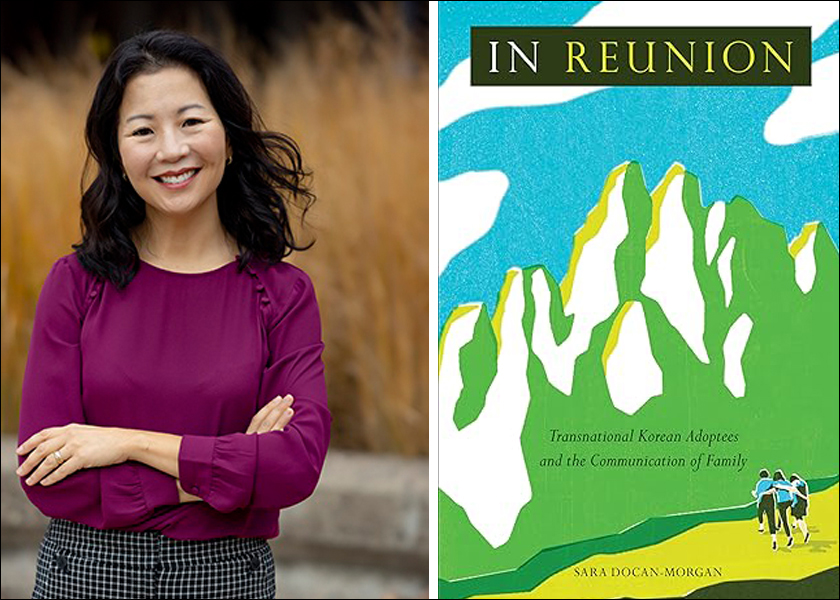

In Reunion: Transnational Korean Adoptees and the Communication of Family ~ By Sara Docan-Morgan

(Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2024, ISBN #978-1-4399-2283-5)

Review by Alice Stephens (Spring 2024)

All human relations require some kind of communication, and communication is integral to the family unit. When the adopted child enters a new family, they take on the cultural characteristics of that family, regardless of their ethnicity or country of origin. If the adopted person then reunites with their first family, they must learn how to bridge the years of separation.

This fraught process becomes much more complicated when the person has been adopted from abroad. Sara Docan-Morgan, a professor of communication studies and a Korean adoptee in reunion, examines how Korean adoptees and their birth families navigate reunions, and the communications issues involved, in the extensive new study In Reunion: Transnational Korean Adoptees and the Communication of Family.

Though the focus of Docan-Morgan’s book is how communication affects reunion, In Reunion serves as an excellent primer on Korean adoption, from its origins as a way to “rescue” war orphans and mixed-race children, to the Korean government’s reliance on it as a substitute for a social safety net and an effective way to raise money for depleted post-war coffers, to its global reach and sociological effect on adoptees and their families, both Korean and adoptive.

By introducing the chapters with personal testimony of her own reunion story, Docan-Morgan adds a relatable tone to In Reunion that elevates it beyond an academic text, making it accessible to interested readers. The author is explicit about how, when, and from whom she gathered her data, including a handy table of participants, fourteen adopted to America and four to Denmark, even providing the questions that she asked in two interviews conducted 10 years apart. The author’s stated goal “is to understand, examine, and illuminate the experiences of transnational Korean adoptees in reunion… [and] draw special attention to the role of cultural and language differences in the development and maintenance of relationships between transnational adoptees and birth families.”

Delving into why adoptees seek out their original families, the author points out that even within the same adoptive family, one sibling may choose to search while another chooses not to. Some have the blessing and participation of their adoptive parents, including five whose parents initiated the search while the adoptees were minors, while others did not involve their adoptive families. The author writes, “[R]eunions occur through a series of incremental decisions.” The adoptee must initially decide to search, then whether to meet the family, and finally whether to maintain a relationship.

