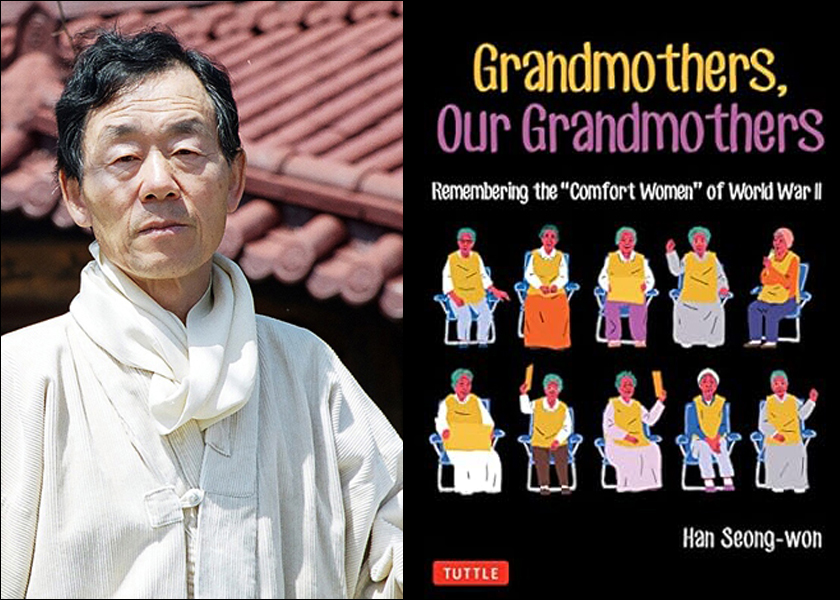

Grandmothers, Our Grandmothers: Remembering the “Comfort Women” of World War II ~ By Seong-won Han

(Tuttle Publishing, North Clarendon/VT, 2023, ISBN #978-0-8048-5663-8)

Review by Joanne Rhim Lee (Summer 2024)

About 20 years ago, artist and historian Seong-won Han’s work on a documentary on war and women led him to the stories of Korean women who survived military sexual slavery by the Japanese, the so-called “comfort women.” These women were abducted and taken to what the Japanese called “comfort stations” to be repeatedly raped by members of the Japanese Imperial Army. The comfort stations were located throughout their conquered territories in Asia during World War II.

In 2019, he interviewed about a dozen of these women, who were in their 80s and 90s; he also drew portraits of them. Han compiled these drawings, interviews, and accompanying text into the slim but powerful volume Grandmothers, Our Grandmothers: Remembering the “Comfort Women” of World War II.

Though Han’s book may look like a graphic novel, as much of it is formatted in cartoon-like panels, he treats his interview subjects with great reverence, introducing each halmoni (the Korean term for grandmother) at the beginning of each section with a color portrait and short biography. Some of the women are depicted in simple line drawings and a stark black background, and others are depicted in more detailed paintings with gorgeous backgrounds.

Rather than focusing on the years of terror and violence through which these women suffered, Han’s goal was to focus on their strength and resilience, and the new lives that they created after the war ended. He wanted to write about the women as regular halmonis, mothers, neighbors, and friends, whom readers may have encountered without knowing anything about their past lives.

Despite Han’s desire to focus on the positive, there is no denying the horrendous suffering that these women endured, and he includes their painful but important histories in his narration. For example, one of the interviewees, Gab-soon Choi, was only 15 years old when she was taken by the Japanese Imperial Army to a Japanese base camp in Manchuria, where she suffered unbelievable atrocities. After the war, she walked south to her home, traveling for more than four years, begging for food along the way. She lived the rest of her life alone, until her death in 2015 at the age of 96. Han’s drawing of Choi is breathtakingly beautiful, as she sits looking up at the stars, waiting for the apology from the Japanese government that never came.

Another interviewee, Gun-ja Kim, was born in Pyeongchang in 1926, and at age 17 she was already engaged to be married when she was kidnapped and transported to a Japanese comfort station in China. She attempted to escape many times, but was beaten each time, becoming deaf in one ear. After the war ended, she returned home to her fiancé, but due to the shame, he committed suicide. Her baby daughter also died at only five-months old. She lived with these multiple sources of pain until she died in 2017 at the age of 91. Still, she spent her life advocating for others, and donated her life savings of 100 million won ($760,000) to a Korean foundation to help students pay their tuition. Han uses wide brushstrokes and only four colors to paint Kim, whose eyes twinkle with joy in her portrait.

Most of Han’s drawings are in a simple comic book style, but he includes about 10 more realistic paintings of the grandmothers at the end of the book. Perhaps they had a say in how he depicted them, as their personalities seem to emerge here, either playfully in a field of flowers, regally in a full length flowing hanbok, or a close up showing gray hair and the deep creases of both hardship and strength. The subject matter is difficult, but the end result is not to be missed.