Some thoughts on the new dark reality for immigrant communities | By Chen Zhou (Winter 2026)

Two Fridays ago, my wife and I made a decision we never imagined making in America: Wherever we go, we would carry our U.S. passports.

Not because it’s normal.

Not because it’s required.

But because it feels safer.

Around the same time, many lawyers began offering unsettling advice to U.S. citizens, such as “Say less,” “Follow instructions,” “Don’t argue”. Not because the law demands it, but because a new reality does.

That was the moment it became clear to me: Something fundamental is shifting.

Why Minnesota?

People across the state are asking the same question. Why Minnesota? Why such a heavy presence of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and other federal immigration enforcement here? Are we afraid of undocumented immigrants crossing from Canada?

The answer does not lie in the immigration numbers. Minnesota does not have the highest number of undocumented immigrants. There are lots of estimates on percentages of immigrant population per state. The top five are usually named as California, followed by New Jersey, New York, Florida and Nevada. California is at about 27 percent immigrant population; Nevada at about 20 percent. Minnesota is way down the list, at about eight percent.

But it does have one of the highest per-capita concentrations of ICE agents in the nation right now, and the Twin Cities is the main target. No wonder the key question in all our minds is “So why us?”

The more I thought about it, the more it made sense. Minnesota was perhaps thought to be a “soft target” — geographically isolated, culturally polite, with enough first-generation immigrants who tend to keep their heads down. Big cities hold assets. Red states have loyal bases. Places like ours are easier for the federal government to target its military power.

Or so they thought. During January 2026, however, Minnesotans showed how this theory was wrong. Instead of caving under the onslaught of armed thugs, they have put up a persistent and resilient target, repelling ICE troops with righteous anger, unity, self-control and even humor, despite unlawful and often brutal ICE behavior.

Fear in immigrant communities

In my community, many people are first-generation immigrants. Their English is accented or limited. They are unfamiliar with American legal culture. They hesitate. They respond slowly. They are not confident, and that makes them vulnerable.

Many are U.S. citizens or legal residents, yet, like people in all non-white immigrant groups, they fear being mistaken for undocumented immigrants. They are not afraid because they have broken the law — but because they believe enforcement will act illegally.

This fear is not abstract. It is real. The proof is on the ground, and it shapes how people speak, move and live.

The cost of standing up

I’ll be honest, I’m not brave. I’m not like Alex Pretti.

