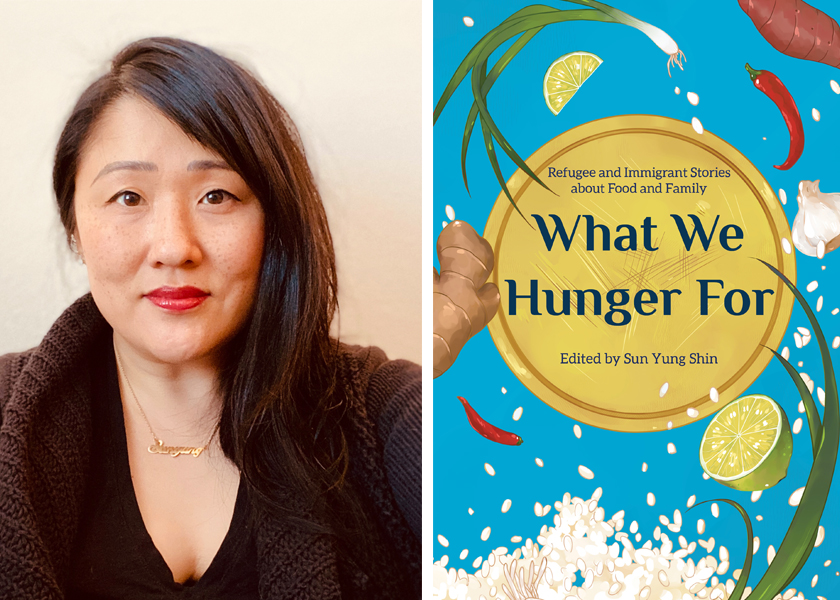

Author Interview: Minnesota anthologist collects stories from immigrants on the foods of their native land | By Martha Vickery (Summer 2021 issue)

The food of one’s native land means love, home, nurture, healing. But it is trickier than that, especially for immigrants. It also involves generational and cultural trauma, grief, loss, abandonment, and sometimes, with persistence, reconciliation.

The ways in which immigrants and refugees treasure, forget, or bury the memories of a left-behind culture, and the role of food in hanging onto, however tenuously, one’s culture of origin, is a central theme of 14 nuanced stories by Minnesotan writers of color in the anthology What We Hunger For: Refugee and Immigrant Stories about Food and Family, edited by Minnesota poet, author and editor Sun Yung Shin. Some contributors to this collection are immigrants, other are the children and grandchildren of those who were refugees from their homelands.

A Korean adoptee, Shin embraces Minnesota life as a theme through this anthology, as well as in the 2016 essay collection she edited, A Good Time for the Truth: Race in Minnesota. She has also published two poetry collections of her own work with a third on the way, and edited the anthology Outsiders Within: Writings on Transracial Adoption.

That the contributors in What We Hunger For are all Minnesotans was partly happenstance; immigrants have many common experiences no matter where they live, she observed. It is a universal book overall, but its Minnesota references to iconic places, foods and symbols, such as the State Fair butter sculpture competition Princess Kay of the Milky Way, lend a touch of the familiar (and sometimes zany) for Minnesota readers. It also describes the diversity of today’s Minnesotans. A Good Time for the Truth and What We Hunger For were both printed by Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Shin said she wanted to produce the kind of book she wanted to read, but could not find. “There are plenty of books by professional chefs and food writers. I wanted to do something different that I would be able to do,” she said. “I wanted it to be good writing by people like me; people who are interested in looking through the lens of food at the refugee and immigrant American experience,” but not necessarily from a food professional’s point of view.

The editor cited many layers of life experience that led her to this topic, from raising and feeding two children (now 20 and 24), to growing awareness of society’s disconnect with the earth and where food comes from, and a year-long class on permaculture she has taken recently. She got interested in food sovereignty, sparked by a trip in 2007 with the Korean American organization Nodutdol, which brings groups to visit South Korean farming and food cooperatives to learn about labor rights, demilitarization, women’s and LGBTQ rights, and the longstanding stable, local, organic food movement there.

Shin recalls going to Pyongtaek during that trip, where farmers whose families farmed the same land for many generations were displaced to make way for a U.S. military base. “It was a profound experience for me be there and see how the military has murdered nature and has taken the livelihood and traditions of these people,” she said. As an immigrant Korean adoptee, she said, “I had never been part of an invitation to have a relationship with a place.” Any such relationship is complicated by “the racism and xenophobia in the U.S. and the belonging in general, let alone [belonging to] the cycles of a place,” she added.

Shin said her family always had a garden, so she grew up with awareness about growing vegetables. While working on A Good Time for the Truth, she said, she was struck by an essay by activist Diane Wilson (who contributed the essay Seeds for Seven Generations), which described urban native children “who don’t even know that food comes from the ground.” Working with Wilson on various projects, Shin said it impressed upon her how critical it is to restore a right relationship with the earth.