Often, the first meeting does not match the adoptee’s expectations. Many report being in shock, disassociating, masking their emotions, and/or reacting with less outward emotion than their birth parents. That introductory meeting is an unsettling initiation into the arduous process of establishing a relationship with one’s closest blood relatives across yawning chasms of culture and language. Along the way, the adoptee must carry the burden of everyone else’s feelings, careful not to seem to be rejecting the family that raised them for the one that birthed them, or favoring natural parents over adoptive ones. Docan-Morgan notes that “letting go of expectations for a specific type of family relationship can create space to build a closer relationship.” The less expectations and more flexibility everyone in reunion has, the better.

But cultural assumptions are hard to overcome, and confusion, hurt feelings, and misunderstandings are inevitable. Some interviewees spoke of not being able to see themselves in their genetic families, while others were put off by birth family members’ direct criticisms about weight, appearance, marital status, and other personal characteristics. Due to patriarchal values, females comprise the majority of Korean adoptees, and many raised in the Western tradition struggled to perform to their birth family’s standards of feminine beauty and behavior.

Some birth parents refused to tell other family members about the adoptee, straining the relationship and causing pain. A few adoptees found contact with siblings or cousins more rewarding than with parents. The author concludes that familiarity with the cultural and historical reasons behind their Korean families’ actions made adoptees more able to accept behavior that might have otherwise offended them.

Not surprisingly, Docan-Morgan found that one of the hardest barriers to overcome was that of language. None of the interviewees retained any of their native language, and most hadn’t studied it before they were reunited. Those who did try to learn Korean found it very difficult, requiring years of dedication to achieve basic conversancy. Respondents in the study also said that few Korean relatives spoke any English. Moreover, some family members expressed disapproval at the lack of the adoptee’s Korean language proficiency, putting the burden of communication entirely on the adoptee without acknowledging their own role in the loss of language.

There is an “emotional weight” to studying Korean, as well, that adoptees may find too heavy to carry. Therefore, it is helpful for interpreters to be present during meetings, though instances where long spoken passages are whittled down in translation to a short sentence or two led to trust issues in the reliability of the translator. In many instances, nonverbal communication becomes crucial to the relationship.

While straddling two countries and languages in their new relationship with birth family, adoptees reported that they must also tend to their adoptive families’ feelings and concerns. Some parents may be excited about their child’s reunion, while others may fear that they will be replaced by the birth parents. Traditionally, adoptive parents have controlled the adoption narrative, celebrating adoption (“Gotcha”) days, emphasizing a “meant to be” bond, promoting the notion of a “forever family.”

Some interviewees felt obliged to reassure their adoptive families that they still reign supreme in the adoptee’s heart, and to withhold their true emotions around reunion. Meetings between the sets of parents can be stressful and awkward as the birth parents express guilt and shame. Many felt a lack of emotional agency, as they were obliged to tend to everyone’s feelings before their own.

Ten years after Docan-Morgan’s initial interviews, she conducted a second interview with 17 of the original participants. In the interval between interviews, new communication technologies had emerged in the form of smartphones, the messaging app KakaoTalk, video chats, translation apps, and social media. While a few had lost touch with their Korean families, most had persisted in the relationship, whether that meant annual visits or an occasional text.

In the intervening years, participants had become more aware of the history and politics of transnational Korean adoption and the larger social forces that shaped their lives. “Whether it was through interacting with other Korean adoptees online or in person, or reading about the topic, interviewees spoke of issues such as deception by orphanages and adoption agencies, ensuing trauma for birth families and adoptees, power discrepancies between women and men in Korea, and the lack of agency for single mothers in Korea.” They accept that there will always be an “adoption information gap” in their stories, as details have been altered by adoption documents, or because birth family members hide facts, or due to knowledge simply lost to the relentless march of time.

Docan-Morgan makes clear that, just as with adoption, reunion is no fairy tale with a happily ever-after ending. She surmises that the most successful reunions are those where the adoptee understands their relationship with their first family “through the lens of Korean culture.” In order to do this, they must adjust their communication techniques to transcend language and enculturated thought systems. The book concludes with recommendations for the adoptee and adoptive parents going into reunion.

By examining Korean transnational adoption through the lens of communication and reunion, Docan-Morgan has written an accessible work of scholarship that will enlighten all readers about the complexities and challenges of transnational adoption.