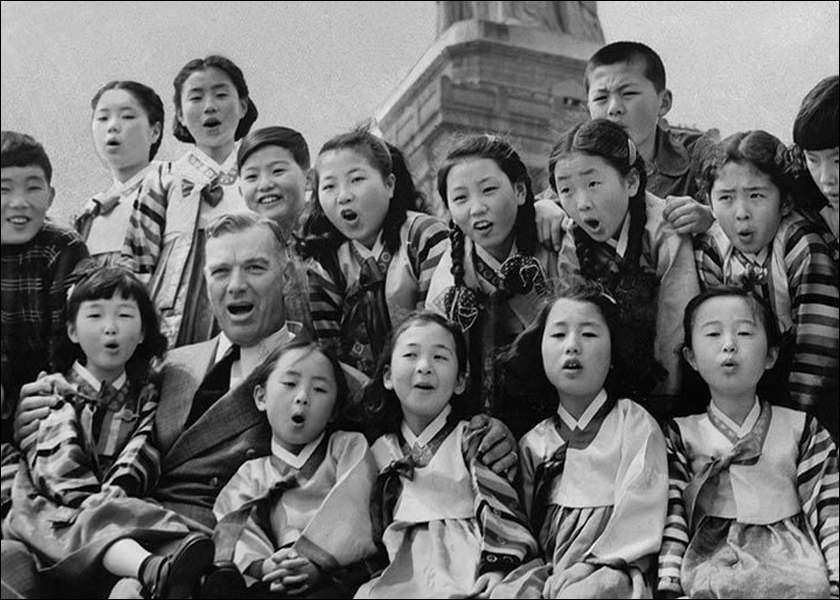

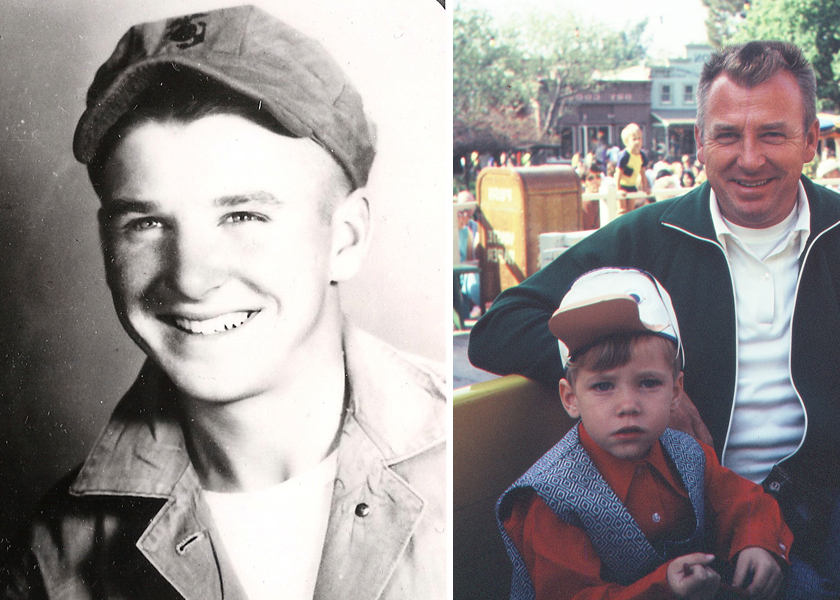

Knowing the risks, he still stood up when he believed the government was acting unjustly. We soon learned that dedication to the public good, and his belief in the ideals of this country played out in his life. He was a U.S. veteran, and became a registered nurse in order to work on behalf of other veterans at the Veterans’ Administration hospital.

In his final moments, he wasn’t thinking about himself — he was trying to protect others. His last words were to ask the woman he was trying to shield from ICE attack “Are you OK?”

“Give me liberty, or give me death” is an American ideal attributed to founding father Patrick Henry in exhorting Virginians to rise up against British rule in 1775. Although all of us, even Alex Pretti, would prefer to show our support for our democracy without being shot dead for it, we can all agree with Patrick Henry that a life spent hiding out of fear of an oppressive and reckless military force is no way to live.

Alex Pretti didn’t get up that morning thinking “Give me liberty or give me death,” but because he was out there, standing up for liberty and helping his neighbors, he was forced to carry it to its brutal conclusion.

He was exercising the most basic constitutional rights: freedom of speech, assembly, petition, and the right to observe authority. For that, he was shot

The American system on trial

On January 7, Minnesota lost Renee Good. The Bad and the Ugly then showed up.

Then on January 24, Minnesota lost Alex Pretti. This time, more Minnesotans stood up. Vast marching crowds, videoed by drones, appeared on social media immediately. The images encouraged Minnesotans and all Americans that we stand together in defiance, resilience, courage, and most of all, unity. These images were proof that there would be no backing down in the face of tyranny.

The U.S. was first called the “Great Experiment” by George Washington. At the time of its founding, the U.S. governance structure was unique. Its original genius was not to confer power only to perfect leaders, but to allow a system designed to restrain power. The three branches of government are designed as co-equal so they can tug one another toward a dynamic middle. Separation of powers, due process, and public accountability were meant to prevent exactly the kind of abuse we are all witnessing in this moment.

America’s strength is not that it never errs. It is that it can correct itself. Recently, that self-correction design has been corrupted and skewed. It is a time where the experiment is being tested. Will it hit a breaking point?

What patriotism really means

Recent events have caused me to reflect about what American patriotism is. For me, it is an act: Patriotism means upholding the democratic ideals the country was built upon. It is also a feeling of loyalty to democratic principles and norms: Liberty, justice, and the rule of law.

Citizens in a democracy are not subject of a greater power; they are overseers of a system derived from their own power.

Conflict is not a failure of democracy — it is evidence that democracy still functions. There are accepted principles around government-sanctioned conflict. The media can question the government. Citizens can question law enforcement, including ICE.

I am stating these principles advisedly, since many citizens have been violently dragged from their cars and detained for taking photos or filming on their cell phones. Recently, two Black journalists were arrested (then released) for reporting on a protest held at a St. Paul church.

And, of course, Alex Pretti and Renee Good were killed by federal immigration authorities for showing up and questioning ICE. As history reflects on this moment, I believe they will be remembered for speaking up, protecting others, and in holding power accountable. To many, those actions reflect the very spirit of patriotism — ordinary citizens standing for what they believe is right.

Now, across the country, Americans of many political views are asking the same question: Are we abandoning the Constitution itself?

A brief reminder on the Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is a set of 10 amendments to the Constitution. They were intended to guarantee the rights of individuals, check and restrain the power of the government. A few of these amendments are particularly important in this moment:

• First Amendment: The right to speak, freedom of the press, the right of assembly, and petition the government for grievances against it without fear of death.