In accepting promised stories for the book, “I had no idea what people would say,” she said. “I was just really interested in what they want to say about food. She was looking for a nuanced view, she said, “rather than ephemeral Twitter conversations, or professional journalists writing in food magazines.”

She encouraged each of the contributors to dig in and get at “what regular people are thinking – what are we dealing with?” And in regard to food, “what does this have to do with our grief and longing and our mixed feelings about it?”

It was a lot to ask of writers at that time, for just a small honorarium, Shin said. It was the pandemic, people had a lot to do, and to worry about. Most were writers with full careers; Shin hopes to offer some of the available writers opportunities to engage with readers at reading events, as a way to give something back.

Shin said talked with each writer about how she wanted a final product that avoided any ephemeral descriptions of cultural food traditions. She steered writers from any romance, or tourism-oriented notions about food, and specified that it would not be a recipe book, although the anthology includes a few approximate (and often humorously vague) recipes and descriptions of how the writers or their loved ones make a favorite dish.

V.V. Ganashanathan’s The Measurements, is about how, paradoxically, there are no measurements. His hard-won “recipe” for curry chicken is more about how it is important to watch and learn one’s culture and its food, rather than imitate it with a recipe. With his mom’s help, and a technological boost from video calls, he eventually assembles a kind of recipe that includes a pinch of this and that, and “an arbitrary amount” of everything else needed to make an adequate curry.

Some of the writers in the anthology seem confident in carrying forth their homeland food traditions, such as Ugandan American reporter/storyteller Senah Yaboah-Sampong. He writes of how immigrants are challenging mainstream narratives of food and culture “with the complexity and dynamism we feed to one another and season to suit our palates. We learned from watching our parents in the kitchen. It is what we’re made of.”

Just as interesting as the confident foodies are the essayists who seldom or never watched parents or other family cooks in the kitchen, either because they rejected the cultural knowledge offered to them, or never had a chance to absorb it. Some are annoyed at the paltry food knowledge left to them by their immigrant forebears.

Writer Lina Jamoul, in her Fragments of Food Memories; or Love Letter to My Dad, blames her limited recipes on her parents’ steely non-conformism. While her father prided himself in rejecting Syrian/Arabic traditions of patriarchy, “my mom took pride in saying she didn’t like to cook – almost as much pride as my dad took in being a good cook.” Illogically, her mother later told her that she was also proud of putting home-cooked meals on the table even though she hated to cook. She was “simultaneously proud of these two different facts that seemed to contradict each other.”

The anthology also includes Hmong American writers, members of the Twin Cities most populous Asian American group. Writer May Lee-Vang reports that she somehow failed to absorb Hmong folk traditions. As a teen, she disliked having to attend various traditional ceremonies, although she loved the special food. She describes arriving at adulthood, suspecting she is ignorant of cultural knowledge that may be important to know. She knows what dishes go with what ceremony but admits to not knowing exactly what the ceremonies are about.

At the end of the story, at around age 40, Lee-Vang finds herself at such a ceremony for her dad after his death, surrounded by food, wondering if her dad has successfully crossed over, as the ceremony has promised. There are no elders to ask, with parents and grandparents dead, others absent. She remarks to her husband that there are no old people present. “We are the old people,” he tells her.

Shin observed about this and other stories, that there is a phenomenon of immigrant elders dying young, many before their adult children have a chance to benefit from their memories and accumulated knowledge. Dislocation, trauma, hard work and poverty often take their toll on the immigrant generation, she said.

Kou B. Thao, described in his bio as a Hmong healer, writes how hot short-grain rice doused with cold water, a children’s dish in his culture, is still soul food to him. In a very vulnerable essay, he describes a turbulent youth during which he and his siblings experienced food deprivation, followed by too much staying at home alone, and too many junk food meals, while his parents worked at numerous jobs. His weight grew as he approached puberty; he also realized he was gay.

His father’s stories of a painful past during wartime were “weapons of guilt” for Thao and his siblings as children. Only when older did the writer understand that “my parents were the ones assaulted by guilt, stemming from not being able to provide food for my siblings during those difficult times.” Thao writes that his relationship with food was healed in Thailand, while working for a non-profit Hmong youth outreach organization. Food was special, it built community, brought joy, reinforced to him the radical hospitality of his culture, and “I finally learned what it meant to be Hmong.”

Shin thrives on variety; her latest book, The Wet Hex, was recently published. She is also co-authoring a children’s book with Diane Wilson and two other authors, Where We Come From, about forced migration, enslavement, and other historic human rights topics. Currently she teaches an Asian American film class at the University of Minnesota, and next year will be a visiting distinguished professor at Carleton College in Northfield.

Shin admits to being addicted to anthologies. “I am always delighted, astonished, humbled and intensely interested in writers’ stories,” she said. “And even if you know somebody really well, you don’t get to ever just listen to someone one hour straight. That’s the great thing about a personal essay. They unspool their story, and you can just listen.”