A pardon campaign targets two transnational adoptees aging without retirement benefits | By Martha Vickery (Winter 2024)

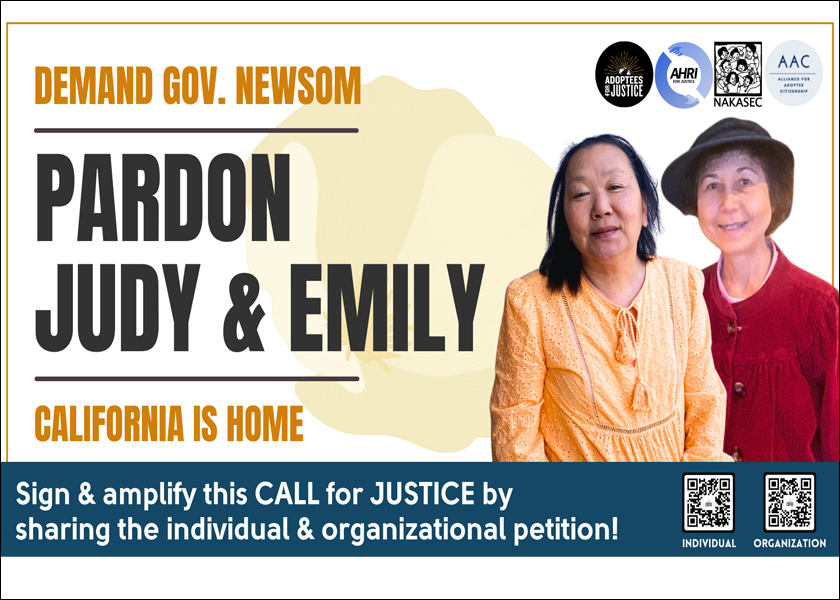

A service and advocacy organization for transnational adoptees is building support for two adoptees from California who need a governor’s pardon in order to apply for citizenship and qualify for important health and monetary benefits they need as retirees. The Adoptees for Justice (A4J) organization is gaining support for the pardon from individuals and organizations within California and in other states as well, with a goal to secure the pardon from Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2024.

A comprehensive bill to convey citizenship to all transnational adoptees has been introduced, rewritten and reintroduced in Congress numerous times for more than 10 years. With lobbying support from its champion organization A4J last year, the Adoptee Citizenship Act got very close to being law. It was successfully added to an omnibus bill during last year’s Congress, but was stripped from that bill late in the session.

Absent that key bill becoming law, transnational adoptees who were not made citizens as children, need to obtain citizenship as adults through other means. Until recent years, citizenship was a separate court process from adoption, and sometimes parents/guardians did not take this step. They may have been ignorant of the law, or may have failed to go through the citizenship step for some other reason. It is estimated that many thousands of international adoptees are without citizenship. A large group of these adoptees are now becoming senior citizens.

The two transnational adoptees who are subjects of the current pardon campaign by A4J are both in their 60s, and both have convictions for minor crimes in their past. That makes their need for citizenship both time-sensitive and procedurally difficult. Both women have been active in the citizenship campaign of A4J for many years; A4J recognizes that their work on behalf of fellow adoptees was part of choosing them as the recipients of this advocacy.

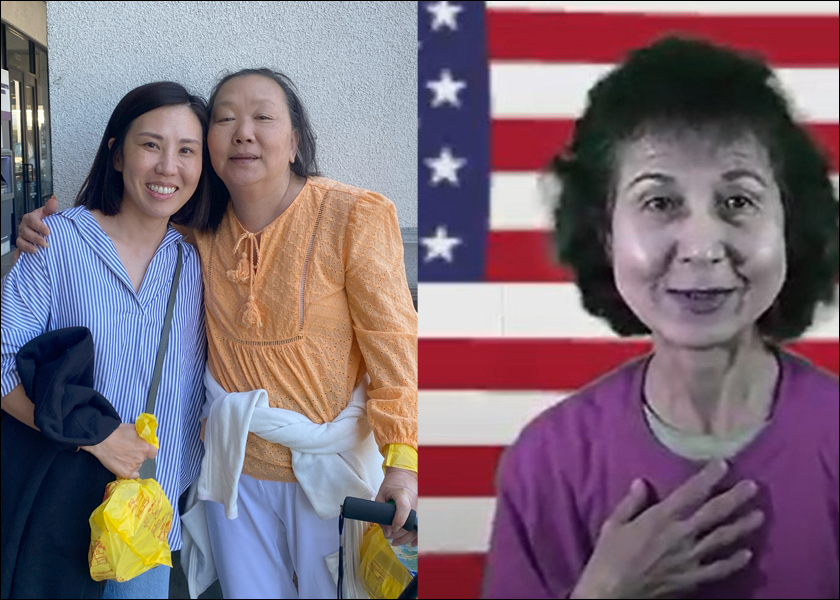

The Pardon Judy and Emily Campaign on behalf of Korean American Emily Warnecke and Taiwanese American Judy Van Arsdale is one of the recent efforts in a broad campaign to keep the citizenship campaign for adoptees in the public mind. The Korean American Service and Education Consortium (NAKASEC) through A4J, its branch organization, has been promoting the pardon campaign with the public.

