was the long-term partner of Soon-Yi’s mother, and yet it was Soon-Yi who was characterized as the aggressor.

Additionally, McKee believes that Soon-Yi’s claims of physical and emotional abuse from Farrow were dismissed, as they contradict the popular view of transracial adoption as saviorism. “The assertions of abuse also call attention to Allen’s ability to manipulate Soon-Yi to leave one form of abuse for another.” Even her brother, the crusading journalist Ronan Farrow, has “failed to interrogate how uneven power dynamics affected [Allen’s] pursuit of Soon-Yi.”

To show how Koreans and Korean Americans also exploit the adoption trope, McKee turns her attention to the movie Seoul Searching, in which a group of Korean diaspora teens visit Seoul on a homeland tour. Each of the characters represent a stock teen-movie trope: The rebel, the tomboy, the bully, etc. As an homage to John Hughes blockbusters, the film also replicates the American director’s use of misogynist and racist tropes, which the author meticulously details.

As this is the Korean diaspora, there is also a transracial adoptee character, who is successfully reunited with her mother by the end of the film.

The film’s ability to facilitate conversations about the realities of reunion ensures that it departs from other portrayals of adoption, including documentaries that may celebrate reunion with little consideration of its ramifications in the lives of adoptees. Nevertheless, the film reinforces the notion that adoption leads to a better life, because it overlooks the losses and struggles adoptees experience in favor of a flattened perception that absolves the South Korean government, orphanages, and adoption agencies of the conditions that made those adoptions possible.

Finally, the author scrutinizes the popular Netflix documentary, Twinsters, as well as the accompanying memoir, Separated @ Birth: A True Love Story of Twin Sisters Reunited, as “adoptees’ entrance into 21st century U.S. middlebrow culture.” Written, starring, and co-directed by Samantha Futerman, the film tells of American adoptee Futerman’s discovery that she has a twin who has been adopted to France, and of the two sisters’ subsequent reunion.

McKee notes that the story is presented as a heart-warming tale that celebrates adoption and makes the adoptees into cute objects, while never interrogating why the twins were separated from each other or the underlying issues with the South Korean adoption system. Futerman’s adoption papers claimed she had been a single birth, reflecting a troubling lack of veracity in official documents that is commonly reported by Korean adoptees. Rather than investigate the darker aspects of the twins’ stories, the documentary adheres to the popular notion of adoption as a fairy tale. Nonetheless, McKee celebrates the twins’ “biographic mediation, asserting autonomy over what, how, and when details of their adoption are disclosed.”

Though adoption fantasies are deeply entrenched in the popular narrative, the author notes that there have been recent works that are offering a wider and more authentic perspective on what it is like to be an Asian adopted female. McKee observes, “Perhaps what I have learned since embarking on this project is that we will write our way out.” There is an ever-burgeoning canon of works by adopted people to counter the false, sentimentalized narratives that trap adoptee characters as the objects in their own narratives, rather than the subjects.

Though the language can veer into the academic, Adoption Fantasies is an important text that presents a fresh and unapologetic inquiry into a culture that objectifies adopted Asians from infancy to adulthood, perpetuating racism and misogyny under the guise of multicultural love. By training a keen critical eye at widely-consumed cultural products, McKee makes visible the embedded racial and cultural attitudes that have provided the scaffolding for transracial, transnational adoption in America, and asks us all to do better.