• Second Amendment: The right to keep and bear arms (as a safeguard against tyranny, not a pastime).

• Fourth Amendment: No searches or seizures of a person’s home or private property without probable cause and a warrant.

• Fifth Amendment: Every person accused of a crime has the right to due process, that is, there is no imprisonment without fair procedures and trials.

• Sixth Amendment: The right to a speedy and public trial by jury in criminal cases, for specific criminal charges. The accused must be able to formally face the accuser, present their own witnesses, and be represented by a lawyer.

How many of these rights are now being violated by ICE? ICE’s oppressions are challenging our First Amendment rights to speak and assemble, and the recent arrests of journalists (for showing up and doing their jobs) are obvious attempts to chill the freedom of the press.

Alex Pretti’s Second Amendment right to bear arms was certainly questioned in the aftermath of his death by the federal authorities.

ICE is also battering down the doors of private homes to arrest and take away the occupants, and dragging people out of their cars, violating their Fourth Amendment rights to unreasonable search and seizure of one’s home and personal property.

Detainees are being flown to holding facilities out of state and often denied representation either because their attorney is denied access or because the attorney cannot even find out where they are, thus violating their Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights.

Demonstrators have also been arrested and taken away under no particular charge, for being too annoying or challenging to ICE authorities, for refusing to follow ICE orders they consider illegal, and/or for looking like an immigrant (i.e., a person of color).

Immigrant detainees and arrested demonstrators are both being denied their Sixth Amendment right, when arrested, to have specific charges against them, with the opportunity to refute the charges in court. This puts them in the untenable position of not knowing how to defend themselves because they don’t know what they are accused of.

How many of our individual rights have to be taken away before we say ”No more”?

A question of decency

Most Americans are decent people. Which makes an old question echo loudly again: “Have you no sense decency, sir?” This was asked of Senator Joseph McCarthy in 1954 during proceedings of his House Un-American Activities Committee to upon McCarthy’s harsh accusations that one of attorney Joseph Welch’s staff had ties to a communist organization.

McCarthy’s anti-communist campaign was a personal vendetta to root out suspected “communists” in the U.S. government, along with any LGBTQ-plus government workers or officials, who were labeled as security threats. Its few Democratic members resigned in disgust early on, but hearings rambled on, televised, for months in 1954.

The question about decency reverberated with viewers, ordinary Americans were tired and revolted by his campaign. After that pointed question, McCarthy’s power disintegrated almost overnight. There are many current parallels to this moment of history today.

It was a watershed moment. Have we also just experienced another such reverberating moment?

Blaming the victim

Upon hearing of Pretti’s death, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem was quick to describe his actions as “domestic terrorism,” saying Pretti was “attacking” officers and “brandishing” a weapon before he was killed. Other loyal Trump administration staff joined in on the blame.

Right after that announcement, of course, they were walking those comments back, because the video recording, taken by a brave (and law-abiding) bystander, clearly showed what happened. We all saw the video, we know the facts, and we will NOT agree to conclusion that the murders’ higher-ups decided to force-feed to the public. ( “Have you no sense of decency?”) The eyewitness testimony and many videos especially contradict Noem’s accusation about the legally-carried gun, which he never drew.

What we can do

In the Chinese American community, many are choosing caution. Safety comes first — protecting family, avoiding unnecessary risk. As immigrants, many of us try to avoid trouble. We focus our energy on protecting and providing for our families — staying safe, staying quiet, and keeping away from conflict.

But there is more we can do even if we cannot or should not be marching in the streets right now. Personally, I have decided to:

- Thank neighbors who protest when others are afraid.

- Record events peacefully and lawfully — documentation matters.

- Support community business, particularly minority-owned and immigrant businesses, some of which have to close intermittently for fear of ICE raids.

- Participate in community event such as a Lunar New Year celebration or any other event where the space is safe.

Most importantly, Asian Americans must not live in fear. This is a time to believe in the ongoing experiment of America, and remind ourselves that patriotism is an ongoing act. Our great experiment needs our support to succeed.

In the words of Alex Pretti, at a remembrance of a patient who had just died at the Veterans’ Administration Hospital, “Today, we remember that freedom is not free. We have to work at it, nurture it, protect it, and even sacrifice for it.”

And for my fellow Minnesotans coping with a disrupted life in their home cities, we need to persevere. Our community needs its liberty back, and we can all help achieve it.