The pardon campaign includes a petition for individuals and a sign-on letter for organizations (see links in note at end). According to Mary Angilly, a consultant working with A4J, the project is California-specific but A4J organizers want to get groups from many states to sign onto the letter. Similarly, the petition circulating online to encourage Gov. Newsom to pardon Warnecke and Van Arsdale can also be signed by non-Californians.

Angilly said that the group organized some days of advocacy in Washington, DC during October, and has been working with members of Congress to try to get new co-sponsors for the bill, concentrating particularly on potential Republican co-sponsors, since it is intended as a bipartisan bill. A4J’s goal is a comprehensive bill that will include all transnational adoptees, including those who have been deported to their country of origin. This would allow deportees can return to the U.S. and live as citizens.

Jenny Seon, an attorney and an immigration law expert working with Ahri Center, a southern California legal aid and advocacy organization specializing in immigration, has been planning the legal strategy for the pardon campaign.

Seon has been working with A4J since about 2013. Back then, she explained, she was working on immigration law with a different organization. When she transitioned to the Ahri Center, she brought transnational adoptee clients with her, and continued to take on more adoptee clients with immigration challenges. Working with adoptees often includes researching and discovering that person’s entire immigration history, she said, since many immigrated too young to remember anything about it, and may not have understood their legal predicament as non-citizens until they reached adulthood.

The need for the official pardon is because both VanArsdale and Warnecke have past criminal convictions for some minor crimes, Seon explained. The convictions were resolved more than 10 or 15 years ago. “However, for immigration law, those crimes still stand, and they will block any attempt to get citizenship,” she said. “For immigration purposes, the law looks at it differently. Even though all those years have passed, it won’t matter. For Judy, even applying for citizenship could trigger deportation.”

Obviously, Seon said, they are not going to risk triggering a deportation. “The only alternative really is to ask the governor for a pardon,” she said since official pardons by state governors are acceptable documentation for the immigration authority.

Beyond the inability to vote and participate in civic life, not having citizenship carries a lot of serious negative consequences for non-citizen adoptees, particularly as they get older and need to retire. Warneke and Van Arsdale both need the basic benefits of Social Security retirement income and Medicare health insurance coverage, and they need them soon, Seon explained, since both are at retirement age, and both have significant health problems.

Emily’s story

Warnecke said she worked for many years in a career as an inspector in the California aerospace industry, ensuring that precision parts and tools were produced to the correct standards for industry or the military. She learned on the job, becoming certified in various inspection and tool-calibration skills, and rising in the field to a high level of certification. Warnecke has been divorced for many years after an abusive marriage and has a 43-year-old son.

According to Seon, Warnecke’s case is not a typical one. Her adoption was processed in Tokyo, and the paperwork was lost. Her parents never made her a citizen, believing that her adoption made it automatic. This situation, compounded by the criminal conviction, triggered the U.S. government to begin deportation proceedings for her some years ago. Due to the unusual routing of her adoption through Japan, South Korea had no record she had ever been a citizen. South Korean authorities refused to accept Warnecke as a deportee, Seon explained, and her case remains in limbo. She has to check in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) annually, Seon said. Her legal status is uncertain.

Warnecke now lives with a condition that makes it painful for her to walk or sit. She uses a walker or a wheelchair to get around. “My goal was to continue to work in aerospace and get my pension and retire,” she said. The degenerative disk condition in her spine got steadily worse in her 50s, and finally her doctor told her she should not attempt to go back to work. Initially, she qualified for a state disability support program which had limited funding, and eventually her funding for that ran out.

Subsequently, she applied for Social Security and was turned down. Her goal for getting citizenship is primarily to access full disability benefits, which will provide the most support for her as she ages. After she was turned down for Social Security, she was referred to A4J by a legal advocacy organization she had contacted. She has been working with A4J and NAKASEC as an advocate since about 2016, she said.

Judy’s story

Born in Taiwan, Van Arsdale was the oldest of eight children of a single mother. When she was a child, the Pearl S. Buck Foundation was working in Taiwan to sponsor Amerasian children (a term used at that time); staff found the children by going door-to-door and asking people about the location of any children whose fathers were American, Van Arsdale explained. She remembers two staff members from the foundation meeting her after school one day and walking home with her. After talking to her parents about the foundation’s sponsorship program “they signed me up and we got $10 a month. That helped a lot, because that was half of my dad’s salary,” Van Arsdale recalled.

