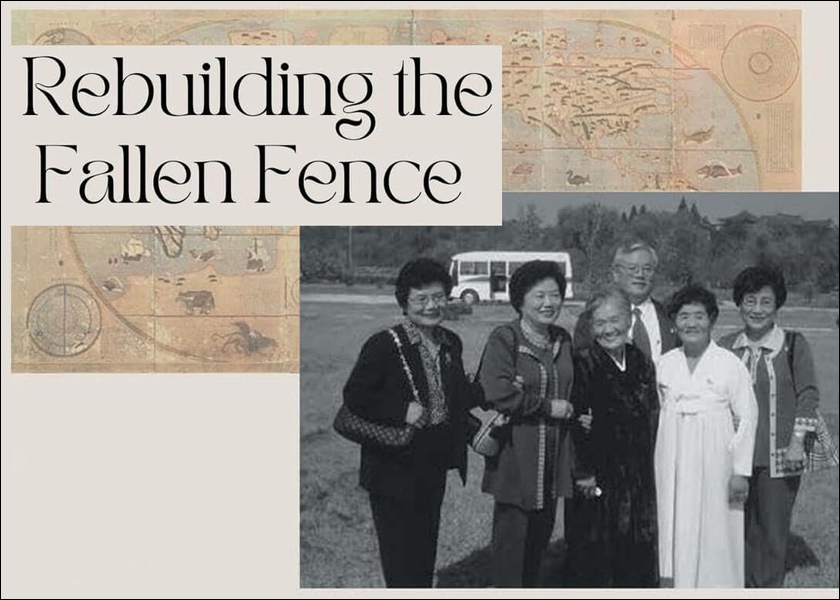

Rebuilding the Fallen Fence: A Korean American Family ~ By Suk-Chung Yu

One pastor reflects on a family torn by war, and reunited a century later

(Covenant Book, Murrell’s Inlet (SC), 2025, ISBN #979-8-8911-2481-3)

Review by Bill Drucker (Winter 2026)

There are always stories of human resilience, courage, and compassion in the midst of a national crisis. This is one of them – a detailed memoir of the Yu clan, a history that begins in the Japanese colonial occupation, and extends to modern times. Despite the trauma and devastation of war, with family members scattered across the globe, this family sticks together, despite separations of many years, and its reunification story is inspiring.

This year 2025 marks the 80th anniversary of the division of Korea and the 75th anniversary of the Korean War. Despite the internal advancements of the two Asian states, there is today still a truculent and unresolved political crisis on the Korean peninsula. Unification and a lasting peace is more distant than ever before. War looms as both states escalate their military resources.

The narrator, now-retired Rev. Suk-Chong Yu, recalls in the narrative how his family survived and thrived over the decades and generations. It is a legacy of family ties that were disrupted but never disengaged. The expression in Korean, reflected in the title, about “fallen fences” suggest the many times the family was separated, stressed, and the time and effort required to rebuild it.

Yu provides two narratives in the memoir. Part One deals with his Yu clan, starting with the family’s peaceful life in Musan, near Paju, within commuting distance to Seoul. The Yus were recognized in their community and church. The family enjoyed high social standing and their children were educated.

The Yu clan witnessed the Japanese annexation of Korea, and the division of the country into two states. Although the family stayed together, the devastation of the Korean War deeply affected their family, as it did nearly six million other Koreans. The family began to splinter as the parents died and siblings were disconnected. Suk-Chong Yu’s eldest sister, Hee-jung, and second sister, Hee-sung, defected to North Korea. Without parents to insist the clan remain cohesive, the siblings were persuaded to send the youngest brother, Suk-young, to America for adoption. He would be known later as David.

In unwinding David/Suk-young’s narrative, the author reflects on Korean overseas adoption, including family, identity and citizenship. Yu describes how important cultural and heritage are, and how adoptees deserve continued support. While adoption may have been the best course of action for the youngest brother at that time, the emotional cost and sense of loss to the family was high. The brothers would meet again later in life, as would the older sisters still in North Korea. All created their own lives and formed their own families.

Yu’s other siblings went to Europe and America. His fourth sister, Hee-young, migrated to Germany in the 1960s. Hee-young worked as a nurse and her husband labored in the mines. The pattern of their lives is very similar to other Koreans who became guest workers in Germany.

Another sister, Hee-sook, and her husband pursued the American dream, initially facing language and culture barriers and racial discrimination. With the help of the Korean American church, Hee-sook and other Korean immigrants slowly adjusted to and succeeded in a new society.

Part Two focuses on Yu’s personal journey. He was a good student from a good family, who eventually pursued theological studies. Yu never lost sight of his fractured family – the members in the North, the younger brother brought up by a white, American family, and other siblings in America and Europe. His wish was to reunite them, and he eventually achieves it.

Yu describes how his education and training lead down a secular path. War, personal injury, lost of family move him toward a new path, one of spirituality. He entered a seminary, and His early career included serving as editor at the Christian Literature Society of Korea. He later took an academic position at Chung-Ang University. He describes his successful career a pastor, publisher and editor, writer and translator.

Yu met some of the influential thinkers of the day, as Dr. Sung-bum Yoon, a leader in Korean theology, and Dr. Dae-sun Park, a brave scholar who criticized South Korea’s military dictatorship. Yu himself faced government censorship and witnessed student and civilian protests.

During Yu’s life, there were many influential movements for reunification. The high point for him was when President Dae Jung Kim walked cross the DMZ to embrace his northern counterpart, Jung Il Kim. Koreans everywhere held their breath. The moment didn’t last, but many took heart at the thawing of tensions between the two states.

In 2004, the North Korean leadership consented to a program that would allow South Korean families to meet their North Korean family members in a supervised event. After decades of separation, Yu and others reunited with their Northern family members. Yu describes his initial fears, the awkwardness, searching the faces that had been changed by years, and the joy of renewing family ties. Yu was allowed several trips. During one of the visits, with great caution, he performed a secret worship service for his sisters, reading from Jeremiah 29:4-7, a passage about thriving in exile.

Yu also describes his life partner, Yon Sil, who he met during university. They married, had children, and traveled for the ministry through Asia, Europe and America. He describes his marriage that spanned decades. In later years, Yu dealt with his wife’s dementia as a loving and devoted caregiver.

The memoir is an engaging narrative of that describes a time, geography, and the many players who enter and leave one’s life. Yu is a detailed storyteller of events and people. The photos of his family and kin greatly add to his storytelling. This memoir is an engaging record of the history of one Korean family. Despite Korea’s fractured history, and the years of hardship for the nation and the people, Yu is never accusatory or judgmental. Despite the historical and social traumas that assaulted a nation and its people, Yu focuses on faith and family as the keys to surviving and thriving.

Yu, who was born during the Japanese colonial occupation, has lived through some of the most turbulent years of modern Korean history. He is a retired minister of the United Methodist Church, and holds several academic degrees in Korea and the U.S. He has published his own works and translated others from English to Korean. During his career, he served in American, Canadian, and Korean congregations. His memoir is appropriate for any reader interested in Korean War history, the Korean diaspora and the resilience of family.