A life-changing event for her happened at age 12, she said, when she needed an emergency appendectomy. Her adoptive father-to-be was the surgeon who worked at the nearby Christian Science Church-sponsored hospital. Her mother talked to the surgeon after the surgery, and eventually found out that he and his wife were interested in adoption. Her parents and the doctor and wife agreed on the adoption. At that time, the Pearl Buck Foundation was also facilitating intercountry adoptions for Amerasian kids as well, according to Van Arsdale. She lived another four years in Taiwan with her adoptive parents before immigrating to the U.S.

Van Arsdale left her adoptive home in California at age 17; it was precipitated by her adoptive mother’s abuse. As a young adult, she served time for a minor crime. Her struggle was exacerbated by being young, poor and having no support network; she was represented only by a public defender. Van Arsdale said she remembers contacting the public defender attorney several times while in prison to alert him that her permanent residency (green) card and Social Security card had been confiscated by prison staff, and to ask him to retrieve them. She later found out they had been lost. Her criminal record has also made it complicated to obtain replacement copies of those two ID cards, which are crucial for accessing Social Security retirement support and Medicare benefits. She is now age 65.

As an adult, Van Arsdale pursued a career as a registered nurse. At one point, a patient filed a minor complaint against her, which resulted in an automatic background check. When she filled out the information for her original license, she said, she did not add her long-ago criminal conviction to her background, fearing repercussions. The required background check brought it to light. Thereafter, her license was put on probation, which made it nearly impossible to get another job as an R.N., she explained. The situation led to a continuing struggle with poverty and housing insecurity.

Van Arsdale, a founding member of Adoptees for Justice and an activist for adoptee citizenship for the last eight years, explained that her adoption was done in Taiwan while her adoptive parents still lived there. In searching for her paperwork many years later, Van Arsdale said, she found out that the Pearl S. Buck Foundation’s Welcome House, located in Taiwan until 2015, had been closed, and she was told that records stored there had been destroyed. There are no copies of her paperwork in the U.S., she said.

Living in limbo

Like Warnecke, Van Arsdale was always reassured by her parents that her citizenship was automatic because she was adopted. Since discovering she is not a citizen, she has heard many stories from other transnational adoptees about how their adoptive parents were given conflicting and wrong information about their children’s citizenship by authorities. Van Arsdale reasons that there was a poor understanding at that time about adoptees’ citizenship status because transnational adoption was still so new.

Personally, Van Arsdale said, getting a pardon and then citizenship, “would open up a new world for me. It would be a transformative process. It signifies a commitment by the government to justice and compassion for adoptees like myself.”

Aside from that, there are many practical concerns that citizenship would solve for her. “The Social Security which I paid into while I worked for almost 30 years – I can’t access it. It is crucial for my financial stability and well being.” The same goes for Medicare, which she was also denied. Citizenship would also give her opportunities for better job opportunities, as well as civic privileges.

During this time of being in limbo for deportation, Warnecke said she has thought a lot about non-citizen transracial deportees. “There are so many who have been deported. Their stories are sad. Even if I get my citizenship I will not stop fighting for adoptees and for DACA,” she said, referring to the limbo of immigrants brought into the country as children, and never made citizens, and the Obama-era program known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) which was invented as a stopgap to avoid deportation of young adult immigrants who had always lived in the U.S.

Warnecke said she has personally spoken to members of Congress about the A4J bill, and has been successful in getting new co-sponsors signed on. She has discussed with elected officials the case of Phillip Clay, a Korean American adoptee who committed suicide in South Korea after being deported due to being a non-citizen and having a criminal conviction.

Warnecke said that Jenny Seon from Ahri Center, Becky Belcore from NAKASEC and other Korean Americans, some of whom are adoptees, have helped her even though they have citizenship. She said she is committed to advocating for non-citizen adoptees struggling with citizenship whether or not she achieves her own citizenship.

In the spring, A4J will also mount a campaign to persuade the governor to grant the pardon. It has been a slow and steady process since fall 2023 to raise awareness about adoptees whose path to citizenship is difficult because of missing documentation, a criminal conviction, or both. Gov. Newsom could shorten the journey with the stroke of a pen, and transnational adoptees with their supporters will be pushing for that support in the months to come.

Editor’s note: A4J is urging individuals and organizations to support this petition, and to support the Adoptee Citizenship Act. The A4J petition asking Gov. Newsom to grant the pardon, is at this link. The sign-on letter for organizations to support the Pardon Judy and Emily Campaign is at this link.